Droperidol has been used successfully in the emergency department (ED) and operating room (OR) for over 40 years. It has been employed with success for the treatment of headache, nausea, agitation, pain in opiate-tolerance and even the dreaded multidrug-resistant abdominal pain (MDRAP).1,2 Unfortunately, in 2001 the FDA issued a black box warning indicating there was a significant risk of cardiac arrhythmias with droperidol.

In 40 years this versatile drug has gone from panacea to blackbox to shortage

Droperidol has been used successfully in the emergency department (ED) and operating room (OR) for over 40 years. It has been employed with success for the treatment of headache, nausea, agitation, pain in opiate-tolerance and even the dreaded multidrug-resistant abdominal pain (MDRAP).(1,2) Unfortunately, in 2001 the FDA issued a black box warning indicating there was a significant risk of cardiac arrhythmias with droperidol. At the time of the black box warning, droperidol held more than 30% of the market share for antiemetics.(3) After the black box warning was issued, many institutions put restrictions on the use of droperidol or completely removed it from their hospital formularies.(4) The timing of the black box warning became a hot topic for conspiracy theorists. Why did it take over 30 years of clinical use to uncover serious adverse events? Why were there so many case reports submitted simultaneously? The proximity in time of these developments to the release of a new class of patent-protected antiemetics (5HT3 receptor antagonists) trying to take a portion of droperidol’s market share raised skepticism.

When the data behind the black-box warning were reviewed, they were found wanting. Prior to 2000, twenty five million doses of droperidol had been sold, but only 10 adverse cardiac events had been reported to the FDA at doses of 1.25mg or less – and all of these cases involved confounding factors.(5) Additionally, the European studies that the FDA cited in their warning had employed droperidol at doses of 50-100 times the usual doses used in the US. In 2013 AAEM issued a clinical practice statement supporting the use of doses under 2.5mg without ECG monitoring.(6) While extrapyramidal effects (akathisia, dystonia) occur in up to 15% of patients who receive droperidol, this is similar to other dopamine antagonists used in the ED to treat nausea, vomiting and headache and these adverse effects can usually be reversed quickly with the administration of an anticholinergic agent (eg, diphenhydramine or benztropine).(7,8)

After the FDA’s report came under scrutiny, droperidol started to resurface in EDs across the country and some institutions allowed droperidol to be administered to selected populations without extensive monitoring.(9) Once again, droperidol became an important medication in the ED.

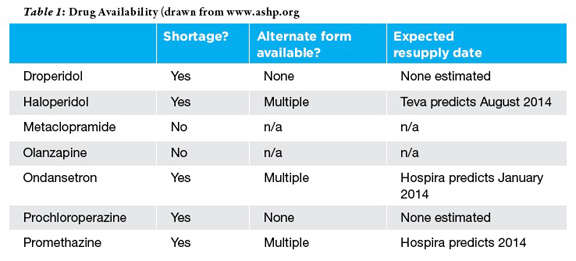

Unfortunately it fell on hard times once again in late 2012 when it appeared on shortage lists and supplies quickly ran out.10 According to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) web-site there are multiple reasons for the continuing droperidol shortage.(10) The two manufacturers who produce the drug (Hospira and American Regent) suspended distribution of their droperidol due to manufacturing delays and shortage of raw material.

Headaches

Accounting for nearly 2.5% of all ED visits, headaches are all too familiar to emergency physicians.(7) Dopamine antagonists (both antipsychotics and antiemetics), opiates and triptans have all been described as potential medications when treating migraine headaches. However, patients presenting to the ED have often already failed a triptan or have a contraindication such as hypertension. Not to mention the multiple reasons to avoid opiates for headache. That leaves dopamine antagonists as many EPs’ first line for treatment of headaches. In head-to-head comparisons (no pun intended), droperidol has proven superior to non-butyrophenone dopamine antagonists such as prochlorperazine. And doses less than or equal to 2 mg have been shown to be effective for headache treatment in the ED.9 Most adverse effects associated with droperidol use are reported as mild to moderate with the prevalence of these increasing with increased doses.(9,11)

Metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and promethazine are all reasonable alternatives when droperidol is not available; unfortunately, these have all been recently listed as on shortage as well. So what do you do if a patient reports that those treatments have failed previously, or you’re unlucky enough for them to be unavailable at your institution? In that case, don’t forget about your other antipsychotics. Both olanzapine (at 10 mg IM) and haloperidol (at 5mg IV) have been found to be effective rescue therapies for ED treatment of headaches.(12,13) While these medicines carry box warnings from the FDA, hemodynamically significant adverse reactions were associated with higher doses than we are recommending or occurred in patients with significant comorbid conditions. Moreover, no adverse hemodynamic events were reported in the aforementioned studies evaluating ED treatment of headache.

Nausea and Vomiting

As with headaches, nausea and vomiting are common chief complaints for patients presenting to the ED, totalling over 8 million visits annually in the United States.(14) Antiemetics have been studied extensively for the treatment of chemotherapy and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The data on droperidol use in the ED for nausea and vomiting is less robust. One randomized controlled trial compared droperidol to metoclopramide and prochlorperazine in patients with moderate to severe nausea.(14) Droperidol 1.25 mg IV was significantly better at nausea reduction compared to metoclopramide 10 mg IV and prochlorperazine 10 mg IV.(14) The results of this trial suggest that 1.25 mg of droperidol is an excellent first line therapy to treat nausea and vomiting in the ED.

With droperidol unavailable, ondansetron, metoclopramide and promethazine are all suitable options for the treatment of nausea and vomiting. Ondansetron, promethazine and prochlorperazine are all still listed on the shortage list but ondansetron and promethazine remain relatively available. Fortunately, manufacturers of metoclopramide do not report any supply issues at this time.(10)

Agitation

Before the black box warning droperidol was a commonly used medication to sedate the agitated or violent patient in the ED. Some articles have even suggested that droperidol is superior to haloperidol or lorazepam, providing a more reliable and rapid response in the agitated patient.(15,16) One retrospective review reported that 5 mg of droperidol was administered 4145 times over a 2.5 year span without a single case report of a clinically significant dysrhythmia.(17) Even with its well-established safety record, droperidol is not FDA approved to treat agitation so using it “off-label” makes it difficult to defend if a serious adverse event should occur.

Unless the black-box warning is removed many will stick with medications such as haloperidol, lorazepam, ziprasidone or olanzapine as their treatment of choice for the acutely agitated or violent patient in the ED – assuming they don’t go on shortage too.

Treatment of Pain In Opiate-Tolerant or Resistant Patients

Patients who chronically use opiates, with or without a valid prescription, often present to the ED in pain. Achieving effective analgesia in these patients can require repeated or high doses of opioids, necessitating prolonged ED stays and close monitoring for respiratory compromise. In such patients, an alternative approach to pain control is desirable. Droperidol is one such alternative. Nociception is a complex process involving dopamine, serotonin and µ-receptors.(18,19) Droperidol appears to act in several ways to promote analgesia – its antidopaminergic properties may augment the response to opioids, its GABA-agonistic effects may inhibit pain transmission, and it appears to enhance both µ-receptor expression and binding in the spinal cord.(20-22) While there are a variety of mechanisms by which droperidol may produce analgesia, what is of greater interest to practitioners is the clinical evidence. Droperidol has also been shown to decrease the required doses of opiates and achieve better pain control in post-operative gynecologic and orthopedic patients.(23,24) Perhaps most impressive to EPs is that droperidol has been successfully used in an ED protocol for pain treatment in opioid-tolerant patients.

If you can’t get the drug, how should you treat pain in opiate tolerant patients? Sub-anesthetic dose ketamine (0.1-0.5 mg/kg) has been shown to be an effective alternative or adjunct to narcotic pain control.(25) While this may not be much help for the issues of drug-seeking and malingering, it does give you a potentially safer and more effective option for pain control in patients with legitimate pain.

Conclusion

At the time of the writing of this article, the manufacturers have stated that droperidol is on backorder and that they cannot estimate a release date. Hopefully this drug with many ED applications will again become available, and in the future the FDA will take a closer look at the data before maligning such an excellent medication.

Dr. Miller is an Assistant Professor and the Director of Medical Simulation for the University of Iowa’s Department of Emergency Medicine. Brett Faine, Pharm D. is a residency-trained Emergency Medicine Clinical Pharmacy Specialist working in the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics’ Department of Emergency Medicine.

References

1. Richards JR, Richards IN, Ozery G, Derlet RW. Droperidol analgesia for opioid-tolerant patients. The Journal of emergency medicine 2011;41:389-96.

2. Have you Seen This New Disease? 2013. (Accessed December 29, 2013, at http://forums.studentdoctor.net/threads/have-you-seen-this-new-disease.1041076/.)

3. Jackson CW, Sheehan AH, Reddan JG. Evidence-based review of the black-box warning for droperidol. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists 2007;64:1174-86.

4. Kao LW, Kirk MA, Evers SJ, Rosenfeld SH. Droperidol, QT prolongation, and sudden death: what is the evidence? Annals of emergency medicine 2003;41:546-58.

5. Ludwin DB, Shafer SL. Con: The black box warning on droperidol should not be removed (but should be clarified!). Anesthesia and analgesia 2008;106:1418-20.

6. Perkins J, Ho J. Safety of Droperidol Use in the Emergency Department: Clinical Practice Statement. American Academy of Emergency Medicine2013 9/7/2013.

7. Richman PB, Allegra J, Eskin B, et al. A randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of intramuscular droperidol for the treatment of acute migraine headache. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2002;20:39-42.

8. Weaver CS, Jones JB, Chisholm CD, et al. Droperidol vs prochlorperazine for the treatment of acute headache. The Journal of emergency medicine 2004;26:145-50.

9. Faine B, Hogrefe C, Van Heukelom J, Smelser J. Treating primary headaches in the ED: can droperidol regain its role? Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:1255-62.

10. Drug Shortages: Current Drugs. (Accessed 12/16/2013, at www.ashp.org.)

11. Silberstein SD, Young WB, Mendizabal JE, Rothrock JF, Alam AS. Acute migraine treatment with droperidol: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 2003;60:315-21.

12. Hill CH, Miner JR, Martel ML. Olanzapine versus Droperidol for the Treatment of Primary Headache in the Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine 2008;15:806-11.

13. Honkaniemi J, Liimatainen S, Rainesalo S, Sulavuori S. Haloperidol in the acute treatment of migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 2006;46:781-7.

14. Braude D, Soliz T, Crandall C, Hendey G, Andrews J, Weichenthal L. Antiemetics in the ED: a randomized controlled trial comparing 3 common agents. Am J Emerg Med 2006;24:177-82.

15. Thomas H, Jr., Schwartz E, Petrilli R. Droperidol versus haloperidol for chemical restraint of agitated and combative patients. Annals of emergency medicine 1992;21:407-13.

16. Chambers RA, Druss BG. Droperidol: efficacy and side effects in psychiatric emergencies. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 1999;60:664-7.

17. Shale JH, Shale CM, Mastin WD. A review of the safety and efficacy of droperidol for the rapid sedation of severely agitated and violent patients. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2003;64:500-5.

18. Wood PB. Role of central dopamine in pain and analgesia. Expert review of neurotherapeutics 2008;8:781-97.

19. Hunt SP, Mantyh PW. The molecular dynamics of pain control. Nature reviews Neuroscience 2001;2:83-91.

20. Tulunay FC, Yano I, Takemori AE. The effect of biogenic amine modifiers on morphine analgesia and its antagonism by naloxone. European journal of pharmacology 1976;35:285-92.

21. Flood P, Coates KM. Droperidol inhibits GABA(A) and neuronal nicotinic receptor activation. Anesthesiology 2002;96:987-93.

22. Zhu CB, Li XY, Zhu YH, Xu SF. Binding sites of mu receptor increased when acupuncture analgesia was enhanced by droperidol: an autoradiographic study. Zhongguo yao li xue bao = Acta pharmacologica Sinica 1995;16:311-4.

23. Sharma SK, Davies MW. Patient-controlled analgesia with a mixture of morphine and droperidol. British journal of anaesthesia 1993;71:435-6.

24. Yamamoto S, Yamaguchi H, Sakaguchi M, Yamashita S, Satsumae T. Preoperative droperidol improved postoperative pain relief in patients undergoing rotator-cuff repair during general anesthesia using intravenous morphine. Journal of clinical anesthesia 2003;15:525-9.

25. Himmelseher S, Durieux ME. Ketamine for perioperative pain management. Anesthesiology 2005;102:211-20.

4 Comments

“The proximity in time of these developments to the release of a new class of patent-protected antiemetics (5HT3 receptor antagonists) trying to take a portion of droperidol’s market share raised skepticism.”

This reminds me of when Nisentyl was taken off the market just at the same time Versed was introduced. Nisentyl was “removed” due to “problems in dental offices.”

Drug shortages, which are now routine, did not occur with anything close to current frequency 20 years ago. This is the pharma industry manipulating the market. If you do not believe that, you are just being naive. Follow the money!

Used this awesome drug in our busy ED without adverse sequelae for nearly 20 years; hospital took it off formulary when black box added. Anyone who has used droperidol knows that there was politics behind the warning, because in experienced hands, extremely safe and almost indescribably effective! This could not have been a clinical decision!

“Just because you’re not paranoid doesn’t mean no one’s out to get you.” (anon)

Strange timing, but it seems the 5HT drugs didn’t become dangerous until they came off patent.

It’s the ancient idea of the sentient drug, which knows the hand that wields it.

Pingback: DROP Drops - Blue Diesel Data Science