Health Care Providers (HCPs) are trained to recognize victims of elder abuse, child abuse and general domestic violence. When it comes to identifying victims of sex trafficking, however – an area where clues can be very subtle – there is a marked lack of practical education. A study by Barrows and Finger in 2008 demonstrated that only 13% of HCPs felt confident they could identify a trafficked victim, and only 3% of medical personnel had received any training on identifying victims.

Health Care Providers (HCPs) are trained to recognize victims of elder abuse, child abuse and general domestic violence. When it comes to identifying victims of sex trafficking, however – an area where clues can be very subtle – there is a marked lack of practical education. A study by Barrows and Finger in 2008 demonstrated that only 13% of HCPs felt confident they could identify a trafficked victim, and only 3% of medical personnel had received any training on identifying victims. This study was conducted in major cities across the United States within large medical facilities. JHACO requires hospital emergency departments (EDs) to have a written protocol to identify and screen for domestic violence and elder and child abuse as well as a plan for educating staff in this regard (Future without Violence Fund, 2012). Mandatory education and protocol development in the area of sex trafficking does not readily exist in our health care settings, but is needed given the growing epidemic of this problem in the US.

The following are three cases of real sex trafficking victims who presented to an emergency department, offering a glimpse at the red flags you could be missing. These real-life stories will be our guide as we walk through how sex trafficking victims present, and how you, the emergency medicine provider, should approach them.

Case 1

An 18-year-old female presents to the emergency department with a vague complaint of back pain for several days. She is wearing street clothes—a slightly short skirt with a tank top. The patient has several tattoos. She comes in with an older man who appears to be her boyfriend. During the history-taking, the man often interjects and answers for the patient. It is explained that she has had this back pain before and it feels like her usual pain. When the young woman does speak, her speech is pressured and she appears to be in a hurry. The patient states her last menstrual period was five days ago. She asks for a shot of pain medicine and Percocet for home. Her physical exam is performed while she is in her clothes. There is no evidence of neurological deficits, and the etiology appears to be musculoskeletal. Medical record review confirms she has been there before with back pain. The man she is with remains in the room for the entire visit. The patient is given pain medication and sent home. She has no primary care provider; she is given the referral line.

Two days later, the “boyfriend,” driving an SUV, pulls up to the ambulance bay, pushes the patient out of the car, and drives away. The patient appears blue and is minimally responsive with signs of shock. Resuscitation is attempted, but is unsuccessful. On coroner exam she is noted to have several bruises to her low back, upper thighs and chest wall. She has a retained “makeup sponge” in her vagina with a large amount of pus. She has a man’s name tattooed across her lower left breast. There are skin lesions that appear to be cigarette burns at her abdomen and volar wrists.

Case Discussion – The victim presented with her “boyfriend” who was really her pimp. The vague complaints of back pain appeared more consistent with her typical back pain, however; because the patient was evaluated in her clothes the provider was unable to see some of the bruising, branding/tattoos that may have helped the provider suspect abuse. The pimp was in the room the entire H & P; this did not allow the patient to speak freely. On autopsy of a makeup sponge was found in the vaginal cavity. Makeup Sponges are often used to hold off menstrual flow, enabling a sex trafficking victim to “work” while menstruating.

Case 2

A 17-year-old female presents to the ED with a complaint of heavy vaginal bleeding. She presents without a parent. She states she was dropped off by her “Daddy” because he has a business meeting. Her mother works as a nurse at another facility and gives verbal consent to treat over the phone. The patient states she is on her menses. It is much heavier than usual and she has cramping. She is not asked about sexual activity or history of abuse. She appears fearful. She is wearing a Catholic school uniform she just has just worn from school. She has no other complaints. The patient is taken to an exam room and examined with her clothes on. She has heavy makeup on her face with a slight darkness noted under her eyes. There is no focal abdominal tenderness by exam. The provider explains that she is likely having a heavy menses. She is given Motrin and sent home without any other work-up.

The pain continues and the bleeding becomes heavier with clots. She returns to the ED about 10 days later (after again being dropped off by her “Daddy”) and is evaluated by another HCP who asks her about sexual activity, and performs labs related to pregnancy. She is found by exam to have retained products of conception and needs a D&C for a miscarriage.

Case Discussion – She was an underage girl without parental involvement in her care. Her “Daddy” who dropped her off in the ER was really her pimp. The verbal consent obtained over the phone by her “mom,” was sufficient for this hospital. On initial presentation she was having a miscarriage. Unfortunately, a pregnancy test was never done; her physical exam was completed while she was fully dressed. Had she been undressed the bruising to her upper thighs may have been noticed. Also, her face contusion that was poorly covered with makeup was not noticed. Sadly, this victim’s mother (who really was a nurse) actually participated in “pimping” her daughter out.

Case 3:

A female minor is placed in detention and given a standard examination. When the case worker meets with, the girl has no apparent swelling or bruising. After a week of detention she is placed at home and her mother calls saying she is complaining of pain to her face. The girl is referred to a local hospital where she is found to have seven facial fractures. These seem to have occurred from a beating she sustained from her pimp before we recovered her.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

As with most victims of abuse, the presentation of sex trafficking isn’t going to be straight forward. Rarely is a victim brought in for a complaint of “sexual assault.” The victim is more often brought in for a banal complaint such as “cough” or “fever.” Because of the long term trauma and manipulation endured by the victims, they often do not consider themselves to be victims—making it all the more important for HCPs to have the skills to recognize these downtrodden girls/women.

Making matters worse, there is mistrust of HCPs, the healthcare system, and for authority figures in general. Sex trafficking victims have had customers from all walks of life which include health care workers, members of law enforcement, clergy members, educators, and politicians. Even outside the sex trafficking arena they are frequently treated in derogatory and discriminatory ways by established members of society. I

n addition, victims are coached by their pimps to lie to practitioners—to give fabricated histories with scripted stories, and identification, and often to project a more socially acceptable persona, for example, that of a college student.

Red flags/Indicators

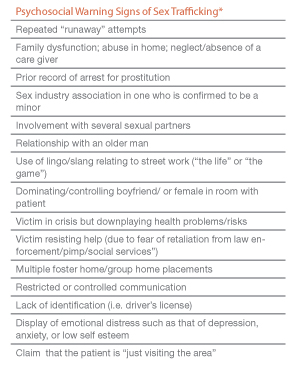

There are several red flags that may help the HCP in identifying victims. Most victims have a conglomerate of indicators, but the provider may only be exposed to one in a particular emergency department visit. Survivors of sex trafficking will have a significant history of trauma over an extensive amount of time by multiple perpetrators. Discovery of even one of these presenting signs/symptoms should trigger further investigation (see tables on opposite page).

Mental Health

Mental Health

Victims often need psychiatric care and may have extreme psychiatric presentations including those of PTSD, dissociation, multiple personality disorder and acute psychosis. (Rhoades & Sar, 2005). It is important to investigate for events that could have contributed to the patient’s mental state. It would be easy to treat a patient for psychiatric illness without discovering the patient has been a sex trafficking victim.

Approach of the Clinician: History-taking and identification

Should you suspect that a patient could be a victim of sex trafficking, the key first step in an evaluation is to get the patient alone in a confidential location for the interview. Having the captor/ pimp/trafficker at the bedside will obviously hinder the assessment. Keep in mind that certain rules and precautions regarding this need to be followed if the patient is a minor.

Consider temporarily separating the patient from her belongings as well as from the people with her. The victim may be wearing or carrying a tracking/communication device such as a GPS transmitter that divulges her location or a cell phone that allows the captor to hear everything that is occurring.

Sometimes victims present in police custody. This is a prime time to conduct a thorough history and exam. Utilize established assessment and examination guidelines for victims of physical and sexual abuse in your evaluation.

Establishing rapport and trust during the initial assessment is critical. As with any patient encounter, one must convey compassion and listen empathically. Maintain eye contact and treat the victim as an equal. This can be a foreign concept for these girls given that they are often viewed as an object. Light conversation initially helps the victim to let down her defenses. Emphasize you are there to assess her entire health and that the questions you are asking will help make sure her body is healthy.

Establishing rapport and trust during the initial assessment is critical. As with any patient encounter, one must convey compassion and listen empathically. Maintain eye contact and treat the victim as an equal. This can be a foreign concept for these girls given that they are often viewed as an object. Light conversation initially helps the victim to let down her defenses. Emphasize you are there to assess her entire health and that the questions you are asking will help make sure her body is healthy.

Let the victim know that there is help available and a safer place to go. Traffickers also tell their victims, “I am here to help you,” so we must describe clearly the way in which we are going to help. Avoid questions that sound judgmental. Avoid questions prefaced with “Have you ever…,” to avoid alienating the patient. Expressing to the victim that the sex trafficker “does not love her” must be avoided until further into the treatment and recovery process.

Truly “seeing” their situation for what it is even though it is ugly, complicated and evil. This population lives in fear. Fear for what is “behind their back;” ready for the next person to let them down or abandon them.

Conduct assessment in a safe and comfortable environment. Vulnerability is extremely difficult. For most victims their dignity has been stripped away and in their mind you could be just another person who uses them.

Their lives have been tainted with abuse and they have had customers from every walk of life and they begin to have a warped view of the world and who is truly trust worthy. They are radars for the disingenuous, and quickly able to perceive true sincerity.

After Identification, what do I do?

Identification of sex trafficking victims in a health care setting is new, and most emergency medicine providers have received little, if any, training to help in this regard. HCPs and health care facilities must network with their community to find out what agencies are involved in helping sex trafficking victims before a victim presents. Standard guidelines regarding these cases do not exist. Victims have unique aftercare needs given the depth of the abuses they have experienced. There is an extreme shortage of aftercare resources for these victims.

There are few proven treatment plans specific to these victims, and “long-term homes” for victims are almost non-existent.

1. Identify what organizations may be offering help in your community.

2. If the victim is under 18, it is mandatory under federal law to report sexual exploitation of children, and there are established professionals to which the patient may be referred. Notify the police, sex crimes vice squad, and/or Child Protective Services.

3. If the victim is over 18, reporting sexual exploitation is not mandatory, and this can hinder rescue of a victim. In most cases, the adult victim must agree to a referral. This requirement can be an impediment, because the victim may need counseling before realizing she is a victim, and she may refuse help up until that point. Getting a social worker, justice advocate, or volunteer who specializes in sex trafficking to the bedside is a great help in assessing and handling the situation.

4. Obtain “outreach” cards” or “local hotline” cards to give to victims. Keep the cards small and discrete. Until more advocacy and support groups are available, a great first step is to call the National Human Trafficking Resource Center to report the incident and ask for help. The center’s phone number is 1-888-373-7888.

Don’t be discouraged if the victim is hesitant to leave her situation or resistant to the aid that is offered. Leaving the “game” is extremely difficult for these victims. The victim truly believes that the pimp is in love with her and through a very calculated seasoning process the pimp has completely brainwashed and created trauma bonding with the victim.

The most important message to convey is that you are empathic, willing to help, and have an “open door policy,” so that the victim feels comfortable returning when she is ready.

Conclusion

It is important to realize sex trafficking does exist here in the United States and that there is a significant population at risk. Increasing awareness of the issue of sex trafficking, especially of children, has lead to an increase in the number of victims coming forward to leave the streets. More long-term residential homes are needed. As health care providers, it is our duty to learn to identify and help victims. As emergency providers, we specialize in caring for high risk patients, so it would be a travesty to neglect this population. The emergency department encounter may be the one chance to save a victim’s life.

As more individuals become aware of the issue of sex trafficking and the greater issue of human trafficking in general, a so-called “modern day underground railroad” is emerging. Each member of society with his milieu of experiences and expertise can play his part as an active abolitionist to end the modern day slave trade. Edmund Burke presented the challenge eloquently two centuries ago, “all that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men and women do nothing” (Batstone, 2007).

Indoctrination –

Sex trafficking victims endure vast quantities of physical and emotional abuse. They are threatened and beaten. The girls/women often live in fear of the physical or emotional harm that awaits them. They guard themselves—always preparing for the next person to let them down or abandon them.

Victims of sex trafficking feel and actually are isolated from society. The pimp brainwashes them to believe no one cares about their well-being other than the pimp. The girls/women are robbed of their self esteem and ability to think for themselves. They are lead to believe that turning tricks is their purpose in life—all they are good for.

Many are manipulated into believing that life in “the game” is only temporary and is the means to an idyllic life with their true love. Pimps say things like, “Once we build our empire together, you and I can get married and start a family, and you can have everything you dreamed of.” Simultaneously, they label the girls/women as “whores” and make it clear they can never go back to being “normal,” now that they have sold themselves for sex. Often, the only hope a victim sees for a future is the one the sex trafficker promises if she keeps up her end of the bargain and brings in the money.

Jessica Munoz, RN, BSN, MSN, APRN-RX, FNP-BC is a practicing emergency nurse practitioner in Hawaii. She has spent the past 5 years working in the arena of human trafficking. She is currently the volunteer director for the Courage House Hawaii ™ project whose goal is to build a long-term residential home for underage victims of sex trafficking in Hawaii.

Reference:

- Cole, H. (2009). Human trafficking: implications for the role of the advanced practice forensic

- Nurse. American Psychiatric Nurse Association. 14(6), 462-470

- Cooper, S., Estes, R., Giardino, A., Kellogg, N., & Vieth. (2007). Child Sexual Exploitation.- Quick reference guide. GW Medical Publishing Inc. St Louis

- Dovydaitis, T. (2010). Human Trafficking: the role of the healthcare provider. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 55(5) 462-467

- Future without Violence Fund. (2012). Comply with Joint Commission Standard PC.01.02.09 on victims of abuse. http://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/section/our_work/health/_health_material/_jcaho

- Polaris Project. (2012). Human trafficking resources for the service provider. Retrieved on april 4, 2012 from http://www.polarisproject.org/

- Rhoades & Sar. (2005). Trauma and Dissociation in a cross cultural perspective. Hawthorn Press. New York, NY

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Human trafficking resources. Retrieved on march 3, 2012 from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/trafficking/

1 Comment

3 charts to identify st

1. words not to say

2. psychological chart

3. physical s/s of st