It’s the end of your shift and you are trying not to pick up any complicated cases when the charge nurse asks you to see a “sick” patient they just put in room 2. You adeptly suppress a sigh and answer “Sure!” with enthusiasm. The patient is in his late 60s and unfortunately has a history of metastatic lung cancer. His wife and son brought him today for gradually worsening dyspnea over the past few days without any fever, cough, chest pain or leg swelling. On exam the vital signs are all normal except for a pulse ox of 92% but he is pale and his breathing is labored with breath sounds that are markedly decreased on the right.

You order a portable chest x-ray which shows an unchanged cardiac silhouette and bilateral pleural effusions with tumor, worse on the right and similar to the last time he had a therapeutic thoracentesis. His CBC comes back normal with no anemia and a duplex of the legs shows no DVT. You don’t see any need to order further imaging even though you know he is at risk for pulmonary embolism, as you have an explanation for his dyspnea, he has no chest pain, and his leg duplex is negative. A D-dimer would be useless as it would almost definitely be positive from the cancer.

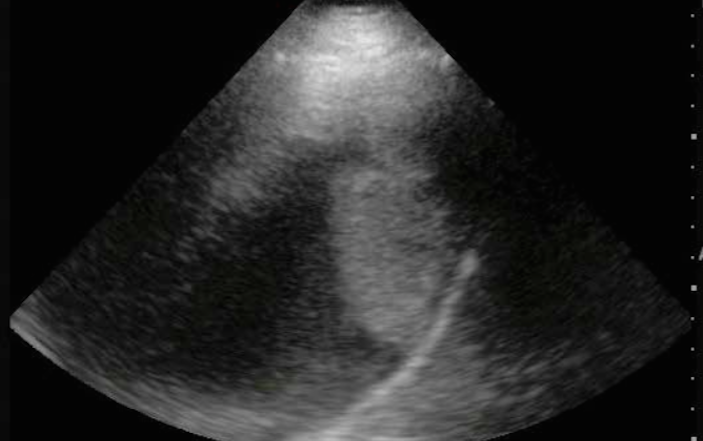

You recommend admission for thoracentesis, feeling he will certainly be stable overnight, but he does not want to stay and requests you drain the fluid and send him home. His family has the same hope so you call his oncologist who also thinks that tapping the fluid and sending him home would be a great idea. After the patient has signed the appropriate consent forms you bring in the portable ED ultrasound machine to help guide your procedure. You maneuver your phased array probe between the ribs to visualize the extent of the pleural fluid and to find the best place to perform your guided thoracentesis. You obtain the following image in the sagital plane taken from the back with the patient sitting upright. What does it show? Are any other images recommended? What should be your next step?

The same sagittal plane image on the prior page is now shown with labels. You don’t really need additional images, but the image at the top of the page needs to have the gain turned up a bit so that you can better make out the lung tissue and what appears to be a mass near where your needle will be entering. With your probe in the long-axis along the patient’s back, you are clearly able to identify the liver on the right anterior part of the screen. This is a key finding as it orients you to the other structures. Note that since you have the probe on the patient’s back, the usual anterior/posterior orientation is reversed from images taken with the probe on the patient’s front. The diaphragm, the pleural fluid, and the floating lung parenchyma are also readily identified.

This image has the gain set higher and shows the floating lung tissue to the left (superior), the anechoic (black) fluid in the center and the hypoechoic (white) line of the diaphragm a little to the right of center. The liver is to the right of the diaphragm. The mass is noted adherent to the diaphragm. This is likely the tumor and would be hypervascular so stay away from it with your needle which will be entering from the area at the top of the screen!

An image from a patient with a hemothorax from one of our prior cases is shown to the right for comparison. The blood is shown by the vertical arrow, but remember that is not where your needle (or chest tube) will be coming from.

An image from a patient with a hemothorax from one of our prior cases is shown to the right for comparison. The blood is shown by the vertical arrow, but remember that is not where your needle (or chest tube) will be coming from.

You prep and drape the patient and your ultrasound probe in a sterile fashion, and proceed to perform a successful thoracentesis under direct ultrasound guidance, making sure to stay away from the tumor. After the procedure your patient feels much better and requests to go home. He does well until the next day when he returns for worsening shortness of breath. Your colleague orders a d-dimer, which is of course positive, and leads to a CT angiogram, which demonstrates bilateral pleural effusion but also two other acute processes. The patient has bilateral large pulmonary emboli and a large pericardial effusion with suggestions of tamponade. He is admitted to the ICU where he has a pericardiocentesis, bilateral thoracenteses and is started on heparin. Unfortunately Occam’s razor did not lead to all of the diagnoses the first time. Sometimes there are multiple disease processes causing a patient’s symptoms.

Pearls & Pitfalls for Ultrasound Guided Thoracentesis

- Position the Patient: Place the patient in a position of comfort for them and you. The ideal position is usually seated upright with legs over the edge of the bed and leaning forward onto pillows on top of a Mayo stand or rolling table. Remember that fluid moves with patient repositioning, and unless loculated will usually flow to the most dependent area of the body cavity in question.

- Choose your Probe: Often the linear array transducer can be used to visualize superficial collections of pleural fluid in thin patients. However in most cases the low frequency phase array or curvilinear probe will be better, especially if the patient has increased muscle mass or thick subcutaneous tissue. The low frequency probe also provides better visualization of deeper structures.

- Identify your Target: Clearly identify the lung parenchyma, the pleural fluid, the diaphragm, and adjacent organs such as the liver or spleen. Position your probe between the ribs to get the best view and alternatively move up and down adjacent rib spaces to find the best interspace to use. Remember that the lungs and adjacent organs will have a mixed echogenic appearance on ultrasound, whereas the pleural fluid will appear anechoic (black), and the diaphragm will appear hyperechoic (white). Map out the superior and inferior borders of the fluid collection and determine the best place to perform the thoracentesis, taking into account anatomic variations during the respiratory cycle. Observe the pleural space through a full respiratory cycle to monitor changes and characteristics of the fluid with diaphragm movement. Use the sonographic images to help localize the ideal interspace for chest tube insertion.

- Proceed: Once all of the thoracic structures have been localized, the thoracentesis can be attempted in a static or dynamic fashion. If the procedure is performed in a dynamic manner, remember to use sterile ultrasound gel and prep the ultrasound probe in a sterile fashion. Direct visualization of the needle will only be noted when the ultrasound beam is angled directly at the needle. Ultrasound “mapping” of the best location followed by a static puncture is usually less cumbersome and equally safe.

- Practice, Practice, Practice: The best way to minimize errors is through experience, so scan lots of normal anatomy. The more scans you do, the better you will be able to differentiate abnormal from normal, even when you may not be sure exactly what the abnormality is.