A patient complains of severe pain in her thigh despite no significant external symptoms. A bedside ultrasound, and plenty of compassion, reveals the underlying issue.

“I’m so sick of these drug-seekers. Another one just got placed in room 24. Why can’t we just treat ‘em and street ‘em?” You turn around to see what the ruckus is all about and see a group of your veteran nurses commiserating at the desk. It’s been a long day already with multiple patients coming in with allergies to morphine and Toradol. Many have requested “that drug that starts with a D” and some were savvy enough to ask for IV Phenergan with it.

Compassion fatigue has hit your department hard today, and you can tell your staff is pretty apathetic and detached at this point. Understanding how easy it can be to be lured into the gloom and doom, you purposefully overcompensate and walk briskly into the patient’s room – eager to help and address her pain.

“I’m going to help get you feeling better, ma’am. Can you please tell me what has been going on with your leg?” Your caring and compassionate introduction is met with moaning and wailing. The young lady in front of you is clutching at her thigh and can barely answer your questions in between her cries of pain.

“I can’t stand it anymore! The pain is 20 out of 10. Stop asking me so many questions and give me some pain medications!!”

You take quick note of her vitals: HR 120 bpm, BP 156/70, RR 22, oxygen saturation 100% and temperature 37.6°C in triage. A quick head to toe survey doesn’t reveal anything grossly abnormal, but you are having a difficult time getting much information out of her because she continues to cry and yell at you in pain. She is aggressively rubbing her medial thigh while you patiently attempt to get a history from her. She has had pain and redness of her left thigh for the past 24 hours. There has been no trauma and she has never had anything like this before. She has no past medical history and she is not taking any medications.

With some gentle coaxing, you are able to get your nurses to come in and start a peripheral IV so you can give your patient some pain medications and perform a thorough evaluation of her thigh. You aren’t sure if the patient is overacting and being hysterical or if she is truly having excruciating pain in her extremity. In situations like this, you know it’s better to be safe than sorry, so you opt to give her 0.1 mg/kg of IV morphine and have your nurses draw and hold a rainbow of blood tubes just in case.

After the IV morphine, your patient appears to be a little calmer, but she is still complaining of 10 out of 10 pain. On closer inspection of her thigh, the medial aspect is erythematous and warm to the touch, but there are no breaks in the overlying skin, and you don’t palpate any fluctuance, induration or crepitus.

Because the patient is obese, and you haven’t been able to elicit much information from her, you decide to augment history and physical exam with a bedside, focused ultrasound of her thigh.

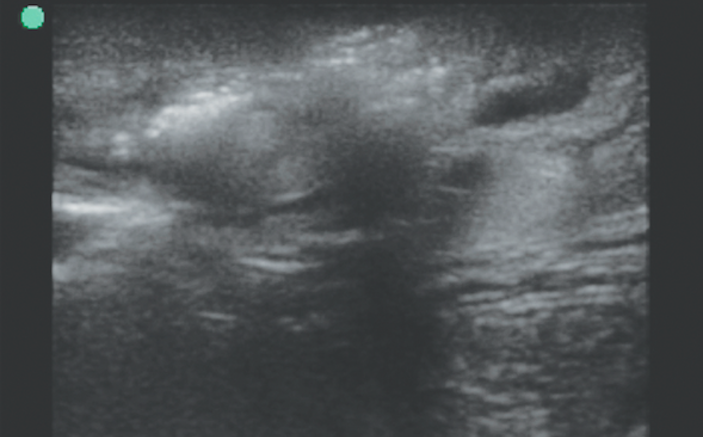

You ask the patient to point with one finger to where she is having the most pain and you start by placing your high-frequency linear transducer right over that site. You obtain a few views of her inner thigh. What do you see? What is your next step in managing the patient? (Slide the second image back and forth to see explanations)

[twentytwenty]

[/twentytwenty]

You realize immediately that there is more than meets the eye in regards to this patient. On your point-of-care ultrasound, you can see hypoechoic, black fluid surrounding the soft tissue and percolating in between the underlying fascia and muscles of her medial thigh. What you find most concerning, though, are the bright white, hyperechoic speckles that suggest that there is subcutaneous air or gas forming in her soft tissue. The air trapped in her soft tissue is causing a dirty acoustic shadow behind each pocket of gas and preventing you from clearly visualizing the underlying soft tissue and muscle. Her fascial planes look a bit thicker than normal and the muscle you are able to visualize appears disrupted and inflamed.

Given her signs, symptoms, and ultrasound findings, you decide to call your surgery friends to expeditiously evaluate the patient for operative intervention and debridement. You send off a CBC with diff, CMP, lactate, serum hCG and blood cultures, and start broad spectrum IV antibiotics immediately, meanwhile aggressively treating her pain and discomfort with IV narcotics.

Your surgery colleagues agree with your diagnosis of a necrotizing soft tissue infection and while they are getting her ready for the OR, the patient’s labs come back. Not surprisingly, she has a profound leukocytosis and a lactic acidosis. You hang more IV fluids and help expedite her transfer to the operating room.

Hours pass and your shift starts to wind down. After that case, your team appears humbled and everyone made a concerted effort to perform an emotional and personal reset.

“Doc, I’m sorry I was being so judgmental with that lady. I just thought she was being melodramatic. What happened to her leg?” You give your nurse a pat on the shoulder and tell him that compassion fatigue happens to the best of us. “The patient had about 12 x 6 inches of her medial thigh debrided for necrotizing, flesh-eating cellulitis, but she is awake from her surgery and expected to recover well with aggressive antibiotics and a new transplanted flap. We should be proud that we didn’t let our internal biases and emotional negativity blind us to what the patient really needed from us. Now go eat some food, get some rest and find healthy ways to combat that compassion fatigue.”

Pearls & Pitfalls in Performing Soft Tissue Ultrasound

- Point-of-care, bedside ultrasound can be used to help diagnose cellulitis, phlegmon formation, an abscess, myositis, and necrotizing soft tissue infections.

- Start your soft tissue ultrasound with a high-frequency linear array transducer and apply a copious amount of gel onto the skin. This will allow you to visualize the superficial layers with the highest amount of resolution.

- Start your scan by visualizing either the contralateral normal side, or normal surrounding tissue to establish your baseline. Visualize what normal skin, fascia, soft tissue, and muscle appears like on your patient.

- Then, direct your scan to the area of interest and note any collections of hypoechoic fluid or edema. Make sure you scan systematically through the target structures in at least two orthogonal planes.

- To visualize deeper structures, switch to a lower frequency curvilinear or phased array transducer for deeper penetration. Remember that you’ll be able to visualize deeper structures at the expense of resolution.

- Color Doppler can be applied over the area of interest to see if there is any hypervascularity, inflammation and increased flow.

- If you see collections of bright white hyperechoic speckling throughout the skin, underlying tissue or fascia, scan carefully through these areas of concern. These hyperechoic regions are pockets of gas that will reflect your sound waves and demonstrate dirty acoustic shadowing and some reverberation artifacts farfield to the gas.

- Necrotizing cellulitis and deeper seeded necrotizing fasciitis is often secondary to a polymicrobial infection, and may be due to the presence of invasive, gas-forming organisms. The presence of subcutaneous or deeper seeded pockets of air on bedside ultrasound should heighten your clinical suspicion of a necrotizing infection being present.

- To become proficient and comfortable with point-of-care ultrasound, there is no substitute for hands-on practice and scanning as many patients as you can on a regular basis. The more you see, the more you will know.

- Stay up-to-date on the most recent point-of-care ultrasound advancements and educational opportunities by visiting www.SonoSupport.com.