You walk into your next code and it’s a man in his 60s who collapsed on his way to his cardiologist’s office. His wife insists that he doesn’t need CPR because he has a kind of artificial heart, an LVAD. No one in the department has ever seen a patient with one of these before.

You walk into your next code and it’s a man in his 60s who collapsed on his way to his cardiologist’s office. His wife insists that he doesn’t need CPR because he has a kind of artificial heart, an LVAD. No one in the department has ever seen a patient with one of these before.

Sharp Memorial’s Dr. Zach Shinar explains how to manage the care of the patient with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD)

You walk into your next code and it’s a man in his 60s who collapsed on his way to his cardiologist’s office. His wife insists that he doesn’t need CPR because he has a kind of artificial heart, an LVAD. No one in the department has ever seen a patient with one of these before.

In our last piece, we covered the first part of an interview with Dr. Zachary Shinar. The cutting edge work being done by Zach and his colleagues at Sharp Memorial Hospital in San Diego has been inspiring to all of us. In our last installment, we talked about ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) in the ED. In this piece we cover LVADs, or left ventricular assist devices, which are implanted via open heart surgery into patients with severe heart failure. It is not surprising that an institution that can support an ECMO program out of its ED will also end up discharging patients from its wards with implanted LVADs. Both are features of the most advanced management of selected patients with advanced coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure.

For me, I will always associate the LVAD with former vice-president Dick Cheney. I remember the television interview that he did in 2010 where he showed the whole nation his LVAD and the extra batteries that he carried in his fishing vest. After almost two years on the LVAD, he received a heart transplant and is doing well.

So, who qualifies for an LVAD? According to Zach, patients must fulfill very specific criteria including severe heart failure (New York classification Stage 4 of 4) with an ejection fraction <25%. Because of the obvious risks of such an expensive and invasive therapy, the potential benefits must outweigh these risks. LVADs may be used as part of a “bridge-to-transplant” strategy – in this case patients also must fulfill additional criteria for heart transplant eligibility. In patients who are not eligible for transplant, such as those with a newly diagnosed malignancy, renal failure or advanced age, an LVAD may still be used as a so-called “destination” therapy.

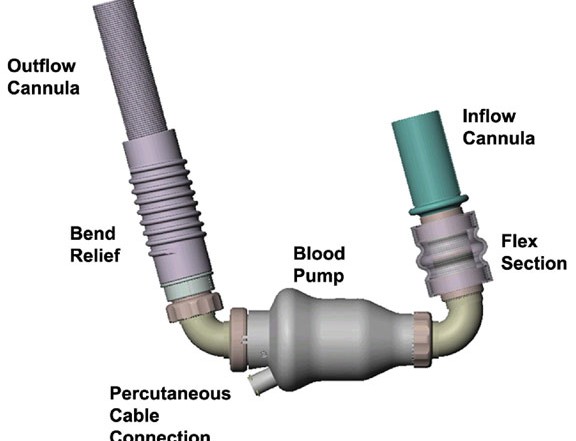

LVADs provide a bypass for a compromised left ventricle. Their intake site is at the apex of the left ventricle and the outflow is into the proximal aorta. LVADs (or RVADs and BiVADs, which assist the right or both ventricles, respectively) are not exactly new. They have been around in some shape or form for at least a couple of decades. But what has changed is that they now provide continuous rather than pulsatile flow. Conceptually, these second generation LVADs cause more trepidation for emergency providers because their recipients may be pulseless, even when they are talking to you!

LVADs provide a bypass for a compromised left ventricle. Their intake site is at the apex of the left ventricle and the outflow is into the proximal aorta. LVADs (or RVADs and BiVADs, which assist the right or both ventricles, respectively) are not exactly new. They have been around in some shape or form for at least a couple of decades. But what has changed is that they now provide continuous rather than pulsatile flow. Conceptually, these second generation LVADs cause more trepidation for emergency providers because their recipients may be pulseless, even when they are talking to you!

So what do you do when a patient with an LVAD arrives in your ED? Well, first off, Zach explains, most presentations actually involve a stable patient. One of the most common problems is a “drive-line infection”, essentially an infection of the power cable that comes out of the body. Although, frank septic shock from these infections is actually uncommon, patients with significant cellulitis around the insertion site may require hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics to cover common skin pathogens.

Bleeding is a big problem in patients with LVADs. In addition to chronic anticoagulant use, which is usually required to prevent clotting in the implanted circuit, patients with LVADs also acquire a bleeding diathesis over time similar to dialysis patients (essentially an acquired von Willebrand’s deficiency). Patients may present with GI hemorrhage, epistaxis or intracranial bleeding. Like all hemorrhaging patients with a coagulopathy, in addition to red cell transfusion, their coagulopathy should be reversed to the extent possible, as soon as possible. In some cases, Zach tells us, they have had to leave LVAD patients on only aspirin because of repeated life-threatening bleeds on coumadin and other agents.

What about the patient in extremis? Well, you can go ahead and check your own pulse first because the LVAD patient usually won’t have one. As Zach explains, one of the first steps in the resuscitation of these patients is to listen to the precordium – not for the presence of an S3 or murmur – but for the mechanical whirring sound of the pump. The algorithm for resuscitation branches at this point.

When the chest is silent (except perhaps the sound of your rescue ventilation), you must search for every conceivable reason for the pump not working – starting with the power supply, cables and battery. Batteries have an indicator that reveals if their charge is low. Most patients will have extra batteries with them or a charging device available.

For patients with a functioning power supply and pump, critical diagnostic steps include placing the patient on a cardiac monitor, obtaining a Doppler blood pressure and bedside echocardiogram.

Defibrillation can still be performed in patients with ventricular dysrhythmias. External chest compressions, however, should be avoided and are a last resort for patients without evidence of perfusion. Conventional CPR may dislodge the LVAD connection from the heart and leave a gaping hole. If compressions are delivered, they should be done abdominally.

Simple ED bedside echocardiography can be instrumental in the LVAD patient with shock. Because most assist devices only help the left ventricle, the right ventricle remains very vulnerable. Moreover, an LVAD device, no matter how effective, cannot draw fluid from the right ventricle through an obstructed pulmonary vasculature. If the right ventricle is larger than the left on bedside echo, right ventricular failure is the most likely culprit.

LVAD patients may suffer a right ventricular myocardial infarction (RVMI); a trip to the catheterization suite is indicated in this scenario and ECG findings consistent with RVMI should be sought. In LVAD patients, increases in pulmonary pressures often result from hypoxemia and acidosis, resulting in RV failure. Thus, every attempt to reverse hypoxemia and acidosis, including early intubation and administration of bicarbonate can be helpful. Lastly, RV failure may be the result of thrombosis in the LVAD system or pulmonary embolism. For this reason, liberal anticoagulation with heparin is advised in the non-bleeding patient.

Dr. Swadron is currently Vice-Chair for Education in the Department of EM at the Los Angeles County/USC Medical Center in Los Angeles. He is an Assoc. Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. EM:RAP (Emergency Medicine: Reviews and Perspectives) is a monthly audio program that can be found at www.emrap.org)

2 Comments

Appreciate this article greatly. I’m trying to understand why bicarbonate was ordered, for my son, prior to placing him on ECMO and Empella, several hours after realizing his B/P had dropped 50/40. He’d received a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy 2016. He’d experienced his 2nd episode of arrhythmia, fainting) 7 months apart, given 5-6 AED shocks in that week said due to low potassium, began complaining about his meds on day 7, in Cardiac Intensive Care, EFR (?) 25 decreased to 5, I’m told and lapsed into unconsciousness by 5:30. Four days later an LVAD was implanted in this 35 yr old. To-date it is not explained the events prompting the extreme emergency measures.

This paper should be removed. In present era, we absolutely do CPR in a LVAD pt. The information on RV failure is not fully correct as written. RVF is a multifactorial issue and in the present era of the full maglev FDA approved device, pump thrombosis is <2%. RVF is driven my natural progression of the cardiomyopathy affecting the RV, aortic insufficiency on LVAD, improper LVAD speed setting and outflow issues, etc.

Please do CPR in a coding VAD pt. Help drive blood through the lungs with compressions so the LVAD and deliver blood systemically…