Incomplete gastro-cutaneous fistula presenting as focal cellulitis following Billroth II procedure.

Background

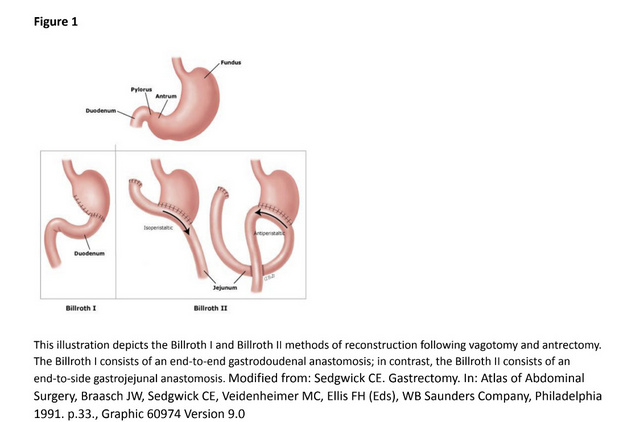

As part of the Billroth II procedure following antrectomy for ulcer disease or tumor, the remnant

stomach is anastomosed to the proximal jejunum (figure 1), preserving jejunal but not duodenal

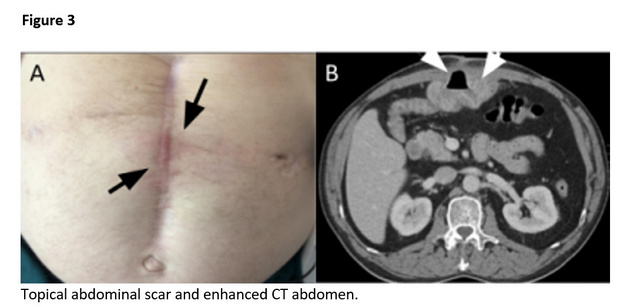

continuity. This end-to-side attachment can be performed in an antecolic or retrocolic, isoperistaltic, or antiperistaltic manner (figure 2). [1]

Studies of the potential differences of the functional, nutritional, and structural outcomes of the individual attachment methods are not available. Lack of duodenal continuity following the Billroth II procedure can lead to impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.[2]

Patients may also experience alkaline reflux gastritis and gastric dumping following reconstruction. [3] Structural complications of a Billroth II procedure also includes formation of enterocutaneous or

gastrocutaneous fistulas.

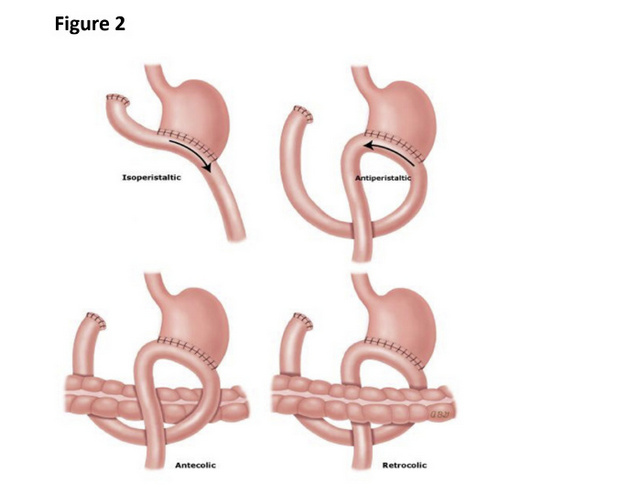

Fistulas can be complete or incomplete which defines a fistula open on two ends or fistula open only on one end. It is thought that these abnormal connections are the result of recurrent gastric leakage and the local inflammation this causes. While larger fistulas are easily identifiable with exploratory laparotomy (figure 3), small fistulas along the abdominal surgical scar may be overlooked.

Variations of Billroth II reconstruction. Modified from: Sedgwick, CE. Gastrectomy. In: Atlas of Abdominal Surgery, Braasch, JW, Sedgwick, CE, Veidenheimer, MC, Ellis, FH (Eds), WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia 1991. p. 33.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old male with past medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nicotine dependence, anxiety, polyarthritis, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of an increasingly painful upper abdomen midline scar. The pain had started 8 months earlier and had become more bothersome over the prior month.

The patient reported that pain was intermittent but when present, was sharp, lasted for hours, and improved with food. The upper half of the surgical scar had become red and tender starting three weeks earlier (figure 3). There was no dehiscence or discharge from the healed surgical scar.

He had a history of constipation and reported having a normal bowel movement three days earlier. A complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, amylase, lipase and lactate, were within normal limits. A CT of the abdomen showed inflammation and thickening at the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis with partial herniation of bowl into the anterior abdominal wall with associated focal inflammation (figure 3).

Eighteen months prior, he was found to have a perforated gastric ulcer and underwent an open Billroth II gastric ulcer repair at that time. Following surgery he was prescribed omeprazole, which he stopped taking seven months earlier.

His prior ED visit was eleven months earlier for abdominal pain; no focal skin changes were recorded at that time. He was admitted for inflammation of the jejunum at the anastomosis with the stomach. His symptoms improved with antibiotics and restarting proton pump inhibitor.

Erythema of healed abdominal scar related to the Billroth II procedure with tenderness on palpation (A); Contrast enhanced CT abdomen showing inflammation and thickening in the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis segment of bowel and partial herniation into the anterior abdominal wall, with associated abdominal wall inflammation (B).

Discussion

Following Billroth II procedure, patients are at increased risk for formation of enterocutaneous or gastrocutaneous fistulas. The patient presented here sought medical attention for possible cellulitis at the site of an abdominal scar related to a Billroth II procedure. A physical exam of the abdomen did not show findings consistent with a midline hernia and bowel herniation.

A CT of the abdomen showed an evolving gastrocutaneous fistula which had progressed when compared to findings on a CT obtained eleven months earlier. The CT also displayed findings consistent with inflammation at the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis and the abdominal wall. Medical management focused on reducing inflammation with a proton pump inhibitor and antibiotics. The abdominal erythema improved and ten months following discharge, the patient remains on conservative management with a proton pump inhibitor which has resulted in good symptom control.

Conclusion

Following a Billroth II procedure, enterocutaneous and gastrocutaneous fistulas are a known complication and may present with atypical features that can occur early or late after an operation. The chronicity of the skin complaints, and the late worsening of symptoms in the case presented here, are less consitent with the time course expected for cellulitis.

While literature reports in cases of gastro- and enterocutneous fistulas are more closely associated with drainage, the case presented here suggests that following a Billroth II procedure, atypical complaints at the site of the surgical scar may warrant imaging.4, 5, 6If recognized, medical treatment of gastro- and enterocutaneous fistuals may defer or possibly avoid additional surgical intervention.

References

- Houghton AD, Liepins P, Clarke S, Mason R. Iso- or antiperistaltic anastomosis: does it matter? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996 Jun;41(3):148-51. PMID: 8763175.

- Trapiello Neto V, dos Santos BM, Petroianu A, Barbosa AJ. Alterações da mucosa gástrica na gastrojejunostomia isoperistáltica e anisoperistáltica em rato [Changes in the gastric mucosa after iso and anisoperistaltic gastrojejunostomy in rats]. Arq Gastroenterol. 1999 Apr-Jun;36(2):94-8. Portuguese. PMID: 10511889.

- Berg, P., McCallum, R. Dumping Syndrome: A Review of the Current Concepts of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Dig Dis Sci 61, 11-18 (2016). http://doi-org.ezproxy3.library.arizona.edu/10.1007/s10620-015-3839-x

- P Hollington, J Mawdsley, W Lim, S M Gabe, A Forbes, A J Windsor, An 11-year experience of enterocutaneous fistula, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 91, Issue 12, December 2004, Pages 1646–1651, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.4788

- Hollis A. Thomas, RADIOLOGIC INVESTIGATION AND TREATMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL FISTULAS, Surgical Clinics of North America, Volume 76, Issue 5, 1996, Pages 1081-1094

- Heimroth J, Chen E, Sutton E. Management Approaches for Enterocutaneous Fistulas. The American Surgeon. 2018;84(3):326-333. doi:10.1177/000313481808400313