Breaking the myths and exploring future potentials of devices.

Emergency Department evaluation of cardiac-implanted electronic device (CIED) function has progressed rapidly in the past 30 years. In the 1990s, assessment of pacemakers and ICDs could only be performed using CIED programmers, complex devices capable of interrogating CIEDs, altering CIED settings or even turning them off. These devices can only be used safely by International Board of Heart Rhythm Examiner (IBHRE)-certified professionals (usually electrophysiologists or device company representatives). Due to the limited pool of such individuals, community EDs sometimes struggled to have CIEDs interrogated on weekends and holidays, waiting as the nearest company representative traveled to their location.

This changed during the last decade with the introduction of remote CIED interrogators, which can check CIEDs and are unable to alter device settings or affect them in any way. Unlike CIED programmers, remote interrogators can be safely used by any healthcare provider after minimal training. Since the development of remote CIED interrogations, clinicians and researchers have been engaged in a continuous process of identifying and solving problems related to their usage in the ED. This article reviews the history of CIED evolution, addresses selected CIED “myths” and details future directions for remote CIED interrogator research.

History

The first ED use for CIED programmers was to assess volume status. Since volume status is a key variable for managing heart failure patients, researchers realized that it was possible to estimate the fluid volume in the lungs of CIED patients by utilizing transthoracic impedance.

That is, a small electrical current was run from the assessing device to the CIED’s leads, and the impedance of the current varied with fluid volume, allowing clinicians to assess volume status. [1, 2] This technique was effective in its limited scope, and served as proof of concept that interrogating a CIED in the ED could improve patient care.

In 2012, the next advancement arrived when engineers uncoupled CIED programming functionality from interrogation functionality, allowing for the assessment of CIED function without the risk of accidentally turning off or reprogramming the CIED. This was a crucial step in the development of remote interrogators, ensuring their safety in the hands of non-IBHRE trained healthcare personnel. These devices were originally intended to be used by patients at home, but healthcare providers soon realized that they could be of use in clinical settings as well, especially the ED and post-anesthesia care unit.[3] As such, remote CIED interrogators gained traction in the clinical setting, and today are widely used across the country.

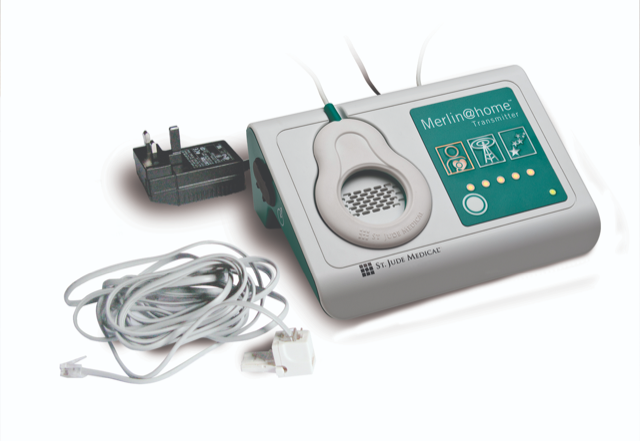

Each of the three major US CIED manufacturers produces a read-only CIED interrogator — the Abbott Laboratories Merlin On-Demand (Fig 1.), the Boston Scientific Latitude Consult (Fig 2) and the Medtronic Carelink Express (Fig.3). These devices are widely-used, with over 2,000 estimated to be in use in US hospitals.

Despite their relative acceptance in the clinical setting, myths concerning the utility and safety of remote CIED interrogators persist. Here is a selection of studies that have addressed these myths.

Myths

Myth #1: Remote CIED interrogators can harm patients.

Despite the fact that remote CIED interrogators were specifically designed to be safe for any provider to use with minimal training, their use wasn’t rapidly adopted, as some clinicians still worried that remote interrogators could cause device malfunction. A variety of studies have now shown that remote interrogator use is not associated with adverse events, but is associated with shorter wait times for the CIED to be checked.[4-6]

Myth #2: Remote interrogators are not useful in the emergency department, because most patients whose complaints requires CIED interrogation will eventually need to have their CIED reprogrammed anyway.

The premise of this idea seems logical – why bother utilizing remote interrogators if most patients who receive an interrogation will require a device rep to use a programmer anyway? In reality, this claim is not supported by data. A recent study analyzed the results of 182 remote CIED interrogations performed in a community hospital from 2015-2017.

The authors found that of the 182 interrogations performed, only seven (4%) found results requiring immediate device intervention, such as improper programming in relation to the patient’s disease state. The remaining 175 interrogations either revealed properly functioning devices, or non-time sensitive issues such as low battery.[7]

These findings are in line with similar studies and demonstrate that remote CIED interrogation rarely results in the necessity of calling a device company representative, instead helping emergency physicians avoid the hassle of calling in a representative to interrogate a properly-functioning CIED.[3, 8]

Myth #3: Interrogating a given brand’s CIED with another brand’s remote interrogator can cause CIED malfunction.

This myth is also rooted in questions surrounding remote interrogator safety. Physicians worried that, if a patient mistakenly stated that their CIED was produced by the incorrect manufacturer, interrogating that CIED with a brand-mismatched remote interrogator could cause CIED malfunction.

If that was the case, the liability and risk involved in remote interrogator usage would mean that physicians would be better off just calling a company representative. To the contrary, recent research has shown that brand-mismatched remote interrogation is not associated with CIED malfunction.[9] Investigators attempted to interrogate a total of 75 ex-vivo CIEDs (25 from each major manufacturer) with brand-mismatched remote interrogators for two minutes each, eventually performing 150 “brand-mismatched interrogations.”

Company representatives assessing the devices with programmers found that none had been turned off or had any settings changed. This procedure was then repeated with CIEDs implanted in patients. Again, no devices were turned off or had parameters changed after brand-mismatched remote interrogation. This suggests the safety of mismatch interrogation.

Some providers even utilize mismatch interrogation to interrogate CIEDs of unknown manufacturer (attempting to interrogate with each possible remote interrogator until one connects). This situation is specific, but not irrelevant. One study found that only 55% of patients presented to the ED with their manufacturer-assigned device identification cards.[10]

Future Directions

Further research is necessary to determine the full range of applications for remote interrogators in the ED. For example, anecdotal reports of CIED malfunction after only minor trauma suggest that interrogating the CIEDs of many trauma patients could be worthwhile. In terms of large-scale research, questions exist whether remote interrogator use in the ED is linked to improved outcomes, such as increased patient satisfaction or decreased ED length of stay.

A study could measure those variables in patients presenting to the ED with potentially CIED-related complaints who received remote interrogation compared to those who had their devices interrogated by company representatives. Other directions include studying the utility of these devices in rural areas with poor access to electrophysiology care, such as assessing whether remote interrogator usage decreases the rate of CIED patient transfer from such institutions.

Note:

Providers interested in obtaining remote CIED interrogators for use in their institutions can contact:

Abbott: 1-800-PACEICD 800-284-6689

Boston Scientific: 1-800-CARDIAC 800-227-3422

Medtronic: 800-633-8766

References

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, Chan RH, Kong SL, Tang MO et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112(6):841-8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207.

- Wang L. Fundamentals of intrathoracic impedance monitoring in heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(10A):3G-10G. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.02.009.

- Ahmed I, Patel AS, Balgaard TJ, Rosenfeld LE. Technician-Supported Remote Interrogation of CIEDs: Initial Use in US Emergency Departments and Perioperative Areas. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2016;39:275-281.

- Neuenschwander JF, Hiestand BC, Peacock WF, et al. A pilot study of implantable cardiac device interrogation by emergency department personnel. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2014;13:6-8

- Neuenschwander JF, Peacock WF, Migeed M, et al. Safety and efficiency of emergency department interrogation of cardiac devices. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2016;3:239-244.

- Fondriest SA, Neuenschwander JF, Migeed M, Peacock WF. A comparison of implanted cardioverter/defibrillator interrogation protocol effectiveness between 2 patients in the Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:680-682. Neuenschwander J, Le T, Parekh A, Hiestand B, Cordial P, Le H et al. Utilization of a Read-only Pacemaker and Defibrillator Interrogator in the Emergency Department and Hospital. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. doi:10.1111/acem.13950. Mittal S, Younge K, King-Ellison K, Hammill E, Stein K. Performance of a remote interrogation system for the in-hospital evaluation of cardiac implantable electronic devices. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2016;46:121-128.

- Le T, Neuenschwander J, Sankoe M, Miller P, Cordial P, Wilson C, Cedoz K, Le H, Hiestand B, Peacock WF. (404) Interrogations of Pacemaker/Defibrillator With Mismatched Read-Only Interrogators Does Not Cause Malfunction. Academ Emerg Med. 5/2019 26(S1) S156

- Daugherty C., Le T.S., Peacock, W.F., Le, T.S., Cordial, P., Panian, J., Hammill, E.F., Kojasoy, T., Hiestand, B.C. Neuenschwander, JF. 45% of Pacemaker and Defibrillator Patients Present Without Device Identification Cards.” JETS. 7/2018 11 (3) 234