The great masquerader strikes again.

It’s a typical busy Monday afternoon when you sign up to see your next patient, a 78-year-old woman with back pain. As you walk in the room, you see an elderly woman sitting on the stretcher and talking to her family. She turns and says with a strained smile, “Oh, hello dear. I’m sorry to be such a bother, but my back has been hurting me.”

You pull up a stool and ask some more questions. She tells you that she has had pain for about one week. It started in her epigastric region initially and radiated to her back, but she has only felt it in her back today. Her pain has been constant and has overall been getting progressively worse, but has a waxing/waning intensity. It is currently 8 out of 10, dull and aching.

Nothing seems to make her pain better or worse, including eating or drinking, taking acetaminophen or ibuprofen, or position. There is no associated nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, urinary symptoms, chest pain, dyspnea, cough or fevers. Her medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation and arthritis. She laughs when you ask about social history and denies tobacco, alcohol and drug use.

Her vital signs include blood pressure 111/45, heart rate 95, temperature 37°C, respiratory rate 21 and SpO2 95% on room air. On exam, she appears uncomfortable, but pleasant and cooperative. She has an irregular rhythm, clear lungs, intact strength and sensation, clear speech, and no peripheral edema. When you palpate her abdomen, she winces and has some voluntary guarding. When the patient relaxes, you are shocked when you feel a pulsatile mass in her epigastrium.

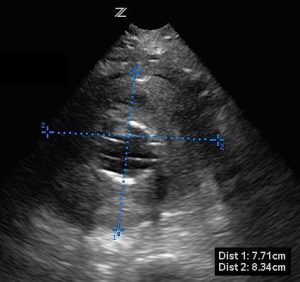

You excuse yourself briefly to track down your ultrasound machine and return to the room. When you place the probe on the abdomen, you see:

Transverse view of proximal aorta with large AAA, approximately 8 cm diameter.

You explain to the patient that you are concerned she has an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and point out the structures on the screen. Looking concerned, she says “I think my mother died of that.”

You step out of the room to order labs, medications and to page vascular surgery. They review your images and agree the patient has a symptomatic AAA. They request a CTA and plan to take her to the OR for endovascular repair.

PEARLS/PITFALLS:

- How do I scan the aorta?

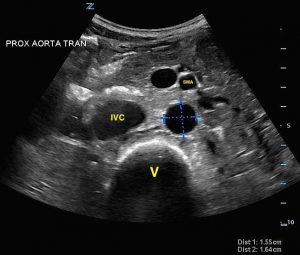

Start in the epigastrium with a curvilinear or phased array probe held perpendicular to the abdominal wall. Look for a transverse, or short, axis of the aorta and then a sagittal, or long, view. The aorta can be identified as a round pulsatile vessel sitting above the vertebral body just left of midline. The spinal bones appear very bright and curved with posterior shadowing (see images 2, 3). Frequently, the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) can be seen branching off the proximal aorta. It should be distinguished from the inferior vena cava (IVC), which travels through the liver, has a hepatic vein draining into it just distal to the diaphragm, and then empties into the right atrium. The aorta travels below the liver and sits on top of the vertebral bodies; it has no branches in the liver.

Next, follow the aorta down through the middle aorta in real time to ensure no abnormalities until you find the distal aorta. Visualize the distal aorta in both transverse and sagittal planes. The last view is of the bifurcation of the aorta into the iliac arteries.

Normal measurements are up to 3 cm in diameter for the abdominal aorta and up to 1.5 cm diameter for the iliac arteries. Measurements should be taken in the transverse plane of both the proximal and distal aorta for the most accurate dimensions. Up to 20% of AAAs extend down through the iliacs and isolated aneurysms can be present in up to 7% of cases. If the iliacs appear abnormal, measure them!

- Normal view of transverse proximal aorta with labels.

- Normal view of sagittal proximal aorta with labels.

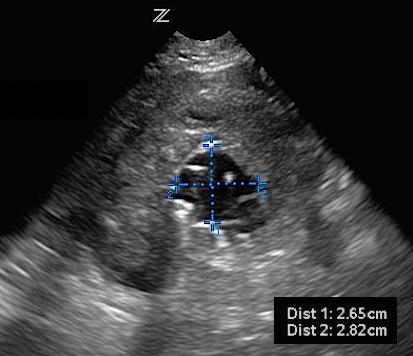

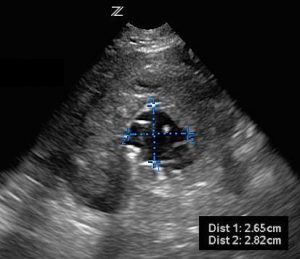

- Measure outside wall to outside wall in two directions

It is extremely important to measure from outer wall to outer wall of the aorta. If just the lumen is measured and a thrombus is not recognized or included, this can give a falsely normal diameter. Any thrombus surrounding the lumen needs to be included in the measurements (see images 4, 5). A true diameter can give a significantly different measurement that may change the management of the patient.

- Transverse view of aorta with incorrect measurement of lumen.

- Transverse view of aorta with correct measurement of lumen, thrombus included.

- Ultrasound can rule out AAA

A systematic review published in Academic Emergency Medicine evaluated how well bedside emergency ultrasound compared to other diagnostic modalities, including radiology ultrasound, CT, MRI and autopsy. The authors found that emergency physicians had a 99% (95% CI 96-100%) sensitivity and 98% (95% CI 97-99%) specificity. They concluded that when EPs obtain adequate images of the abdominal aorta, we can rule out an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- Look in Morison’s Pouch, but many AAAs rupture in the retroperitoneum

As with other diseases with potential free fluid, look in the right upper quadrant if you are concerned the AAA has ruptured. Many aneurysms rupture into the retroperitoneal cavity, so an EFAST study might be negative, but a quick ultrasound to look for free fluid can answer a question quickly and at the bedside of an unstable patient.

- Troubleshooting

Bowel gas can obscure your images. Try applying gentle pressure and fan your probe back and forth to see if this can induce peristalsis and reveal a better view of your aorta. The patient can also be repositioned onto their left side. If you’re having trouble visualizing the bifurcation because of the umbilicus, you can try to fill the bellybutton with gel or scan from below/above/to the side of the umbilicus and angle your probe towards it.

References:

- Rubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, et al. Systematic review: emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm.Acad Emerg Med 2013; 20:128-138.

- Noble VE, et al. Emergency and Critical Care Ultrasound. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Ma OJ, et al. Emergency Ultrasound. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2008.