Why watching for the OCR becomes a critical reflex.

A 22-year-old male presented to our community ED with a facial injury after an assault to his face. He stated he was in an altercation with another individual during which he took repeated hits to his left eye with a steel pole, approximately four-hours prior to arrival. The patient did not lose consciousness and could recall the entire event. He was able to run away and was brought to the ED by a friend. Associated symptoms included diplopia, photophobia, blurry vision and significant edema to his left eye.

Vitals on arrival to the ED: 98.8 °F, blood pressure of 141/62 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, 86 kg, and 100% pulse ox on room air. Physical exam is notable for a patient in mild distress secondary to the pain. His left eye exhibits chemosis, periorbital swelling and injected conjunctiva. He is unable to open his left eye without assistance. A small amount of bleeding is noted at the lateral canthus with additional abrasions to his left mandible and nasal bridge. Visual acuity was notable for 20/20 OD and 20/50 OS. Intraocular pressures (Tonopen) were 15 OD and 17 OS. CT of the head and cervical spine without intravenous contrast was unremarkable.

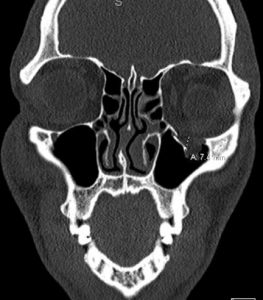

CT of the facial bones without intravenous, image A and B, revealed a comminuted fracture (blowout) of the left infraorbital wall with up to 7 mm of displacement of the fracture fragment into the left maxillary sinus, with orbital fat seen entering the left maxillary sinus through this defect. There is no definitive involvement of the extraocular muscle tissues, although the fracture is near the left inferior rectus muscle with associated intraorbital air. The radiologist recommended clinical correlation for evidence of extraocular muscle entrapment.

During the course of his ED stay, the patient’s heart rate would fluctuate from 92 beats/min to sinus bradycardia as low as 36 beats/min and hypotension to 86/48 mmHg with attempted upward gaze, consistent with a positive oculocardiac reflex. Given these findings, the patient was transferred to a tertiary hospital for surgical intervention with ophthalmology and oculoplastic surgery as there was clinical evidence for extraocular muscle entrapment. The patient was taken to the operating room about three hours later where he underwent left orbital floor fracture repair with entrapment release. He had an uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on day 2. At his two-week ophthalmology follow-up visit, the patient has 20/20 visual acuity, no diplopia, no signs of glaucomatous disc disease, normal intraocular pressure and full extraocular movements.

Discussion:

The oculocardiac reflex (OCR) is an infrequently taught reflex in emergency medicine, however, it is a critical reflex worth reviewing. In patients presenting with significant maxillofacial/orbital injury, the OCR presents as significant bradycardia and hypotension, which can lead to syncope.[1] The OCR is regularly reported during strabismus surgeries involving traction on extraocular muscles. In the trauma setting, the OCR is encountered with fractures associated with entrapment of extraocular muscles or pressure on the globe (intraocular hypertension). The ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve functions as the afferent loop to the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and brainstem. The result is a vagal response with attempted upward gaze.[1,3]

Signs and symptoms of an orbital floor factures can include: hypoesthesia within the V2 distribution (infraorbital nerve damage), vertical diplopia, orbital pain and enophthalmos (posterior displacement of the eye). Other signs depending on the injury can also include ptosis, mydriasis, ecchymosis and subcutaneous emphysema.[5]

One clinical presentation within the medical literature of a positive oculocardiac reflex included one patient with a complete orbital wall fracture that presented with significant autonomic instability with bradycardia down to 20, periods of asystole and hypotension requiring inotropic support.[1] The risk of fatal arrhythmias has been reported in 1 in 3,500 patients presenting with an OCR.[2] Asystole and sudden death have been seen in isolated maxillary trauma, mandibular trauma, zygomatic fractures and severe periorbital lacerations secondary to this reflex.[3]

Releasing the entrapped extraocular muscle is imperative for functional recovery. In one study, hypoxia of the entrapped inferior rectus muscle was encountered about seven hours from the initial injury. One patient presented with a nondisplaced orbital floor fracture with only minimal soft tissue herniation. This patient was subsequently taken to the OR three days later and ischemic necrosis had already set in.[2]

This indicates that immediate recognition and repair is of paramount importance. In our patient, the facial CT showed no definitive involvement of the extraocular muscle tissues, but did show orbital fat entering the left maxillary sinus tissue. However, given his clinical presentation and physical exam with a positive OCR, there was concern for extraocular muscle entrapment.

Further, while isolated maxillofacial/orbital injury would make for better recognition of the OCR, the patient presenting to the ED as a polytrauma could pose a challenge to the clinician as the focus may be initially on resuscitation and stabilization, with multiple reasons for potential bradycardia, hypotension and syncope. Additionally, concomitant cerebral edema along with significant ocular trauma could pose a challenge. A patient with cerebral edema secondary to intracranial pathology along with ocular trauma could present to the ED with a bradycardia and a fixed and dilated pupil as a result of the OCR.

At first, the patient may appear to have raised intracranial pressure and need for immediate neurosurgical intervention, however, acute traumatic glaucoma can induce an OCR that could appear to mimic the Cushing’s reflex (increased blood pressure, irregular breathing and bradycardia).[4] Since facial trauma and head trauma often coexist, watching for the OCR becomes a critical reflex.

In all of these cases, attention to the history and physical is important. A patient presenting with bradycardia, nausea, hypotension and/or syncope in the setting of orbital injury should undergo a CT scan. If there is evidence for incarceration of soft tissue, they should undergo fracture reduction and release of entrapped tissue the same day, preferably within a few hours. In our patient, rapid recognition of the OCR and evidence for entrapment was vital as we did not have ophthalmology in house for surgical intervention and required transfer to a tertiary center.

The University Of Iowa Department Of Ophthalmology recommends immediate surgery within a few hours in these cases.[5] If extraocular entrapment is not recognized and/or surgery is delayed, the result can be ischemic necrosis, permanent restrictive strabismus and life-threatening arrhythmias.[2]

References:

- Pham, C, Couch, S. “Oculocardiac reflex elicited by orbital floor fracture and inferior globe displacement.” American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports. 2017 Jun; 6: 4-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5722179/

- Sires, B, Stanley, R, Levine, L. “Oculocardiac Reflex Caused by Orbital Floor Trapdoor Fracture: An indication for Urgent Repair.” 1998;116(7):955-956. JAMA network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/262873

- Fahling, J, McKenzie, L. “Oculocardiac reflex as a result of intraorbital trauma.” The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 557-558, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27727041

- Levine, J, Bisker, E, Galette, S, Kumar, M. “The Oculocardiac reflex may mimic signs of intracranial hypertension in patients with combined cerebral and ocular trauma.” Neurocritical Care. February 2012, Vol. 16, Issue 1, pp 151-153. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21607785

- Rixen, J, Call, C, Carter, K. “White-eyed blowout fracture.” January 11, 2012. University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/145-white-eyed-blowout-fracture.htm