One of your most experienced emergency medicine residents sits down next to you and conveys more than her usual air of certainty. “This patient with right-lower-quadrant pain was sent over by her PCP after being told we would obtain a CT for suspected appendicitis. Her office CBC was 13.2 while her urine pregnancy test and UA were negative. I went ahead and ordered the CT.” Your resident reports the patient as pre-menarchal and even checked to rule-out an imperforate hymen. Although the community physician is known to be quite competent, you have to work hard to conceal your frustration that he created an expectation for a CT scan.

“Do you know if she has actually been transported to CT yet?” Your resident’s expression suggests she doesn’t know, so you jump up as quickly as your septuagenarian legs allow and head to the patient’s room.

The patient is a moderately endomorphic 12-year-old female who is sitting up in the ED bed. She and her mother attest to increasing abdominal pain that began in the right-lower quadrant about five days ago. They affirm considerable tenderness during the examination in the PCP’s office. Although the patient and her mother deny fever, they affirm nausea and anorexia. The pain is described as a general aching with very infrequent 10-second paroxysms. Your resident anticipates your forthcoming question and affirms mild patient discomfort when going over bumps during the car ride to the hospital and then—as you anticipate for any resident caring for children—states that she asked the patient about constipation. The response: “I go every day.”

Just as you begin to place your hands on the patient to conduct your own brief abdominal exam, the radiology technician arrives to transport your patient to CT. Fighting the tendency to “go with the flow,” your conscience (and possibly some righteous indignation) causes you to say, “I need another 10 minutes.”

Since your patient is not all that thin and has already been examined a few times, palpating her abdomen is a challenge. She does, however, continue to express considerable tenderness in response to right lower quadrant palpation. However, her maximal tenderness is experienced only slightly lateral and caudal to the umbilicus and not at McBurney’s Point (figure 1 below) [1]. Moreover, there is no rebound tenderness. Adjunctive tests such as those for obturator and psoas signs are negative. It is past time for ultrasound.

Ultrasound demonstrates reasonably active peristalsis in multiple small bowel loops that are easily compressible and much larger in diameter than either a normal or diseased appendix. Moreover, there is no significant hyperechoic soft tissue in the right lower quadrant.

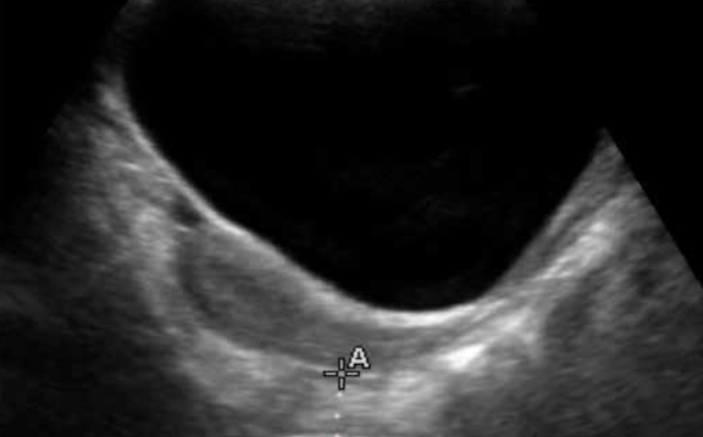

You move your probe to the supra-pubic area and using the partially filled bladder as an acoustic window, you visualize the rectum. It appears to be approximately 2½ cm in diameter (Figure 2 above). Rotating your probe to the transverse position, you notice marked concavity of the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 3 below). Tracing “upstream,” you follow the sigmoid to the ascending colon and notice that the content remains solid considerably further toward the splenic flexure than to what you are accustomed.

Trying to combine palpatory skill with what you’ve observed using ultrasound, you now attempt to hone-in on the precise “point-of-maximal tenderness” described earlier. As a result of the synergy between ultrasound and physical exam, you appreciate what you believe to be hard stool slightly to the right of the patient’s midline at the PMT. Anatomically, this represents a distended sigmoid colon resulting from the accumulation of hard stool.

Your resident volunteers to order a confirmatory abdominal x-ray, but you have seen (and felt and heard) enough. You order your institution’s pediatric enema of choice and wait for word on the outcome. As you anticipated, the enema you ordered “produces” a considerable amount of hard stool and, most important, is associated with complete resolution of your patient’s abdominal pain.

In order to protect your resident, you decide to make the call-back to the referring PCP yourself. He is a little worried that you are being zealously minimalistic in regard to avoiding radiation, but agrees to talk with the mother by telephone. She makes a convincing argument that her daughter’s abdominal discomfort has fully resolved. You prescribe a one-week course of a popular stool-softener and advise a change in bathroom habits, particularly as they relate to her school schedule. The patient does well and the family sends you a thank-you note a few months later.

Teaching Points

- To be a competent pediatric provider, one must be able to manage the inglorious condition of constipation. Although most families are aware of the need for dietary fiber, there is considerable lack of appreciation for the consequences many of our children experience as a result of their reluctance to use the bathroom while at school. “Withholding” causes desiccation of stool as protracted time in the colon results in greater reabsorption of water. We’ve particularly noticed this in the autumn months when students are re-adjusting to a new environment or classmates, preoccupied, and/or otherwise uncomfortable with the vulnerability that accompanies the use of a school bathroom.

- A frequently useful strategy reorders the child’s pre-school morning ritual. Instead of eating breakfast immediately prior to leaving for school, we advise doing so immediately following awakening, followed by all other morning tasks such as showering, dressing, completing homework, and so on. The premise is that the gastro-colic reflex will facilitate a bowel movement while still at home and prior to the student’s leaving for school.

- It should be mentioned that the differential diagnosis of right lower quadrant pain includes a number of important conditions. In addition to appendicitis, the prudent clinician should also include its mimickers such as mesenteric adenitis, right ovarian pathology, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, urinary tract infection and/or renal calculi. Right-lower lobe pneumonia, Meckel’s Diverticulum, Ascaris lumbricoides, Yersinia Enterocolitica, Mittelschmerz and omental torsion are other considerations.

- Perhaps nowhere is the synergism of clinical judgment and ultrasound skill more useful than in the child with abdominal pain. A low pre-ultrasound probability for appendicitis combined with a sonographic evaluation that reveals neither a distended appendix or signs of peri-appendiceal inflammation should prompt consideration of other conditions as opposed to immediate default to CT scan.

- It should also be mentioned that in smaller and slender children constipation might be suspected following the palpation of a very characteristic hard tubular mass within the ascending colon. Although arguably redundant, we have found ultrasound in these cases to teach pattern recognition which is subsequently applicable to larger children in whom diagnosis via palpation is more difficult.

- There are numerous ultrasound findings that have been associated with constipation. Figure 3 illustrates the characteristic crescent sign where stool within the rectum compressed the posterior bladder wall. Other parameters include increased rectal diameter as measured through the acoustic window of the bladder (Figure 2). The rectopelvic ratio attempts to adjust for patient size and utilizes the tape-measure distance between the anterior superior iliac spines as the denominator (Figure 5 below).

- The addition of ultrasound to clinical impression also optimizes the “staged” diagnostic approach to the dilemma of pediatric right lower quadrant pain. Many agree that a high pre-test probability for appendicitis during clinical assessment coupled with a characteristic ultrasound provides excellent specificity for appendicitis and precludes additional imaging. Conversely, the use of ultrasound early in a staged evaluation may point to other diagnoses and, similarly, avoid the radiation imparted by CT.

- A very important point is that not all “right-lower-quadrant pain” is equal. In the present case, characteristic historical features such as migration from a peri-umbilical site of origin and a non-paroxysmal progression were denied by the patient and her mother. Another atypical feature was presence of point-of-maximal tenderness at a considerable distance from McBurney’s point. Traditional teaching places the PMT of appendicitis as occurring 2/3’s of the distance from the umbilicus to the anterior superior iliac spine as represented in Figure 3. Although certainly not without exception, the location of our patient’s PMT near the umbilicus was more suggestive of constipation due to recto-sigmoid distention.

- Although abdominal radiography has long been a popular test for the diagnosis of constipation, we favor ultrasound for a number of reasons. Ultrasound provides “live video” that can be performed by the patient’s clinician in a timely manner at the point-of-care. It can determine the solidity versus liquidity of intestinal contents with much greater clarity than plain radiography. When combined with the sonographer’s appreciation of brisk intestinal peristalsis, a determination of distal stool liquidity versus solidity can also make the diagnosis of a not-yet-manifested enteritis that will soon manifest as diarrhea.

- One caveat is in order. Constipation, as we know, is more of a first-world condition. In developed countries, normative measures of various colonic diameters occur in the context of a typical western diet. In less-developed countries, norms for stool bulk and intestinal dimensions may be considerably greater [2-4].

- We frequently hear the contention, “but I go every day,” as was voiced by the patient in our scenario. It is also true that individuals who commute using urban freeways eventually make it home every day. However, it is often not without considerable delay and difficulty—an analogy we’ve found to be instructive for patients and their caregivers.

- Although most cases of pediatric constipation are amenable to the conservative strategies used in our case presentation, there are occasions when endoscopy is useful to facilitate satisfactory evacuation. In children suffering from severe and chronic constipation associated with neuromuscular disease, the fluoroscopically guided creation of a percutaneous ostomy facilitates periodic colonic irrigation and may markedly improve quality of life for both the affected child and his or her family.

1 Comment

Do you have a reference article for the rectopelvic ratio to adjust for patient size?