How to gaze properly to detect painless vision loss complaints.

You’re sitting at the physician workstation in the ED, contemplating another cup of coffee, when a new patient passes you on the way to his room. He appears to be walking slowly and holding on to his wife. You sign up to see him and quickly review his chart: he is 75-years-old, rarely comes to the emergency department and has a past medical history of diabetes, hypertension, stroke and cataracts.

“Good morning, sir, I’m Dr. Kennedy. How can I help you today?” He looks back at you and replies, “Well doc, my wife made me come in to see you. I can’t see out of my right eye.” You ask how long this has been going on and he says, “I’ve had floaters that look kind of like cobwebs for a while. And then about a month ago I started seeing some flashes of light. My vision has been bad and I haven’t been able to see normally for a few weeks, but I thought it would just go back to normal on its own. I guess my cataracts are back.” His wife chimes in and says, “He’s not been able to see well for over a month – he doesn’t see me walking up to him in the house and bumps into things. It’s just continued to get worse.”

The patient goes on to say that he has not had any difficulty with blurred or double vision and denies trauma to the eye or head, eye drainage or itching, eye pain and headache. You ask about surgery and he tells you he had bilateral cataracts removed eight years ago.

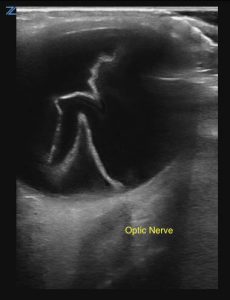

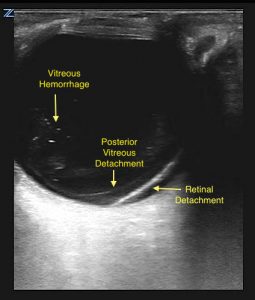

On exam, your patient appears comfortable and has normal vital signs. Heart sounds are regular, no carotid bruits are heard, and the patient is neurologically intact. You do not see any signs of trauma. When you examine his eye, you find no conjunctival injection or drainage, extraocular movements are intact, the left pupil is round and reactive, but he has a right relative afferent pupillary defect. Visual acuity in the left eye is 20/30 with his glasses and only faint movement and light perception on the right. As your panoptic ophthalmoscope is broken, you decide to pull the ultrasound machine into the room and see the following:

While your differential diagnosis list includes central retinal artery or vein occlusion, amaurosis fugax, stroke, posterior vitreous detachment, vitreous hemorrhage and optic neuritis, you feel comfortable in your ultrasound skills and consult the ophthalmology team for your newly diagnosed retinal detachment (RD). As the patient has minimal vision and the retina appears to be entirely detached, you are confident that the patient has a macula-off RD, but would like their input. The ophthalmologist on call says, “Sure, I’d be happy to see him today. Whenever you discharge him, send him down the hall to the eye clinic and we’ll fit him in!”

You update the patient and his wife and tell them you are concerned about a retinal detachment. You hope the ophthalmologist is able to save some of the man’s vision and discharge them to the eye clinic.

Teaching Pearls:

- How to do it:

The fluid in the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye makes it an ideal acoustic window to visualize anatomy with ultrasound. Use your high-frequency linear probe to visualize structures. Based on patient preference, you can either have the patient close their eye and put sterile gel directly onto the eyelid or you can place a transparent adhesive dressing over their closed eye and use ultrasound gel. If you use a transparent adhesive dressing, you want to ensure there are no air bubbles trapped – these will obscure your image. You want to have a “cloud of gel” so that the probe is floating – never put pressure on the globe.

You can brace yourself by resting your pinky finger on the cheek or bridge of the nose to prevent sliding or applying pressure to the eye. Initially, you will want normal gain settings to look at the retina, optic nerve sheath and vitreous in both transverse and longitudinal planes. Make sure there is enough depth to visualize the optic nerve sheath posterior to the globe. Once you have done this, turn your gain settings up significantly to look at the vitreous body; this will highlight subtle findings, such as vitreous detachment or vitreous hemorrhage. Always make sure to get a dynamic view of the eye in both planes – have the patient look left/right and up/down while your probe remains static over the center of the eye to look for abnormalities and movement.

- Normal anatomy:

The eye consists of the anterior and posterior chambers, separated by the lens. The fluid in the eye appears hypoechoic (dark), so it is relatively easy to see the iris, lens, hemorrhage or detachments. The retina is attached at the ora serrata anteriorly and runs behind the vitreous body to attach at the optic nerve posteriorly. The optic nerve should appear hypoechoic, posterior to the globe. The optic nerve sheath diameter can be measured 3mm posterior to the retina, normal being less than approximately 5mm, see blue measurement in image 2.

- Retinal Detachment (RD) vs. Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD):

The retina is contiguous with the optic nerve; if a retinal detachment is present, it should be tethered down at the nerve. When you get a dynamic view and the patient looks left/right and up/down, a retinal detachment should stay attached to and travel with the optic nerve. It appears as a thick, hyperechoic (bright) membrane at normal gain settings and the detached portion can float with eye movement. Literature shows point-of-care ultrasound is both sensitive and specific in diagnosing RDs and emergency physicians have good accuracy.

The vitreous body sits on top of the retina and is not tethered to the posterior eye. If it separates, you will see the PVD hovering above the optic nerve; it looks thin and web-like. Many times you cannot see a vitreous detachment until the eye is over-gained and the image is very bright. Visualizing the detachment in relation to the optic nerve is key in distinguishing RD from PVD.

- Vitreous Hemorrhage:

Frequently, you will see hemorrhage associated with a retinal or vitreous detachment, but it can occur spontaneously. Patients may complain of new floaters, a red hue, or painless vision loss. Since the blood can settle onto the macula while lying flat, symptoms might be worse in the morning. On ultrasound, it appears as echogenic material in the posterior segment and has a swirling appearance on the dynamic view like a washing machine. As this can also be difficult to see at normal settings, look for this after you have increased your gain.

- Both Sides:

Always look at both eyes. The opposite eye can serve as a “normal” for your exam. If you have the same findings in both eyes with unilateral symptoms, those findings are less likely to be the cause of your patient’s symptoms. For example, many people have vitreous hemorrhage and are asymptomatic; if it is present bilaterally, it is unlikely to be the cause of the acute visual change that brings them into the ED.

- Practice!

As with all areas of ultrasound, more practice means better skill and increased confidence. Try putting an ultrasound probe on the eye for your next patient with a visual complaint!

References:

- Gottlieb M, Holladay D, Peksa GD. Point-of-Care Ultarsound for the Diagnosis of Retinal Detachment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1111/acem.13682

- Yoonessi R, Hussain A, Jang TB. Bedside ocular ultrasound for the detection of retinal detachment in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(9):913-917.

- Blaivas M. Bedside emergency department ultrasonography in the evaluation of ocular pathology. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:947-950.

- Shinar Z, Chan L, Orlinsky M. Use of ocular ultrasound for the evaluation of retinal detachment. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(1):53-57.

- Blaivas M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski PR. A study of bedside ocular ultrasonography in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(8):791-799.

- Vrablik ME, Snead GR, Minnigan HJ, Kirschner JM, Emmett TW, Seupaul RA. The diagnostic accuracy of bedside ocular ultrasonography for the diagnosis of retinal detachment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(2):199-203.

- Lahham S, Shniter I, Thompson M, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Retinal Detachment, Vitreous Hemorrhage, and Vitreous Detachment in the Emergency Department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192162.

1 Comment

Good and accurate story for this type of situation.

As an Ophthalmologist I enjoyed reading it.

also I am overly impressed by our local Emergency Room Physicians who are able to perform ultra sound where years ago they were not able to.