“You won’t believe this, but we just delivered triplets from a 54-year-old woman in the ambulance bay!” you hear your colleague brag. Not to be outdone, your other colleague immediately retorts, “That’s pretty cool, but I just performed an escharotomy on a patient coding in the CT scanner while you were out there mucking around.” Although you are amazed at both stories, you can’t help but raise an eyebrow in suspicion.

You turn to your resident and ask, “What do you think? Big fish or tall tale?”

“Um, tall fish?”, your resident replies without missing a beat. You chuckle as you ask him to tell you about the patient he just finished examining.

“The patient in bed 22 is an otherwise healthy 30-year-old gentleman with a sore throat and muffled voice. He was here a week ago and was diagnosed with pharyngitis. He was discharged home with prednisone and clindamycin, but he says his pain is getting worse. He looks uncomfortable, but is not having any issues protecting his airway right now.”

You start walking over to the patient’s room so that you can ensure that you lay eyes on what could potentially be a catastrophic airway situation. Fortunately, your resident’s clinical acumen was spot on, and the patient is sitting upright in bed, spitting his secretions casually into an emesis basin.

“His vital signs are OK other than a heart rate at 118 bpm, and his physical exam is non-focal other than some swollen, mobile cervical lymph nodes and a really red oropharynx.” Your resident continues: “I tried looking into his mouth with a tongue depressor, but his trismus is preventing me from getting a great view.”

Together you review the patient’s visit notes from a week ago and see that your colleague did everything by the textbook. She obtained a rapid strep that was negative, drew some blood work that were unremarkable, obtained a CT scan of his oropharynx that showed no discernable fluid collections, and provided the patient with IVFs, pain control, appropriate prescriptions, and specific follow up and return instructions. As directed, the patient returned because his symptoms did not improve.

You have your resident grab the ultrasound machine while you make your way around the department to gather some creative essential equipment: an 18-gauge spinal needle, a 3 mL syringe, a laryngoscope and Mac 3 blade, and a cup of ice water with a straw.

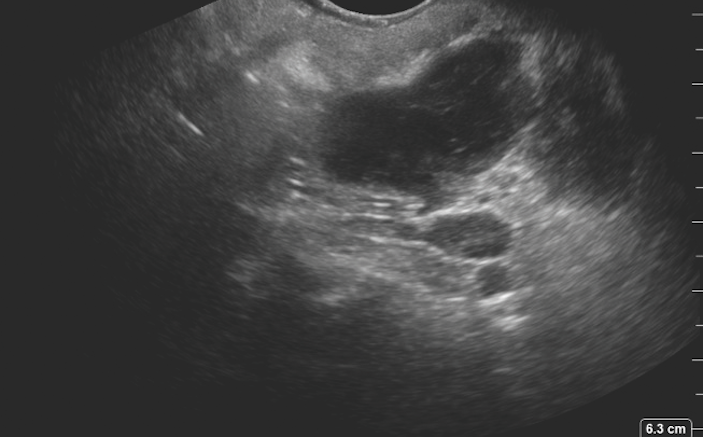

After a warm introduction and assurances to the patient that you will take great care of him, you hand the patient the intracavitary transducer from the ultrasound machine and direct him to place the probe in his mouth and touch where it hurts the most. You’ve placed fresh, clean gel mixed with viscous lidocaine onto the tip of the transducer sheath that covers your intracavitary transducer. With the probe touching the back of the patient’s oropharynx, this is the image you obtain (Figure 1 below).

Query: Is there a drainable fluid collection? How deep should you insert your needle?

Now that you have visualized a nice full pocket of hypoechoic fluid collecting just medial to the tonsil, you have the patient remove the ultrasound probe and carefully anesthetize his oropharynx. It looks like you will need to give yourself about 2 cm of needle depth, so you have your resident cut off 2 cm of the spinal needle cap and replace the plastic cap over the needle to artificially limit the amount of needle available (Figure 2 below). You make special note of where the vascular structures lie in relationship to the peritonsillar abscess you are about to drain and remind your resident not to advance more than 2.5 cm when he is aspirating (Figure 3 below).

You hand your patient the laryngoscope so that he can him insert it into his mouth and pull down on his tongue, maximizing the view of his peritonsillar space. After excellent anesthesia has been achieved, your resident aims the needle just superomedial to the left tonsil and advances until he feels that satisfying pop. You and your patient watch with amazement as you drain off more than 15 mL of purulent peritonsillar abscess fluid (Figure 4 below). After the drainage, you have the patient gargle with ice water to help with vasoconstriction, then you scan through the peritonsillar space again to ensure adequate drainage.

Within moments of the successful aspiration attempt, your patient has regained his voice enough to thank you wholeheartedly for fulfilling your promise. He feels 100% better and is awestruck by how much pus came out of his oropharynx. With a skip in your step after a satisfying procedure, you walk over to your colleagues and share your own Big Fish story of the day.

Pearls and Pitfalls: Using Ultrasound to Evaluate for Peritonsillar Abscess

- Some patients will develop a peritonsillar abscess as their soft tissue cellulitis progresses over time. Bedside, point-of-care ultrasound can be used to identify if a drainable fluid collection has formed within the peritonsillar space.

- To evaluate the peritonsillar space with ultrasound, it is best to use an intracavitary transducer. For obvious reasons, do not refer to the transducer as a transvaginal probe in the patient’s room or during this procedure.

- Place a small amount of gel on the tip of the intracavitary transducer and then cover the probe with a clean transducer sheath. To improve comfort and anesthesia, place some viscous lidocaine mixed with ultrasound gel on the tip of the transducer.

- Have the patient place the probe inside their mouth and touch the tip of the probe to the most painful area in the back of their oropharynx.

- A peritonsillar abscess will appear as a distinct hypoechoic or anechoic fluid collection just medial and superior to the palatine tonsil.

- Use ultrasound to identify the dimensions of the peritonsillar abscess and to discern if any loculations or septations are present.

- Identify surrounding vascular structures and remember that the carotid artery can course just posterior and lateral to the peritonsillar abscess.

- If the patient does not have significant trismus, the peritonsillar abscess can be drained under direct ultrasound guidance. Some patients will have too much trismus to tolerate having both the probe and needle in their mouth simultaneously.

- After incision and drainage or aspiration attempts, repeat the intracavitary scan to assess if the pocket of pus has been adequately drained.