No available ortho call? With a brief refresher, that shouldn’t be a problem in the ED

Simple interventions for common fractures, such as distal radius fractures, should be within the bread and butter skill set of all emergency physicians. For those practicing in resource-limited environments there is no choice. Distal radius fractures should not be intimidating. Campared with the complexity of other procedures in emergency medicine, reductions are hard to screw up.

The earlier reduction is performed the easier it is to achieve acceptable reduction. Early intervention minimizes risk of expanding hematoma, soft tissue swelling, and muscular spasm which all potentially complicate treatment. When I perform reduction I always document that my involvement represents a more timely intervention, or that I was directed by the orthopedist to perform reduction in order to minimize additional swelling and soft tissue trauma.

Document that you have involved the orthopedist and document concrete physical exam findings which may increase the urgency for reduction such as obvious deformity, skin tenting, change in capillary refill, impending conversion to open fracture, significant swelling, numbness and tingling, or decreased motor function.

Fractures requiring ED orthopedic consultation

When distal radius fractures are not simple fracture patterns, reduction may best be performed in the hands of an orthopedist or hand surgeon. Highly comminuted intra-articular fractures are unstable in anyone’s hands and will require surgery. Obviously any open fracture requires orthopedic consultation as well as any fractures that potentially involve instability of the carpal bones such as dorsal or volar Barton’s fractures in which the carpal bones displace with the fracture fragment. Other complex fractures warranting orthopedics consultation include any pattern of carpal instability manifest by obvious widening of the scaphoid-lunate or luno-triquetral space, or obvious displacement of the lunate suggesting lunate or peri-lunate dislocation.

Variable determinants of treatment

Similar or identical fracture patterns may warrant different treatment in different patients. The most common determinants of care are age, hand dominance, profession, co-morbidities, and activity level. Profession or trade and hand dominance affect tolerance to anything other than anatomic reduction. Older patients with few functional demands can tolerate greater deformity. That said, some older patients, especially those dependent on a cane or walker, may require aggressive interventions to maintain weight bearing through the wrist. Patients with multiple co-morbidities, whether old or young, are less likely to undergo surgical intervention, so achieving near anatomic reductions is more important because reduction is definitive treatment.

Goals of reduction

This brings up another important point. Before reducing any fracture, anticipate the ultimate treatment goal. When orthopedics is involved, I try to get a feel if the intention is ultimately to operate or not. Patients who are unlikely to undergo surgical intervention will require near anatomic reduction.

While anatomic reduction is ideal, some patients will tolerate residual deformity. Obviously musicians, athletes, and anyone dependent on their wrist to make a living or function require minimal residual deformity. Patients who are poor operative candidates can tolerate some displacement, angulation, or shortening. As a general rule though, treat all distal reductions as if they represent definitive treatment. A good reduction in the ED can possibly spare the patient a surgical intervention.

If there is residual deformity or if the fracture remains unstable despite your best efforts, then orthopedic involvement is required. If an orthopedist is on call, this discussion should occur immediately following the reduction so a decision can be made about hospital admission or discharge with followup. If no orthopedist is on call or available, I emphasize to the patient that the best ED treatment has been achieved but additional treatment is needed and an orthopedist should be seen within the next five days.

Functional anatomy of the distal radial-ulnar joint (DRUJ)

Remember the anatomy and biomechanics of the wrist. The radio-carpal joint is responsible for flexion and extension, but pronation and supination, perhaps an even more functionally critical movement, is achieved through complex rotational articulation of the distal radial-ulnar joint (DRUJ). Sometimes we fail to look at the dynamics of the injury. An X-ray provides a static moment in time. Injuries to the DRUJ are often missed or under appreciated and can have far worse functional outcomes then injuries to the radio-carpal joint. If you ever have the luxury of mini c-arm during a reduction, take your next distal radius fracture through pronation and supination under live flouro (while the patient is sedated, of course). The dynamic articulations are astounding. Think about how many daily activities involve pronation and supination: opening a door, turning a key, pulling luggage, lifting a bag off the floor. Shortening of the radius can result in significant disruption of the DRUJ, so achieving appropriate length can be just as important as achieving appropriate alignment. Simply identifying fracture lines that extend into the DRUJ can be an important piece of information that may affect the orthopedist’s threshold to pursue operative intervention.

Procedural sedation and hematoma block

Procedural sedation using propofol, ketamine, or some combination is common. As we have become more comfortable with procedural sedation, the art of hematoma block has been lost. Hematoma blocks can be extremely effective as primary analgesia or an adjunct for patients who cannot tolerate aggressive sedation.

Performing a hematoma block is pretty straightforward:

- Feel with your thumb where the fracture is. It’s typically an easily identified step-off.

- Next stick a needle in right at the fracture or just proximal to it. It’s easy because you just stick the needle in until it hits bone.

- Once you do, start marching the needle toward where you think the fracture line is until you feel your needle drop into the space, usually with a tactile crunch.

- I usually angle my needle to what I think is a similar angle of the fracture line as I march it forward looking for the fracture site. Often the angle needs to be adjusted a few times before you drop in.

- Once in, draw back and you should see very dark blood in addition to what looks like olive oil in your syringe. The olive oil looking substance is fat. When you see this mixed with dark blood, you’re in the right place.

- Inject. It should go easily. You’re done.

A few tips: Doing a hematoma block while hanging the arm in finger traps opens the fracture site and makes it a lot easier. One other thing, a little Ativan goes along ways to mellow patients out before and during the procedure.

Brachioradialis spasm

Think about wrapping a popsicle stick end to end with a tight rubber band. Then break the stick. What happens? The two pieces shorten and overlap under the deforming force of the rubber band. Now try to put the two ends back together, fitting all the jagged edges together while the rubber band is still working against you. You have to fight against the rubber band. This is exactly what happens in any long bone fracture. There are countless muscles whose origin is proximal to the fracture site and insertion is distal. When the spanning muscles spasm, they shorten and deform alignment. The most common muscle culprit in distal radius fractures is the brachioradialis muscle, with the origin above the elbow on the lateral super-condylar ridge and insertion on the radial styloid. Brachioradialism spasm can be somewhat overcome during reduction when the elbow is flexed. You have to fight against this muscle to get the fragment back out to length.

Reduction: Traction is your friend

Often slow gradual traction or even gravity with finger traps is all that is needed to help overcome muscle spasm. The easiest way to achieve traction for distal radius fractures is with finger traps. Hang the patient’s fingers from an IV pole with the elbow near 90 degrees and not resting on the bed. You can also hang a little weight with looped stockinette around the biceps to give some counter traction. Raise or lower the bed to keep the elbow at 90 degrees and slide the patient to the edge of the bed so the elbow is hanging, not resting on the bed. I’ll typically do a quick hematoma block, go see someone else and come back to find an extra 1-2cm of forearm length. It’s important to tell the patient to relax and let the elbow hang (Ativan helps). If you don’t have traps in your department, your OR probably will, since finger traps are used for wrist arthroscopy.

Once you achieve traction and sedation, reduction is essentially a matter of recreating, then reversing, the mechanism of injury. Think: how did this person do this? Falling on an outstretched hand involves impaction and dorsal displacement. So while under traction, dorsally “unlock” the fragment (recreating the injury) then bring the fragment volar (reversing the mechanism).

Remember the periosteum from anatomy? It’s a tissue sleeve that surrounds all bones and provides vascularity. It’s also your enemy in reductions. Often times the Periosteal sleeve remains intact with bone fragments encased within it. If a part of the periosteal sleeve becomes folded and entrapped within the fracture site, all the volar force in the world won’t realign the frag-ments. That’s why traction and recreating the injury with a dorsal “unlocking” move is helpful. Although this briefly exaggerates the existing deformity, unlocking the periosteal sleeve folded into the fracture site can be critical in achieving reduction. For distal radius fractures this involves pulling traction, then slightly bending the dorsal fragment even more dorsal while main-tain traction. After performing this “unlocking move” you reverse the mechanism, and reduce the distal fragment volarly and back out to length, all while maintaining traction.

A common pitfall is over flexing the wrist during reduction. The wrist doesn’t need to be moved, the distal radial fragment needs to be moved. If you bend the wrist a great deal during reduction, you lose all the leverage that should be applied to the distal fragment. I find it helpful to put my thumbs on the distal fragment and then move the wrist so I know how much space I have to work with. The smaller the distal fragment, the harder it is to maintain leverage. Sometimes soft tissue swelling makes it’s hard to know where the fracture site ends and where the wrist articulation begins. Simply identifying these landmarks can be helpful.

When asked how much force I use, the answer is: A lot and as much as necessary. Residents often fail in reduction because they are too hesitant and guarded in their reduction. This isn’t a delicate procedure. You have to stabilize the proximal portion of the radius while leveraging an oftentimes very small distal fragment.

If you’re lucky enough to have mini c-arm fluoroscopy to confirm your reduction, the process is much easier. Because I was trained without fluoroscopy we had to gauge reduction mainly by exam. You can usually tell when you’ve achieved reduction just by looking at the wrist. You also typically feel it key in during the reductions. I usually push the fragment past what I think is needed because those distracting muscles will always undo a little of your hard work. Also, remember that normal alignment of the articular surface of the distal radius is anatomically in 10-15 degrees of volar angulation, so straight is not anatomic alignment. A little past straight is the goal.

Determining stability

It’s important to get a sense of how stable a fracture is when performing reduction. Some fragments seem to key together like puzzle pieces while others seem like a bag of marbles. Instability is the likelihood or tendency that the fracture is going to fall apart after reduction. Remember those musculotendinous distracting forces? They are constantly applying force across the fracture site even after reduction and splinting. Some patterns simply keep falling off. These are much more likely to require operative intervention. Usually you feel it during reduction. Even re-ductions that look perfect can fall apart in the days awaiting orthopedic follow up. When I feel a fracture is unstable I try to communicate this to the orthopedist so plans can be made for surgical correction.

Splinting and immobilization

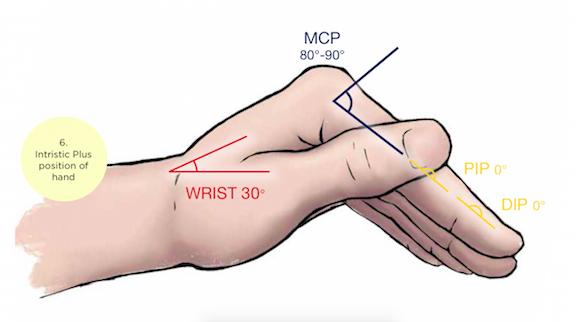

This should be pretty straightforward, but I’m always surprised by how bad splints can be. A few important considerations: First, remember those deforming muscles? There is always one muscle group stronger than its opposing muscle group. This is what results in those horrible contractures we see in non-ambulatory care settings. Because one muscle group is typically stronger than the other, a neutral position is often not a muscularly balanced position. In the hand, the safe position is the “intrinsic plus” hand. It’s not the “beer can” position many of us were taught. The intrinsic plus hand holds the joints in positions which balance and oppose the stronger deforming forces. This is with the metacarpo-phalangeal (MP) joints flexed at 60-90°, the interphalangeal (IP) joints fully extended (not bent like in the “beer can” position) and the thumb is in a neutral projection. The wrist is held in extension typically around 10-30°. For distal radius fractures though, extending the wrist may promote instability particularly in unstable fracture patterns so neutral is common and occasionally 5-10 degrees of flexion can be acceptable. The old hyper-flexed “cotton picking” position is no longer considered acceptable. Nor is the term “cotton picking”. Greater immobilization is achieved with greater splint length on either side of the fracture. That means extending the splint at least to, or slightly past, the MCP joint depending on the stability of the fracture pattern. The more unstable, the more distal I go. Apply Sugar Tong style splints as opposed to volar splints in unstable patterns. Sugar Tongs provide much more stability while still allowing for swelling. I use at least a single sugar tong for every fracture that involves reduction and often a double sugar tong on unstable fractures.

The last consideration is pronation and supination. Remember, the radius flops completely over a fixed ulna thorough supination. There is no question that immobilizing pronation and supination is critical when there is involvement of the DRUJ. Even a subtle crack that’s barely visible passing into the DRUJ can massively displace during pronation and supination. Some hand surgeons argue that all unstable distal radius fractures should be immobilized with double sugar tongs. Although not universally standard of care, I still use this aggressive splinting in young patients with unstable patterns demanding anatomic reductions or involvement of the DRUJ. I’m less aggressive with double sugar tongs in elderly patients likely to develop adhesive capsulitis of the elbow (frozen elbow) so I use single sugar-tongs, which allow some flexion and extension but still limit pronation and supination. Volar splints do not limit pronation or supination.

Patient expectations and follow up

Communication with patients is paramount in predicting patient satisfaction in all aspects of emergency medicine. As with countless ED encounters patients often expect to see a “specialist,” so whenever possible I communicate that a specialist has been involved and that you both agree that a timely reduction by the ED doctor would be the best course of care.

Patients should also get some sense of whether or not ED reduction represents definitive care. Although this is often unknown I try to discuss the variables and determinant of care, which they find helpful in understanding their possible treatment course. When a fracture is obviously unstable I let patients know that we are simply improving alignment before surgery to minimize swelling, soft tissue trauma and the risk of neuromuscular compromise. If I can achieve a stable and near anatomic reduction I still emphasize the possibility that the construct can collapse even in immobilization but there is a chance reduction and splinting is all that will be required. It seems intuitive, but patients should also be informed that splints are designed to allow for swelling and the splint will be converted to a cast at the time of follow up.

Explain the concept of fracture healing. Delaying surgical intervention by a week certainly does not prolong healing time, particularly if adequate reduction has been achieved. Delaying reduction, however, can significantly change the treatment course. If reduction is delayed by days, it is much more likely that a previously non-operative fracture now becomes operative. I also dis-cuss the possible complications of delayed union or non-union especially in diabetics and smokers.

Disposition

Distal radius fractures do not need to be admitted with the following exceptions: They are open, there is neuro-vascular compromise, there is risk of developing compartment syndrome, the patient is unable to function at home, the patient has limitations to outpatient follow up, or the orthopedist simply wants to get an operative case done quickly. Discharged patients should be seen within a week.

5 Comments

In 1972 I had a fracture through the growth plate reduced while awake with only the benefit of cold hydrocarbon spray as analgesia. I was told that the alternative was surgery but because my stomach was full it would require a delay placing me at risk for growth abnormalities.

Did this simply reflect the practice of the times or was some type of better local analgesia available?

2e57p

Daniel, The reality is they could have waited four hours and done some other form of analgesia. The could have also done non-sedating analgesia such as hematoma block which was certainly being used at that time.

Today, we do wait for peoples’ stomach to be empty usually four hours which does not change anything in regards to risk of growth plate injury. The incidence of these injuries affecting growth is around 1/200. Our standards for pain tolerance in 1972, however were very different so this may have been acceptable care. Today I have patients ask me to do shoulder reductions without analgesia so its also highly dependent on the patient.

In 1972 emergency medicine as a specialty was in its infancy so you may not have even been treated by an emergency room doctor. It could have been a family practice doctor moonlighting.

Hi,

I had a distal radius fracture and a broken ulna (wrist), was put in a cast for 2.5 months (3 weeks after fracture, surgery was required and re break had to be done). I was in a full cast for 5+ weeks after the surgery. I was told that i have a very ugly Xray by my hand specialist (physio) but so far everything has come back to normal by the 1 month mark (after cast was taken off, so 9 weeks).

The only thing that has not fully come back and is taking a while is supination 65% (pronation is at 90%). I keep working on all the muscle bellies in my arm and this has helped alot with coming from 25% supination.

I’m wondering what is wrong that my supination is not coming back as quickly, i’m getting pain when i try to push past the 65% that i’m achieving now. I’m hoping someone could help me.

John.

Hey guys,

I just had distal radius fracture

I had surgery then was put in a cast for 6 weeks and recently I got my cast taken off and was given a brace I am going to need the brace for 4 weeks before I will be able to take it off.

I am so glad my arm is getting better and I hope you all have a great quarantine!

Estelle