Due process should protect physician rights, but it is sometimes used – or waived – to a physician’s detriment.

Hospital management changes. Doctors whose care had never been questioned with the prior administration are now being told that if they don’t see a minimum average of 2.2 patients per hour within the next 60 days, they will be terminated.

*****

A surgeon is hired to replace another surgeon who is scheduled to retire in the near future. The retiring surgeon has a change of heart and decides not to retire. When increasing numbers of referrals go to the new surgeon, the retiring surgeon files several complaints about the medical care provided by the new surgeon. A hearing panel is convened to review the cases. The chairman of the panel is the retiring surgeon’s close friend.

*****

A patient becomes upset with the care provided by an emergency physician and creates a social media campaign against the physician and the hospital. The local news picks up the story. Even though the physician’s care was appropriate, the hospital wants to fire the physician to avoid further adverse publicity.

*****

What protects the physician’s livelihood against scenarios such as these? Due process. At least that’s the idea. Due process is a term we hear often, but what exactly does it mean and how does it protect us? While due process began as a concept to limit the power of government to take action against its citizens, for emergency physicians, due process protections could mean the difference between employment and joblessness or between licensure and unemployability. To understand how due process protections apply, it helps to understand some history behind the concept of due process.

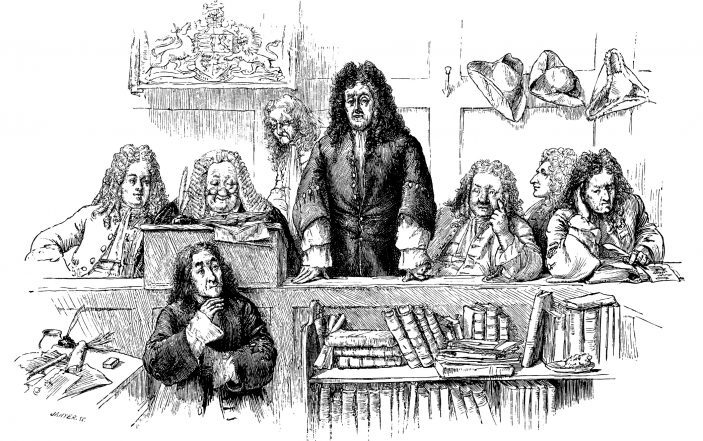

HISTORY OF DUE PROCESS

In the 13th century, the rights of citizens were codified in the Magna Carta. Section 39 of the Magna Carta stated that “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled … except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” These ideals carried over to some degree into British law and were later incorporated into the U.S. Constitution.

The Fifth Amendment requires that the federal government provide due process protections to its citizens while the 14th Amendment extends those same requirements to states and to state actors. In both cases, the Constitution prohibits depriving any person of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

The brilliance in the wording is that it allows courts to interpret what is protected and what protections are required by due process. Protections of “life” generally apply to punishment for criminal acts. Similarly, “liberty” interests usually involve incarceration, but courts have widened the concept of liberty interests to include involuntary civil commitment and involuntary administration of antipsychotic medications. Court decisions have also widened the scope of due process protection to what are deemed “property rights.”

Examples of property interests protected by due process include federal and state employment and retirement benefits, tenure at state educational institutions, entitlement programs, and even licenses. Of note is that in most cases, due process protections do not extend to ordinary employment. In other words, most employees can be fired “at will” – provided that there are no violations of state or federal employment laws when doing so.

MODERN COURT CONSIDERATIONS

The Supreme Court considers medical licenses as “property” for purposes of due process. If a state wants to take adverse action against a physician’s medical license, the physician is entitled to due process before those adverse actions occur. There is no set definition regarding what procedural due process encompasses, but it generally includes a hearing on the merits of the proposed action before a neutral and independent adjudicator, an opportunity to present a defense and to call witnesses, a right to dispute opposing evidence and cross-examine adverse witnesses, and the right to be represented by an attorney.

Even this rule has exceptions. For example, if the state can show that a physician’s practice constitutes an imminent threat to the public, a physician’s license could be suspended immediately pending a hearing on the merits of the case. Since due process applies only to federal or state actors, constitutional due process protections do not necessarily apply to hospitals or to hospital privileges, although even this concept is not absolute. In cases where there is a “mutual expectation of continued employment,” some courts have held that hospital privileges may be a constitutionally-protected property right.

Even in cases where there is no constitutionally-mandated due process applicable to hospital privileges, the Health Care Quality Improvement Act of 1986 outlines procedural safeguards that should be followed during peer review actions, including making “reasonable effort to obtain the facts of the matter” and providing the physician with “adequate notice and hearing procedures … fair to the physician under the circumstances.” Failure to follow these procedures only results in a loss of qualified immunity from retaliatory lawsuits by the physician, and even the Act itself notes that “failure to meet the conditions described in this subsection shall not, in itself, constitute [a breach of the requirements in the Act].”

As a result, hospital bylaws will contain due process protections when adverse actions are contemplated against a physician’s privileges, but there is no standard for what due process protections a hospital must – or should – provide.

APPLICATION OF DUE PROCESS TO PHYSICIAN PRACTICE

Due process only applies when adverse actions are contemplated against a physician’s license or a physician’s hospital privileges. Ostensibly, these protections make it less likely that physicians will have to defend frivolous or petty complaints – and in many cases this is true. However, due process protections can be a double-edged sword. If a hospital wishes to terminate a physician’s privileges, it may use due process procedures to enforce vague or subjective standards against a physician (such as accusations of being a “disruptive physician”), may magnify minor transgressions into actionable offenses, and may allow those with personal or economic conflicts of interest to participate on a peer review committee against a physician.

There are many cases in which hospitals have used “sham peer review” to terminate a physician’s hospital privileges. In most cases, a suspension or termination of a physician’s hospital privileges for matters related to competency or professional conduct must be reported to the National Practitioner Databank. Since hospitals and licensing boards must query the NPDB as part of the credentialing and licensing process, an adverse NPDB report would likely affect the physician’s future credentialing applications, future insurance applications, and potentially even the physician’s medical licensure.

A NPDB report is also mandatory if a physician resigns from the medical staff (or fails to renew privileges) during a peer review investigation. While due process protections may provide physicians with some degree of job security, those same protections could force physicians to hire an attorney and attend multiple peer review hearings in order to avoid being reported to the NPDB – even if the physician has no intention of remaining on staff at the hospital after an investigation.

AVOIDING DUE PROCESS REQUIREMENTS

Any rights, even those granted by the Constitution, may be contractually waived. In order to maintain a quality medical staff while limiting the number of contentious and costly due process hearings, hospitals may require that physicians waive any due process rights contained in the hospital bylaws. Hospitals can also avoid adhering to any applicable due process requirements through contracts with third parties. If a hospital contracts with a staffing company to hire physicians, the hospital may require that the staffing company’s contract with physicians contain a due process waiver. If the staffing company does not agree to the hospital’s requests, then the hospital may choose to contract with another group.

Once a due process waiver agreement is made between the hospital and the staffing company, the group can’t hire a doctor who does not agree to waive due process because it would put the group in breach of its contract with the hospital. A hospital can also avoid due process requirements through requests to its third party contractors. For example, the hospital may simply request that a physician be removed from the staffing company’s schedule. In that instance, there are no adverse actions against the physician’s hospital privileges, and therefore due process is not invoked. The physician still has hospital privileges but is simply not scheduled to work at the hospital.

CONCLUSION

Due process may provide a physician with job security, but the protections afforded by due process are only as robust as their application. Would due process have protected any of the physicians in the examples given at the beginning of this article? If a physician isn’t able to meet the hospital’s patients-per hour goals or the physician causes negative press reports about the hospital, the hospital could threaten an investigation into the physician’s medical care and then offer to accept a resignation before such investigation takes place.

Or, if the hospital contracts with a contract management group, the hospital may simply request that the physician be removed from the schedule. In the case of the surgeon, a peer review hearing took place, the surgeon spent $40,000 defending his care, and the hospital terminated the physician from its medical staff and reported the termination to the NPDB – despite statements from the orthopedist on the peer review hearing panel that the allegations against the new orthopedic surgeon were “baseless” and that the retiring orthopedist was the one whose practice was “negligent.”

Here’s the real problem with due process: It focuses on procedure rather than on the principle or justice. The poor EP struggling to meet a 2.2 pt/hr rate may have to cut corners on patient care. The case involving the surgeon actually occurred. A peer review hearing took place, the surgeon spent $40,000 defending his care, and the hospital ultimately terminated the physician from its medical staff and reported the termination to the NPDB. And finally, the whistleblower – a classic case of kill the messenger. Who gives a damn about the message.

Due process may be intended to protect third parties from taking sudden career-altering actions against us, but sometimes the devil is in the details. Being forced to meet unrealistic patient quotas under the threat of a due process investigation may cause physicians to cut corners on patient care. Defending an investigation may cause a significant financial hardship, in addition to a job loss. If we focus solely on the procedure behind due process and fail to consider the practical effects due process could have on our careers and practice, we may get less protection than we bargain for.

3 Comments

Excellent! After 30 years in the ER, I can say, that often times we are our own worst enemies.

Excellent article. We handle cases which repeatedly confirm the epidemic of due process violations against emergency and other physicians. Your article highlights important themes. I have attempted to bring this knowledge base to the attention of residency program directors on the West Coast–with some limited success. There is a definite correlation between certain character traits and behaviors seen in residency and the propensity to act abusively and inappropriately towards subordinates. Often times, when deposing some of the offending department heads or administrative physicians, it becomes evident that the individual has been encouraged to act abusively, arrogantly and without consequence from their time in residency. Thus, we should be educating residents and attendings on this, and not tolerating conduct or behavior which may be precursors to risky and abusive conduct later.

Dr. Sullivan: It was interesting to find your article and I appreciate your perspective and ultimate conclusion. Just as an “FYI,” in California there is a state law that prohibits a hospital medical staff, medical group or other “peer review body” from waving the due process protections set forth in the state law, specifically including a prohibition “in any instrument” and including bylaws, agreements and contracts, arguably invalidating any effort on behalf of a hospital or staffing company to act as you mention in your article. (Note that, originally the HQIA permitted states to “opt out” and CA chose to implement its own peer review process in the Business & Professions Code. It is unsettled law whether HQIA preempts the CA statutes, but applying general preemption law, more protective rights would likely still apply.)