SEA is as deadly as it is elusive. Here’s a case-based guide to diagnosis and management of this needle in a haystack.

It has been a long, stressful day in the department, as you have managed several patients requiring resuscitation: one sick septic shock patient with intubation and another with congestive heart failure (CHF) requiring BiPAP. You have two patients who were just roomed, finally clearing the waiting room. Room 3 is a 72-year-old male with chronic arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension with new lower back pain one week after a paraspinal steroid injection for his arthritis. His exam reveals spinal tenderness over L2-L5. The rest of his vital signs are normal, and his neurologic exam is normal as well. Room 9 is a 23-year-old female who is a frequent visitor to the department due to chronic abdominal and back pain. Today she is here for worsening pain. You enter the room and find the patient tachycardic, writhing in pain and screaming, “Please give me my dilaudid!” Her vitals include a fever of 100.4 and tachycardia of 110. She refuses to provide other history.

Back pain is a common presentation to the ED, accounting for approximately 3% of all visits. It is usually classified as acute nonspecific back pain, essentially a wastebasket term for back strain/sprain, mechanical back pain, and lumbago [1-3]. Up to 95% of patients with back pain have no significant pathology and will improve in 4-6 weeks; however, several diseases associated with back pain can cause significant mortality and morbidity [2-4]. Many of the conditions we manage in the ED take into account red flags based on history and physical exam, and one of these is the patient presenting with back pain. Key conditions in back pain include cauda equina, pyelonephritis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, mass, fracture, and spinal epidural abscess (SEA).

Classic isn’t so classic…

SEA “classically” presents with spinal pain, fever, and neurologic deficit. However, this triad is present in only 10-15% of cases! [4,5] With an annual incidence of three cases per 10,000 hospitalized patients with any age affected, this rare disease has potentially devastating consequences [5,6]. The disease is due to collection of inflammatory material between the dura and vertebral column, often extending three to five spinal segments in the thoracic and lumbar spine [4-7]. Once neurologic deficits appear, they are often irreversible. Approximately 50% of survivors will have residual neurologic deficits after treatment, including 15% with paresis or complete paralysis [8,9]. The final outcome is correlated with the severity and duration of neurologic deficit before diagnosis and treatment [4,5].

How well do physicians diagnose SEA, and why do we miss it?

The diagnosis is so difficult that most patients have over three ED visits before a diagnosis is made and diagnostic delay occurs in about 75% [5]. An 11-year review from the Northeast Ohio Medical University identified only 106 cases [13]. Compare that to the vast numbers of ED visits for back pain – in North Carolina in 2009 alone there were nearly 125,000 ED visits for back pain (NCDETECT 2009 Annual Report). With these numbers, even with reasonable ED care, most diagnoses are only picked up after multiple ED visits.

While the classic triad is rare [4,5], what combination of findings are most common? Back pain and severe local tenderness to palpation are the most common early findings, 75% and 58% respectively [5]. Many patients often wait to present to the ED, with a mean duration of 5-9 days from initial symptom onset, which means patients present with a wide variety of neurologic deficits [4,5]. These deficits range from focal motor signs along a specific dermatome, paresthesias, pressure sensation, and even complete paraplegia—approximately one third of patients present with neurologic symptoms [4,5].

In terms of workup, laboratory tests have limited specificity and the definite imaging test, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is not always available in the ED.

Back to our two cases…

With these thoughts on SEA, let’s look at our two patients. Room 3 was the 72-year-old male with new pain after spinal injection. Your neurologic exam including gait, motor, and sensory exams were normal. The first aspect of picking up SEA is a complete physical exam. Gait testing, including heel and toe walking, can pick up subtle findings such as weakness in big toe dorsiflexion (L5). If concerns for bowel or bladder deficits exist, obtain a post void residual. A value greater than 100 ml is concerning for spinal cord impingement [2,3]. Next, you go back to room 9 after providing analgesia, but the patient still appears uncomfortable. However, this time she allows you to complete your history and physical examination. She has noticed about 7 days of lower right leg weakness with increasing pain, making it difficult for her to walk. She has felt warm with chills, and by the way, she started using heroin about two weeks ago after quitting several years ago. Your exam reveals significant weakness in the L4 and L5 distribution, and she refuses to ambulate due to pain. She nearly jumps off the exam bed when you palpate her thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

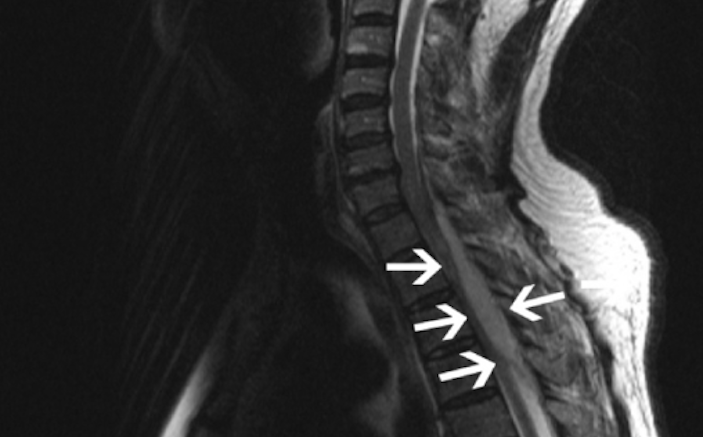

Image 1 displays abscess compressing spinal cord and spinal vasculature.

Image 1 displays abscess compressing spinal cord and spinal vasculature.

Risk Factors and Examination

These patients both have several risk factors, which commonly include spinal instrumentation (including epidural analgesia and paraspinal injection), diabetes mellitus, HIV, trauma, intravenous drug use, immunosuppressive therapy, contiguous soft tissue or bony infection, bacteremia, cancer, renal failure/hemodialysis, alcoholism, and tattoo over the site [4,10,11]. These risk factors reflect the pathogenesis of SEA, as the three most common sources are contiguous infection, hematogenous spread, or iatrogenic. Approximately 30% have no source discovered on investigation. Up to 20% of patients have no risk factors! [7,11]

Despite the presence of multiple risk factors in these patients, they present with different exams, as the older male possesses a completely normal exam while the younger female presents with objective right lower extremity weakness in the L4 and L5 distribution. Early symptoms are non-specific, but they can be broken into four stages: I includes back pain, fever, and tenderness (the 72 year-old male); II includes radicular pain, nuchal rigidity, reflex changes; III includes sensory abnormalities, motor weakness, bowel and bladder dysfunction (the 23 year-old female); and IV includes paralysis [12]. You cannot rely on fever, as approximately two thirds of patients will not have a fever at first presentation [5].

Diagnosis

After your evaluation, you elect to work the patients up similarly with CBC, ESR, CRP, renal function panel, and urinalysis. These tests do not lead to a definitive diagnosis, but they can assist. ESR > 20 mm/h is found in approximately 95% of cases, but no laboratory test is specific for SEA [4,12,13]. Thrombocytopenia (less than 100,000) and ESR above 110 mm/h predict poor outcome [15]. Leukocytosis can be found in 66% of cases, which is insufficient for ruling out the disease [5]. Like the old saying goes, “The CBC is the last bastion of the intellectually destitute!” Blood cultures, positive in approximately 60% of cases [16,17], can help tailor antibiotic treatment, but of course would not be available on the initial ED visit. Thus, empiric coverage is recommended. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common agent, with MRSA and MSSA accounting for about 70% of reported cases with coagulase-negative Staph and gram negative bacilli following [13]. Lumbar puncture is not indicated [4,5,17].

Ultimately, imaging with MRI is required for definitive diagnosis, with sensitivities and specificities above 90% [4,18,19]. Ensure you order gadolinium-enhanced MRI, which allows earlier detection of abscess and prognostication, as increased morbidity exists with central cord stenosis greater than 50% and abscess length greater than 3cm [20]. When ordering the MRI, image the entire spine! Do not just order imaging of the area where the tenderness is present. Skip lesions, or involvement of noncontiguous vertebrae, are common in patients with greater than seven days of symptoms, infection outside of the spine, or elevated ESR at presentation (> 95 mm/h) [21]. If unable to obtain the MRI, your next best bet is CT myelogram which has similar sensitivities, but this test can underestimate abscess length [4,5]. CT with IV contrast is an option, but this test may not distinguish early infectious findings from other changes involving the soft tissues, discs, or vertebrae [4,5,22].

The 72 year-old male has normal laboratory findings except for an ESR of 79, but the 23-year-old female possesses a leukocytosis of 14,000 with neutrophil predominance, along with thrombocytopenia of 82,000 and ESR 120. Luckily, your radiologist and technicians are on top of their games today, and the MRIs of the whole spine are obtained quickly. The 72-year-old male has an abscess over the L4 to L5 region, posteriorly located, but the 23 year-old female has multiple focal fluid enhancements including T1-T2, T10-12, and L3-5.

Management

Once SEA is diagnosed, neurosurgery consultation is required [4,5]. Ultimately, decompressive laminectomy and debridement of the infected tissues should be completed as soon as possible [4,5]. For your two patients, you contact your trusty neurosurgeon on call and relay your concerns and the diagnosis. He asks you to hold antibiotics and obtain blood cultures, as the patients are currently hemodynamically stable.

Treatment regimen is based three factors: 1) neurologic deficit, 2) location, and 3) abscess vs. phlegmon on imaging [8,9,22].

- Patients with developing or worsening neurologic deficits will require surgical drainage (operative versus CT-guided aspiration); however, patients with paralysis upon presentation may be treated with antibiotics alone due to low likelihood of improvement with surgery.

- Abscesses located along the cervical or thoracic region will more commonly be treated with surgery, as greater risk of neurologic sequelae exists. CT-guided needle aspiration in combination with antibiotics is an option for patients with posterior SEA, lack of neurologic deficit, high surgical risk, and no response to antibiotics alone.

- A drainable abscess with purulent material can be drained surgically or by CT aspiration, while a phlegmon with granulomatous-thickened tissue will not benefit from surgery.

Antibiotics are required for management, but they are tailored to cultures from blood and the abscess. After cultures are obtained, broad spectrum coverage should be provided including vancomycin 20 mg/kg IV, metronidazole 500 mg IV, and a third generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime 2 g IV, ceftriaxone 2 g IV, or ceftazidime 2 g IV) [3-5]. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, blood cultures should be obtained and antibiotics with broad spectrum coverage provided.

Of note, improvement should be seen within 48 hours for patients treated with antibiotics alone [23].

Interventional Radiology (IR) should also be contacted, as CT-guided aspiration for patients who are poor surgical candidates is recommended, though this decision should be made in conjunction with neurosurgery. Poor surgical candidates include: those who refuse surgery, high operative risk, paralysis longer than 24 hours, and panspinal infection [4].

Image 2 displays epidural abscess of cervical and thoracic region.

Image 2 displays epidural abscess of cervical and thoracic region.

Outcomes

What most affects outcomes? Half of patients with diagnostic delay and stage III symptoms will have residual deficit, with 15% having complete paralysis or paresis. Mortality can reach rates of 20%, which is more often seen in patients with WBC greater than 14,000, thrombocytopenia, MRSA, prior spinal surgery, corticosteroid treatment, and presence of HIV [5].

Both patients receive antibiotics and go to the OR. The older male due to his comorbidities and location of abscess undergoes CT-guided aspiration. He walks out of the hospital one week later with no deficits. The 23-year-old female undergoes significant surgery with laminectomy over several sites to remove the abscesses. Unfortunately, she experiences some residual weakness of the right leg due to her delayed presentation.

Key Points

SEA often presents insidiously, and the classic triad of fever, back pain, and neurologic deficit is uncommon. The most likely combination of signs and symptoms is back pain and neurologic deficit. The diagnosis is made most often on repeat ED visits, and laboratory findings including WBC are not sensitive enough to rule out the disorder. ESR and CRP will more likely be elevated. A full neurologic exam including gait, motor, sensory, and bladder function can help find subtle deficits, and ultimate diagnosis requires MRI with contrast. Management includes antibiotics and surgical / IR consultation, and final outcome is determined by symptom severity and duration at the time of diagnosis.

REFERENCES

- Strine TW, Hootman JM. US national prevalence and correlates of low back and neck pain among adults. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:656.

- Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain?. JAMA 1992 Aug 12. 268(6):760-5.

- Winters ME, Kluetz P, Zilberstein J. Back pain emergencies. Med Clin North Am 2006;90(3):505-23.

- Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med 2006 Nov 9;355(19):2012-20.

- Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, et al. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med 2004; 26:285-91.

- Sendi P, Bregenzer T, Zimmerli W. Spinal epidural abscess in clinical practice. QJM 2008 Jan;101(1):1-12.

- Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Greenberg SB, et al. Bacterial spinal epidural abscess. Review of 43 cases and literature survey. Medicine (Baltimore) 1992;71:369-85.

- Rigamonti D, Liem L, Sampath P, et al. Spinal epidural abscess: contemporary trends in etiology, evaluation, and management. Surg Neurol 1999; 52:189-96; discussion 97.

- Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev 2000;23:175-204.

- Reynolds F. Neurological infections after neuraxial anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2008; 26:23.

- Danner RL, Hartman BJ. Update on spinal epidural abscess: 35 cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis 1987;9:265-74.

- Heusner A. Nontuberculosis Spinal Epidural Infections. N Engl J Med 1948 Dec;239(23):845-54.

- Shweikeh F, Saeed K, Bukavina L, Zyck S, Drazin D, Steinmetz MP. An institutional series and contemporary review of bacterial spinal epidural abscess: current status and future directions. Neurosurg Focus 2014 Aug;37(2):E9.

- Soehle M, Wallenfang T. Spinal epidural abscesses: clinical manifestations, prognostic factors, and outcomes. Neurosurgery 2002;51:79-85; discussion 6-7.

- Tang HJ, Lin HJ, Liu YC, Li CM. Spinal epidural abscess—Experience with 46 patients and evaluation of prognostic factors. Journal of Infection 2002;45:76-81.

- Gellen BG, Weingarten K, Gamache FW Jr, et al. Epidural Abscess. In: Infections of the Central Nervous System, 2nd Ed, Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Durack DT (Eds), Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia 1997. P 507.

- Curry WT Jr, Hoh BL, Amin-Hanjani S, Eskandar EN. Spinal epidural abscess: clinical presentation, management, and outcome. Surg Neurol 2005;53:364-71; discussion 71.

- Angtuaco EJ, McConnell JR, Chadduck WM, Flanigan S. MR imaging of spinal epidural sepsis. Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:1249-53.

- Wong D, Raymond NJ. Spinal epidural abscess. N Z Med J 1998;111:345-7.

- Tung GA, Yim JW, Mermel LA, Philip L, Rogg JM. Spinal epidural abscess: correlation between MRI findings and outcome. Neuroradiology 1999;41:904-9.

- Ju KL, Kim SD, Melikian R, Bono CM, Harris MB. Predicting patients with concurrent noncontiguous spinal epidural abscess lesions. Spine J 2015 Jan 1;15(1):95-101.

- Pradilla G, Nagahama Y, Spivak AM, Bydon A, Rigamonti D. Spinal epidural abscess: current diagnosis and management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010 Nov;12(6):484-91.

- Hlavin ML, Kaminski HJ, Ross JS, Ganz E. Spinal epidural abscess: a ten-year perspective. Neurosurgery 1990;27:177-84.

- Image 1 illustration derived from Chao D and Nanda A. Spinal Epidural Abscess: A Diagnostic Challenge. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Apr 1;65(7):1341-1347.

5 Comments

Insightful review. Thanks for high-yield clinical pearls.

Really enjoyed writers’ style and presentation. Makes evaluation and management of high-risk disease digestible and clinically useful.

Thoughtfully written and focused. Thank you.

Do you know if there is a survivors group or self help group for SEA? I was 16 and presented with no risk factors in 1985 and know I was very lucky to have survived and walked again.

Thank you for this very well written case! It surely is an important clinical diagnosis and delay can drastically change one person’s life forever.