When it’s time to suspect mastoiditis for patient pain.

HISTORY

A 25 year old male presented with progressive pain and drainage to his right ear over two weeks. The pain became worse with talking, chewing or palpation. He had also noted a subjective fever, chills, anorexia and a decrease in hearing acuity. He denied trauma to the ear, nausea or vomiting, facial asymmetry, voice change or difficulty swallowing.

He had been seen six days prior at an outside hospital for the symptoms and prescribed oral ciprofloxacin, but discontinued it after one day due to side effects. Previous medical history was significant for chronic complicated otitis media and cholesteatoma. He underwent right tympanomastoidectomy and ossicular chain reconstruction as a teen. Past medical history was negative for diabetes or other issues. He smoked one pack per day and denied any drug or significant alcohol use.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On examination, the patient was uncomfortable, but in no acute distress. He was mildly tachycardic, with otherwise normal vital signs. He had mild right-sided facial swelling with protrusion of the pinna and trismus (Figure 1a).

Mucous membranes were dry. Edematous and erythematous with scattered crusted drainage was identified in the right auricle.

The periauricular area was erythematous with a palpable fluid collection superiorly and posteriorly (Figure 1b and 1c).

The right external auditory canal was edematous and occluded by purulent drainage, precluding visualization of the tympanic membrane. Exam on the left ear was normal. Cranial nerves were intact and the neck exam was normal. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

LABORATORY TESTS AND IMAGING

The patient received intravenous fluids and morphine for pain relief and was started on intravenous vancomycin and cefepime due to concern for a mastoid abscess. Complete blood count was significant only for mild leukocytosis, but no left shift or bandemia. Basic metabolic panel was unremarkable. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated to 43 and 3.2 respectively.

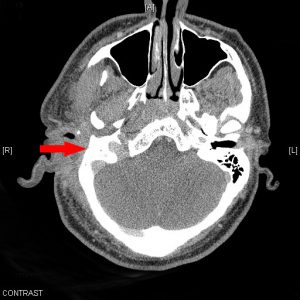

A CT of the temporal bone with contrast was obtained demonstrating severe inflammation of the right middle and external ear extending to the right temporalis region, skull base, parotid and masticator spaces; a large multiloculated fluid collection measuring 3.5×2.5cm in the superior periauricular tissue with extensive surrounding bony destruction involving the right mastoid; and complete obliteration of the middle ear cavity, ossicles, mastoid and petrous air cells with fluid opacification (Figures 2a-2b).

The patient was kept NPO and otolaryngology was consulted, who recommended continuation of IV antibiotics and admission for exam under anesthesia with incision and drainage of the abscess.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of mastoiditis should be clinically suspected in any patient presenting with posterior ear pain, fever, hearing loss, swelling of the pinna, erythema over the mastoid and inferior displacement of the auricle.

Complications of acute otitis media (AOM) occur in less than 0.5% of adults.[2, 4, 5] These complications may lead to significant morbidity because of the proximity of the middle ear and mastoid air cells to the cranial fossa. If inflammation in the mastoid air cells persists, exudate can destroy the bony septae between the air cells and cause coalescent mastoiditis, which in turn may lead to abscess formation. Infection can track inferiorly to the neck; medially to the petrous air cells where it can cause petrositis and facial or abducens nerve palsy; posteriorly where it can cause osteomyelitis of the calvaria; through the oval or round window into the cochlear and vestibular apparatus where it can cause suppurative labyrinthitis; or toward the inner cortical bone where it can cause meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis, or intracranial abscess. [1, 2, 5]

Patients with suspected acute mastoiditis should have a CT scan of the temporal bone and be started on IV antibiotics. Patients presenting with a focal neurological deficit, nausea and vomiting, seizures, persistent cephalgia or severe headache should obtain an MRI to r/o an intracranial complication. In general, patients with mastoiditis should be admitted. In addition, any patient requiring IV antibiotics or surgical intervention requires admission.

MICROBIOLOGY

Infectious causes of AOM are similar in adults and children with Strep pneumoniae and non-typable Haemophilus influenzae being most common. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus and Moraxella catarrhalis are less frequent causes. [2, 3]

Mastoiditis is not well-studied in adults so the exact incidence is unknown, however the most common isolates are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA. Because of this, vancomycin is the antibiotic of choice.

If the patient has received antibiotics recently or has history of recurrent AOM, anitbiotics that are active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa like ceftazidime, cefepime or piperacillin-tazobacyam should be added as well. [2, 3]

OUTCOME OF THE CASE

The patient underwent incision and drainage of right peri-auricular abscess as well as right otomicroscopy with debridement of external auditory canal. Intraoperatively, copious brown purulent drainage was obtained from the abscess with a feculent odor; cultures were obtained and a penrose drain was placed. Extreme edema of the external auditory canal prevented visualization of the tympanic membrane.

Two Oto-wicks instilled with Afrin were placed. He was continued on intravenous vancomycin and cefepime. Cultures grew out Strep viridans. The drain was removed three days later and the patient was discharged on Ciprodex drops and Bactrim for 10 days. He was seen by ENT several weeks later with reported symptomatic and clinical improvement.

REFERENCES

- Anderson KJ. Mastoiditis. Pediatr Rev 2009; 30:233.

- Bluestone CD. Clinical course, complications and sequelae of acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000; 19:S37.

- Celin SE, Bluestone CD, Stephenson J, et al. Bacteriology of acute otitis media in adults. JAMA 1991; 266:2249.

- Hafidh MA, Keogh I, Walsh RM, et al. Otogenic intracranial complications, a 7-year retrospective review. Am J Otolaryngology 2006; 27:390.

- Leskinin K, Jero J. Acute complications of otitis media in adults. Clinical Otolaryngology 2005; 30:511.