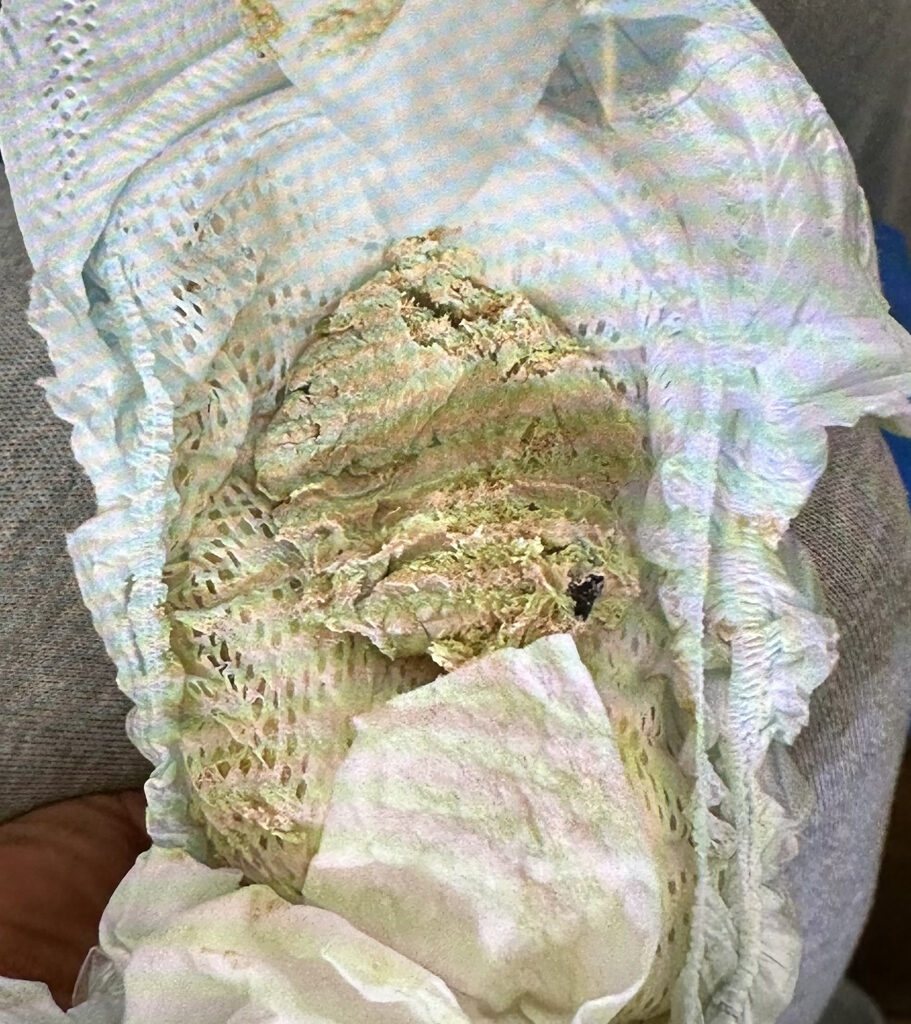

A 17-month-old female was brought to the emergency department with concern for white-greyish stool in her diaper that morning (figure 1).

The parents noticed a similar stool sample several months ago but has resolved prior to her being seen by her pediatrician. The parents stated that she was a normal full-term delivery and had no medical problems, took no medications, and had no known allergies. The mother stated that the baby had two episodes of vomiting and diarrhea three days prior to presentation but otherwise had been healthy.

There were no sick contacts, no fever or rash, upper respiratory symptoms, abdominal pain, or difficulty breathing. The parents stated that she had not been as playful as usual for the past 2-3 days and that she has had a reduced urine output in her diapers. Mom had administered acetaminophen and ibuprofen the night before due to a fever of 101C, which seemed to help with her general symptoms.

On physical examination, the child was alert, attentive, and in no distress. Her vital signs were BP 89/59, pulse 160 and she was afebrile; her pupils were 3-2mm round and reactive and the sclera were nonicteric; her membranes were moist and there were occasional tears on exam; the tympanic membranes were normal and her cardiac exam revealed tachycardia with clear lung fields; her abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds without any mass or tenderness; no rash was identified and she moved all her extremities appropriately.

Labs were ordered including a BMP, CBC, LFT’s, lipase, and magnesium during which time ibuprofen was administered as well as a bolus of lactated ringers for possible dehydration based upon her initial low blood pressure and elevated pulse.

Her lab work revealed: normal magnesium, BMP, and CBC with a markedly elevated lipase at 1922 (18-32 IU/L), elevated levels of: SGOT 147(13-39IU/L), SGPT 581(7-52IU/L), total bilirubin 3(0.3-1.0mg/dL), indirect bilirubin 1.62(0.03-0.18mg/dL), alkphosphatase 411(132-315IU/L), and CRP 5.6(<0.5mg/dL).

The patient was started on piperacillin/tazobactam due to the concern for an ascending cholangitis. In the emergency department, she was able to eat a popsicle and appeared somewhat better with improvement in her blood pressure and decrease in her pulse after fluid administration.

She was admitted to the pediatric service for further management and evaluation. An abdominal ultrasound was ordered but not completed prior to her admission.

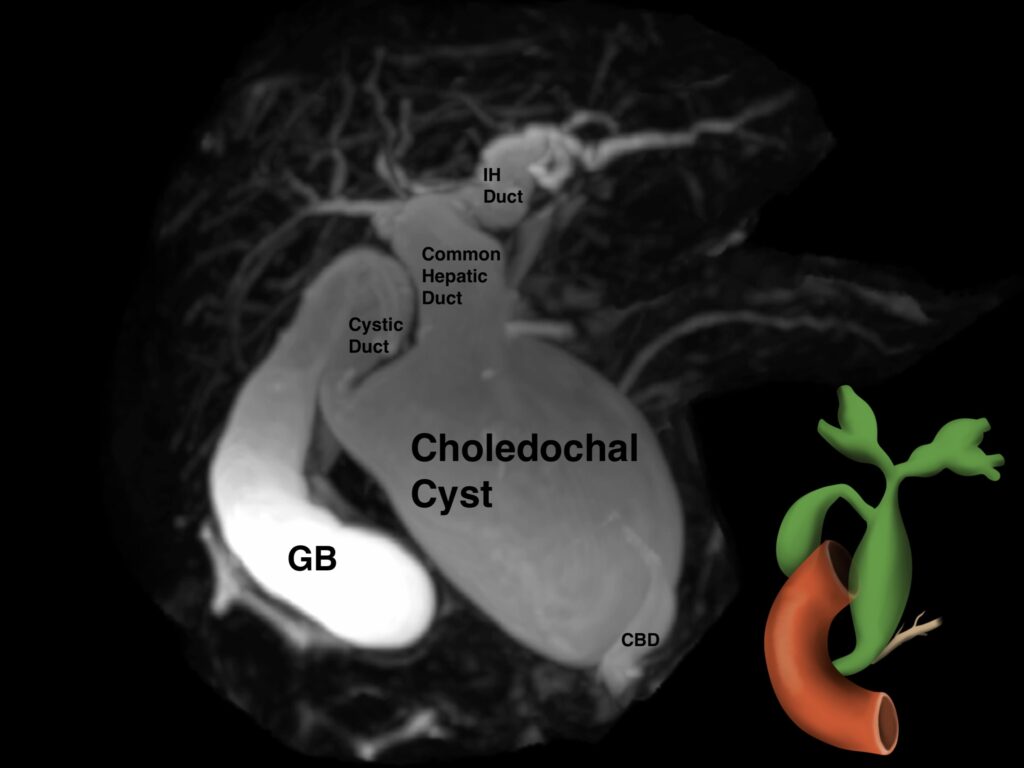

On arrival to the floor, IV piperacillin/tazobactam was continued for possible acute cholangitis given her fever and elevated WBC’s and Ursodiol was initiated to help with biliary sludge. The patient was kept NPO and started on TPN to provide bowel rest. USG liver/gallbladder/pancreas showed an enlarged (33 mm) anechoic cystic structure continuous with the common bile duct (CBD) and intra-hepatic biliary dilation with a negative Murphy’s sign (figure 2).

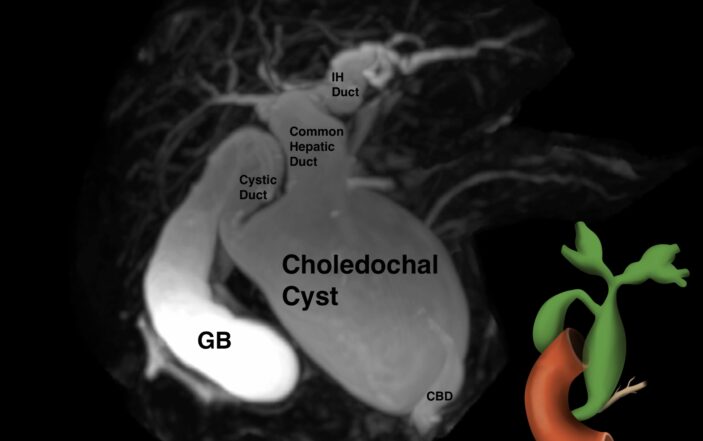

Due to concerns for a choledochal cyst, an MRCP was done which confirmed the presence of type 4 choledochal cyst.

On MRCP, there was a cystic dilatation of the CBD (5.9X5.1X4.2 cm) with irregular central intrahepatic bile duct dilatation. There were no gallstones or wall thickening noted in the gall bladder (GB). A stone (0.6 X 0.6 cm) was visualized in the accessory distal pancreatic duct, but the main pancreatic duct had no dilations/radiological signs of acute pancreatitis (figure 3).

During the hospital stay, the child had another episode of clay stool but otherwise remained asymptomatic. Due to lack of laparoscopic services being available for her condition, the patient was transferred to a different center where she was underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy with cyst removal and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. As of her most recent follow up, she has been asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

Choledochal cyst (CC), now better termed as choledochal malformations, are congenital cystic dilatations of the extra and/or intrahepatic biliary tree [1]. Despite widespread controversies surrounding different theories, the exact cause is still unknown but the most popular, mainly type I and type IV, involve an anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ) with resultant backflow and mixing of pancreatic and biliary secretions, which in turn causes pancreatic enzyme activation. This triggers a pathway which is characterized by increase intraluminal pressure, dilatation, inflammation, dysplasia and even malignancy in some [2].

Though there are different classification of CC’s that have been proposed, the most popular and widely used is by Todani and et al., which categorizes CCs into 5 different types based on the extent of involvement of the extra and/or intrahepatic ducts [3].

Type I cysts involve cystic dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD) and is divided into IA, IB and IC depending upon the extent of involvement of the CBD and presence/absence of APBJ. It is the most common type comprising of 50-80% of all the CC’s. Type II consists of the diverticular dilatation anywhere along the length of extrahepatic duct. Type III consists of intraduodenal cystic dilatation of the distal CBD and is termed as choledochocele.

Type IV cysts are the second most common (15% to 35%) and characterized by multiple cystic dilatations. When these involve both the extra and intrahepatic biliary tree, it is called IVA and when it is restricted to just the extrahepatic tree, it is known as IVB. Type V cysts are characterized by multiple intrahepatic biliary tree dilatations and known as Caroli’s disease [2,3].

The clinical presentation of CC’s are non-specific and though commonly diagnosed in children, they can even go unnoticed until adulthood [2]. The classic triad of CC’s which comprises jaundice, palpable right upper quadrant abdominal mass, and abdominal pain are present in only 20% of the cases with majority of the children presenting with only the former two parts of the triad [2,4]. The more common initial presentations are often ascending cholangitis and pancreatitis which was also seen in our patient [4].

In our case, the child also presented with acholic or clay-colored stools, which can be seen in any condition that affects bile formation or flow since the color of the stool is due to the pigment, stercobilinogen, present in the bile [5].

The differential diagnosis of acholic stool can be divided into conditions which affect bile formation and those affecting bile flow. Bile formation can be affected in diseases affecting the hepatocyte function such as infections or metabolic disorders (galactosemia, antitrypsin deficiency, etc) and bile flow obstruction can be seen in conditions affecting canalicular membrane transporters (progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis) or those that cause intra and/or extra hepatic obstructions such as cystic fibrosis, biliary atresia, biliary atresia, choledochal cyst and cholelithiasis [5].

Ultrasound is the initial investigation of choice with MRCP being the gold standard for diagnosis (2). This was followed in our case as well where CC’s identified on the USG were confirmed with MRCP. Though ERCP has the highest diagnostic accuracy, it is less favored due to its associated complications such as ionizing radiation, perforation, ascending cholangitis and pancreatitis which are not seen in MRCP [2].

Total cyst excision with hepaticoenterostomy as early as possible is the standard of care in favor of the previous approach of external/internal drainage due to risk of complications, especially malignancy [2,4,5].

The mode of bilioenteric can be Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy or hepaticoduodenostomy with the former more commonly done due to higher risk of biliary and gastric malignancy secondary to bile reflux into the stomach reported with the latter approach [2].

However, the management of type II, III and IV can vary depending on the type and extent of disease involvement ranging from simple cyst excision, sphincterotomy, or segmental hepatic resection when the disease is localized [2]. The management of the intrahepatic portion of type IVA seems to be controversial, with some surgeons favoring removal of just the extra hepatic portion while segmental hepatic resection being preferred by some when the intrahepatic cyst are localized [4].

The risk of malignancy is what drives the early management of CC’s. A 2018 meta-analysis reported the risk to be almost [1].

Malignancy has even been reported in postoperative cases, with higher cases following cystic drainage in comparison to complete cyst removal, particularly in type I and IV, hence necessitating long-term follow up after cyst removal [1].

REFERENCES

- Ten Hove A, de Meijer VE, Hulscher JBF, de Kleine RHJ. Meta-analysis of risk of developing malignancy in congenital choledochal malformation. Br J Surg. 2018 Apr;105(5):482-490.

- Hoilat GJ, John S. Choledochal Cyst. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557762/

- Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977 Aug;134(2):263-9.

- Metcalfe MS, Wemyss-Holden SA, Maddern GJ. Management Dilemmas With Choledochal Cysts. Arch Surg.2003;138(3):333–339.

- Nikolaidou O, Saliakellis E, Sotiriadou F, Batsi O, Beropouli S, Fotoulaki M. Clay-Like Stool in an Otherwise Asymptomatic Toddler: A Surprising Diagnosis. Clinical Pediatrics. 2022;61(3):256-258.

Figures:

1. Child’s diaper with acholic colored stool

2. Ultrasound liver, gallbladder, and pancreas demonstrating an enlarged common bile duct 33mm (average 3mm) with an enlarged anechoic cyst contiguous with the common bile duct, hepatomegaly 11.4cm (average 7cm), and mild accessory distal pancreatic duct dilatation

3. MRI spin cycle demonstrating Type 4 choledochal cyst

Authors:

- Y. Dirkipa MD PGY1 pediatric resident, department of pediatrics, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio

- Murphy MD attending physician, department of Pediatrics, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, assistant professor Case Western University, Cleveland, Ohio

- Jones DO attending physician, department of Emergency Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center, professor Case Western University, Cleveland, Ohio

D. Effron MD attending physician, department of Emergency Medicine, attending physician, department of Emergency Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center, associate professor Case Western University, Cleveland, Ohio