While travelling along the interstate between who-knows-where and woebegone—a long way from any EMS services—you come across a rollover accident that has just occurred. For some reason you’re not carrying any medical equipment. (Why not?) One of the van’s former occupants is in respiratory distress from a chest injury and needs a chest tube. When you ask, a trucker who has also stopped says that he has some tubing in his truck. So, now you need a scalpel.

The first installment in EPM’s series on improvised medicine. First up: what to do when you need to fashion an ad-hoc blade with surgical sharpness.

While travelling along the interstate between who-knows-where and woebegone—a long way from any EMS services—you come across a rollover accident that has just occurred. For some reason you’re not carrying any medical equipment. (Why not?) One of the van’s former occupants is in respiratory distress from a chest injury and needs a chest tube. When you ask, a trucker who has also stopped says that he has some tubing in his truck. So, now you need a scalpel.

In desperate situations, surgery can be performed with any clean, preferably sterile, sharp object. This could include the lid from a can (folded off center to form a non-sharp handle and a single blade) or a piece of glass. Nearly any piece of metal can be sharpened to act as a knife. As a case in ‘point,’ observe the ingenuity with which prisoners make “homemade” knives. To hone the blade, not just the tip, to surgical sharpness takes special metal, tools, and expertise. The best option if this is the route you must take is to start with a cutting knife and sharpen it as well as possible.

A frequent situation is to have a scalpel blade, but no handle. In many places around the world, they are still packaged separately. In such cases, a good option is to hold the base of the blade with a straight clamp, such as a needle holder, and use the clamp as a handle. Alternatively, clamp the blade with needle-nosed pliers or similar implements, which are often found on universal tools (e.g., Leatherman, Victorinox, SOG, Gerber). Of course, you may want to use one of the knives that usually come with these tools if it is very sharp and relatively clean.

My first experience with makeshift scalpels was while performing an emergency cricothyrotomy in a medical ICU, whose staff exclaimed when I asked for one, “What do you mean, a scalpel? This is a medical ICU” (This was the mid-1970s).

They found a #15 scalpel blade in a box labelled “Procedure Kit,” and I held it between my fingers. The procedure was successful, and the patient survived.

More commonly, improvised scalpels are knives that have been suitably cleaned and sharpened, when possible. They may even become the routine surgical instruments, as happened periodically during World War II. Dr. J. Markowitz, the surgeon at Chungkai jungle hospital camp in Thailand, crowded with 7000 POWs, performed 1,200 operations using a carpenter’s saw and a few butcher knives that were repeatedly re-sharpened.

Razorblades, at least as sharp as surgical-grade scalpels, can also be carefully held between one’s fingers. It’s easiest to do with the older, larger blades still found in surgical prep razors, as well as in most developing countries. If it is a two-edged blade, it is safest to wrap one side with tape before you use it.

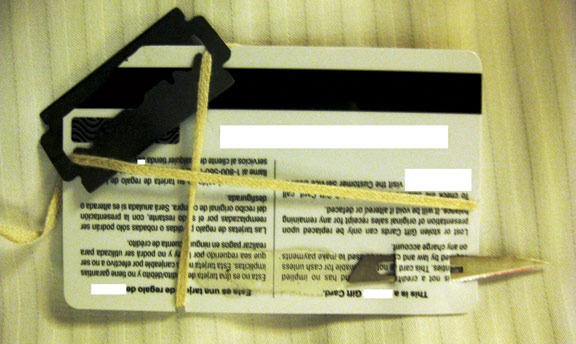

With a bit more time, excellent cutting edges of various sizes can be easily made from inexpensive (about 1¢ U.S./blade) razor blades. One razor blade provides up to six surgical knives, three blades from each edge. The best way to use them is to hold pieces of the blade with a “razor blade breaker,” no longer common in industrialized countries, but still sold and used internationally. The entire blade can also be easily affixed to the flat handles of eating utensil or affixed to a credit card. Carbon steel blades work better than stainless steel blades but, to retain their sharpness, they must be chemically sterilized rather than steam-autoclaved or boiled.

Multi-blade, disposable razors are the norm in the U.S., Canada and other developed countries. To use these as scalpel blades, carefully separate the blades from their plastic holder by using a tool to bend one end, causing the blades to pop out.Small enough to be dangerous to one’s fingers, the blades should be held using another tool (e.g., clamp or universal tool) or, if time permits, secured to a piece of wood (e.g., tongue depressor) or credit card for one-time use, or to a piece of metal (e.g., spoon handle) for repeated uses after sterilization. Flat-handled metal spoons, forks, or knives are good options. The handle must be flat for the blade to adhere; for butter and similar knives, the straight part (back) of the blade can be used. Spoons seem to be the easiest handles to hold.

Attach the disposable blade or the piece of the larger blade to the handle with a few drops of cyanoacrylate (e.g., Superglue or tissue adhesive) on both the blade and the utensil/holder. You may need to wait about 10 minutes before larger blades are firmly fixed, less time for the smaller multi-blade disposables. Be sure that the blade extends beyond the side of the handle and is parallel to the opposite side of the handle for better scalpel control.

How often will you need an improvised scalpel? You may need to improvise anytime you face a medical emergency and lack appropriate medical equipment. (Carrying a medical kit in your car helps reduce that risk.) In life-threatening emergencies when improvisation is the only option, don’t hesitate to do whatever is necessary to save a life. However, when you can buy time with more conservative approaches, use your clinical judgement.

Improvised Medicine The Book

EPM’s new series on providing care in extreme environments will be pulled from Dr. Ken Iserson’s book, Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments (McGraw-Hill). This book covers topics from diagnosing and treating dental emergencies to providing general anesthesia to managing disasters. Sections also describe how to make and use very basic laboratory equipment (e.g., centrifuge, incubator, refrigeration, and sterile water), diagnostic equipment (e.g., precordial and esophageal stethoscopes, improvised ECG leads, ophthalmoscope without lenses), and treatment modalities (e.g., postpartum hemorrhage, rapid inexpensive blood warming, rehydration without IV or IO needles, and swagged sutures, endotracheal tubes, and catheters). Emergency Physician Monthly readers can purchase the book from McGraw-Hill at the special reduced price of $43.20 (Regularly $54.00) at: www.mhprofessional.com/promo/index.php?promocode=iserson&cat=39

EPM’s new series on providing care in extreme environments will be pulled from Dr. Ken Iserson’s book, Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments (McGraw-Hill). This book covers topics from diagnosing and treating dental emergencies to providing general anesthesia to managing disasters. Sections also describe how to make and use very basic laboratory equipment (e.g., centrifuge, incubator, refrigeration, and sterile water), diagnostic equipment (e.g., precordial and esophageal stethoscopes, improvised ECG leads, ophthalmoscope without lenses), and treatment modalities (e.g., postpartum hemorrhage, rapid inexpensive blood warming, rehydration without IV or IO needles, and swagged sutures, endotracheal tubes, and catheters). Emergency Physician Monthly readers can purchase the book from McGraw-Hill at the special reduced price of $43.20 (Regularly $54.00) at: www.mhprofessional.com/promo/index.php?promocode=iserson&cat=39

1 Comment

You might be interested in this paper http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22562071 that we recently published