Exploring ultrasound guided peripheral nerve block in the emergency setting

Introduction:

Phantom limb pain (PLP) is a devastating sequalae of major limb amputation affecting 50% to 85% of traumatic amputation patients. Patients describe PLP intractable pain perceived as originating from the missing limb. There is no optimal pharmacologic management of PLP and many medications that are currently used have substantial, limiting side effects.[[i],[ii]]

Ultrasound guided 6-day, continuous peripheral nerve block (UGNB) has been previously demonstrated to improve outcomes for patients with persistent PLP at 12 weeks post-amputation.[[iii],[iv]] A single shot injection has also been described as an effective long-term solution for PLP.[[v]] However, its use in the emergency department to manage post-traumatic amputation PLP has not been described.

Case Report:

A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department following a high-speed motorcycle collision. The patient was ejected from his motorcycle and experienced a traumatic left arm amputation at the level of the proximal to mid humerus as well as open fractures of his left lower leg. The patient arrived intubated and sedated. His left brachial artery had been previously sutured at an outside institution.

Due to muscular/neurovascular compromise and wound contamination, the left upper extremity was deemed unsalvageable, and the decision was made to revise the amputation with concurrent I&D and wound vac placement.

The patient’s pain was initially described as well controlled with a multi-drug regimen including acetaminophen (1000mg q8h), acetaminophen/hydrocodone (5/7.5 q4h prn moderate-severe pain), hydromorphone (0.2mgs q4h for breakthrough pain), gabapentin (300 mgs q8h), lidocaine (patch q12h) and methocarbamol (1000mg q8h).

However, on post-amputation Day 4, the patient complained of 8/10 LUE PLP according to the morning occupational therapy note. The patient described the pain as an intermittent burning sensation in the missing hand.

On Day 5, the patient’s pain was reported as 10/10 in a trauma surgery progress note. Ultrasound fellowship trained faculty routinely perform nerve blocks in the Emergency Department (ED) and the trauma team requested a block be performed on this patient.

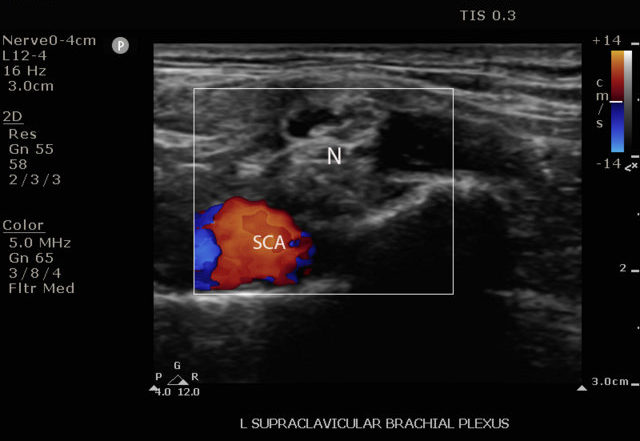

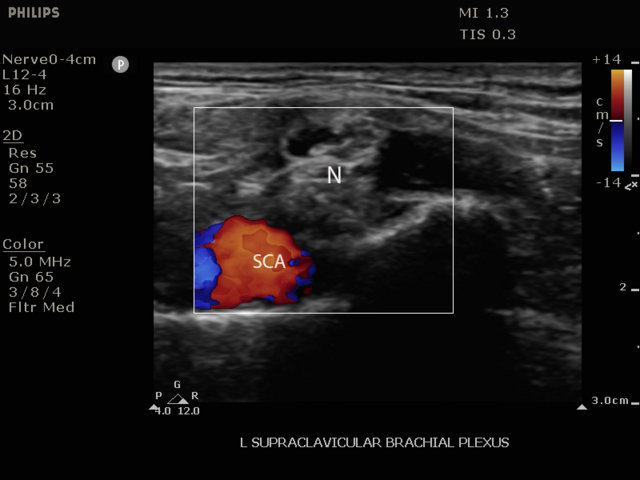

An US guided-supraclavicular block with 30 cc of 0.2% ropivacaine was performed at bedside (figures1-2).

Ultrasound image of the left supraclavicular brachial plexus identifying the appropriate location for the distribution of the nerve block; SCA Subclavian artery; N: neurovascular bundle

A continuous infusion catheter was not placed as at this time, as all blocks performed by ED staff were single shot injections.

On Day 6, the patient reported that the nerve block had provided complete resolution of PLP for about 1.5 hrs, but then the pain returned. Although the patient stated that the returned PLP was no different from what he had experienced pre-nerve block, he reported a reduced score of 4/10 LUE PLP that was recorded in the morning occupational therapy note.

Additionally, the nursing staff reported the patient requesting fewer breakthrough pain medications in the 20 hours post-nerve block. The patient also stated that only the nerve block and the hydromorphone had given him any relief from the PLP.

On the evening of Day 11, the patient reported inability to sleep due to PLP in spite of his medication regimen. A repeat block was requested and was performed using the same technique and medication. In the morning, the patient reported that he had been able to sleep for five hours straight, and the pain only began to return upon wakening.

Discussion

Use of UGNB has been established as an effective means of post-surgical and emergency department acute pain control associated with decreased length of stay and decreased overall opioid use.[[vi],[vii],[viii],[ix],[x],[xi]] The American College of Emergency Physicians now considers UGNB a critical component of pain management in the ED.[[xii]]

Significantly less well established is the use of UGNB as a means to treat or prevent PLP in the emergency setting. To our knowledge, the only clinical trials and case reports that have attempted to use UGNB to treat traumatic PLP are in settings many weeks out from the initial injury.[3,4,5]

In this case report, we describe single-shot UGNB as an effective means for short term phantom limb pain unresponsive to more conservative management approaches in the days immediately following a traumatic amputation.

This success provides a strong rationale for future research on this topic. Particularly warranted would be an investigation into if early peripheral nerve blockade could be effective for preventing or reducing PLP. through a single-shot administration, or continuous infusion UGNB were performed within the immediate post-injury period. Areas to explore could include increasing the concentration of ropivacaine, use of alternate anesthetics or adding adjuvants such as dexamethasone, NMDA-antagonists, cholinesterase inhibitors, epinephrine, and sodium bicarbonate to potentiate the block’s effects.[[xiii],[xiv]]

Conclusions

In the setting of traumatic amputation in the emergency department, UGNB may be an effective tool for treating the acute presentation of phantom limb pain unresponsive to conservative means of pain control.

Additionally, future research is needed to understand if this approach may be able to prevent the initial development of PLP.

[i] Alviar, M. J. M., et al. (2016). “Pharmacologic interventions for treating phantom limb pain.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(10).

[ii] Erlenwein, J., et al. (2021). “Clinical updates on phantom limb pain.” Pain reports 6(1).

[iii] Ilfeld, B. M., et al. (2021). “Ambulatory continuous peripheral nerve blocks to treat postamputation phantom limb pain: a multicenter, randomized, quadruple-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial.” Pain 162(3): 938-955.

[iv] Ilfeld, B. M., et al. (2021). “Immediate effects of a continuous peripheral nerve block on Postamputation phantom and residual limb pain: secondary outcomes from a multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial.” Anesthesia & Analgesia 133(4): 1019-1027.

[v] Sales, F., et al. (2022). B403 Peripheral nerve block for phantom limb pain–more than a temporary fix, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

[vi] Hwang, E. and Y. Lee Effectiveness of intercostal nerve block for management of pain in rib fracture patients. J Exerc Rehabil. 2014; 10 (4): 241-4.

[vii] Neubrand, T. L., et al. (2014). “Fascia iliaca compartment nerve block versus systemic pain control for acute femur fractures in the pediatric emergency department.” Pediatric Emergency Care 30(7): 469-473.

[viii] Mangram, A. J., et al. (2015). “Geriatric trauma G-60 falls with hip fractures: a pilot study of acute pain management using femoral nerve fascia iliac blocks.” Journal of trauma and acute care surgery 79(6): 1067-1072.

[ix] Cogan, C. J. and U. Kandemir (2020). “Role of peripheral nerve block in pain control for the management of acute traumatic orthopedic injuries in the emergency department: diagnosis-based treatment guidelines.” Injury 51(7): 1422-1425.

[x] Kang, C., et al. (2021). “Clinical analyses of ultrasound-guided nerve block in lower-extremity surgery: a retrospective study.” Journal of Orthopedic Surgery 29(1): 2309499021989102.

[xi] Morrison, R. S., et al. (2016). “Regional nerve blocks improve pain and functional outcomes in hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64(12): 2433-2439.

[xii] Care, H.-T. E. C. and U.-G. N. Blocks (2021). “Policy Statements.” Ann Emerg Med 78: e37-e57.

[xiii] Xuan, C., et al. (2021). “The facilitatory effects of adjuvant pharmaceutics to prolong the duration of local anesthetic for peripheral nerve block: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.” Anesthesia & Analgesia 133(3): 620-629.

[xiv] Edinoff, A. N., et al. (2021). “Adjuvant drugs for peripheral nerve blocks: The role of NMDA antagonists, neostigmine, epinephrine, and sodium bicarbonate.” Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine 11(3).