-Shay Bintliff, a 73-year-old EP and medical director at a 24-hour urgent care center in rural Hawaii

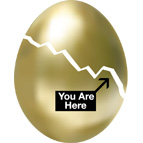

As nest eggs crack, aging emergency physicians face difficult career decisions

As nest eggs crack, aging emergency physicians face difficult career decisionsMany physicians are delaying early retirement, diversifying their incomes, and seeking answers about how the $700 billion federal bailout will affect not only their finances and work lives in the years ahead but also the already strained U.S. healthcare system. When will the economy and stocks recover? Is the worst over? Will EPs see more patients who will lose their health insurance? Do emergency departments have the resources? How will reimbursements be affected?

An October 2007 survey of 1,200 physicians by Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a national physician search and consulting firm, found that in the next one to three years, 48% of physicians ages 50 to 65 said they were planning to retire, seek non-clinical jobs, work part-time, close their practices to new patients, and/or significantly reduce their patient load. But in the year since the survey was conducted, Americans’ retirement funds lost as much as $2 trillion—about 20% of their value.

“It has not been entertaining watching all of my hard-earned money disappear,” says Jeffrey Sankoff, 41, a full-time emergency physician in Denver who has substantial stock investments. “But I’ve got about 10 to 15 years before I need to worry because my 401(k) will just sit there and eventually recover and grow. Those physicians closer to retirement age—hopefully their portfolio is balanced in such a way that this catastrophe won’t have as big of an impact as it’s had on me.”

Christopher Jarvis, a financial consultant and retirement planning expert with O’Dell Jarvis Mandel in Cincinnati, Ohio says most senior physicians fall into one of two retirement categories: “Either they have a lot of money and have done so much planning that this [crisis]doesn’t matter much, or they’re still trying to get to some magical number to support their long-term retirement goals,” he says. “Folks who are still looking for that number have been set back quite a ways by this.”

Greg Henry, 62, an emergency physician at a community hospital in Michigan and former ACEP president, is in the first category. He has strategically diversified his assets over the years, moving them to bonds. “A lot of doctors are not good business people,” says Henry, who is also a clinical professor of emergency medicine at the University of Michigan. “But a lot also got spanked by investing in perfectly good companies.”

Emergency physicians seeking early retirement and a more stress-free life outside the ED are facing tough choices. Ronald Hellstern, MD, a practice management consultant with Dallas-based PSR-MedicalEdge Healthcare Group, says many physicians are realizing they can’t afford to retire on what they have if much of their nest egg is tied to the securities market. “Historically, that was conventional wisdom—the market’s growth rate beat almost everything else,” he says of the trend toward investing in growth-stocks. “When you got closer to retirement, you shifted from those to current-earnings type stocks.” But because most doctors don’t make that shift until they actually retire, this year’s economic turmoil is devastating.

Sankoff, who attended medical school in Canada and has no education debt unlike his U.S.-trained peers, says EPs need better financial guidance. “Most of us finish our medical education without any inkling of what to do with our money,” he says. “I would love to see ACEP take an active role in offering some financial planning seminars, and the annual assembly is the perfect opportunity.”

Eroding incomes and profit margins coupled with a hostile reimbursement environment and the high cost of running a practice have further compromised physicians’ ability to save or invest sizable sums for the future. “In the past, doctors were able to put away exorbitant amounts of money to retire with,” explains Jarvis. “Most simply can’t afford to do that anymore.”

EPs find themselves in an even more vulnerable situation because emergency medicine practices by and large are relatively small, loosely structured entities compared with other office-based and networked medical specialties. Physicians in the group are unlikely to be stakeholders in income-producing investments such as office buildings or surgery centers. As a result, they often don’t hold a lot of equity in the kind of group or profit-making ventures that can provide additional income for physicians who sell their business stake when they retire. Without this opportunity, structuring a secure ‘exit strategy’ for retirement becomes even more essential.

Mark DeBard, 57, an EP working full-time in an inner-city emergency department in Columbus, Ohio, saw his retirement portfolio plummet 25% despite good financial guidance. “This is going to drastically change my retirement plans,” he says. As the oldest EP in his practice group, DeBard is downsizing his house and says he now expects to have to work full-time until age 65 instead of cutting back to part-time work next year as he planned.

Henry says the economic crisis should compel mid-career EPs to evaluate how to better manage their work responsibilities and mature their careers as they age. One upside of emergency medicine is that it offers physicians an opportunity to diversify their incomes through different sideline businesses. “You can work on the urgent care side, industrial medicine or for insurance companies,” he says. “Maybe instead of working 10-12 hour shifts, you need to work six, which is what my body at this point in time can stand.”

“It seems impossible to work more hours each week,” adds DeBard of rigorous front-line ED work. “This is a tough job, and at my age it’s also not easy to tolerate odd hours and evening shifts.”

Richard Stennes, 64, also a former ACEP president, retired from full-time work in 2000 but sees patients at least 5 days a month when he visits his hometown ED in Minnesota. He also makes house calls in the wintertime and practices travel medicine on cruise ships and tours. “It’s very easy to get into concierge medicine,” he says, adding that retiring physicians should maintain their licenses and certifications to keep the option of returning to practice if necessary.

Physicians aged 50 and over – who now comprise nearly half of the U.S. physician workforce – face a veritable “perfect storm” in health care which conspires against their pending retirement. If the tumbling economy doesn’t knock them down, it could be the tide of aging baby boomers, increasingly overburdened emergency departments or the growing ranks of uninsured patients.

“The number one issue for physicians who continue to practice as we grow older is ‘Are my patients safe in my care?’” says Shay Bintliff, a 73-year-old EP and medical director at a 24-hour urgent care center in rural Hawaii. “I don’t care how healthy you are in your old age, you’re not as quick as you used to be and that is something we have to accept. I want to retire the day before I am no longer safe to work in the ED, and that time comes for all of us.”

Bintliff, who plans to retire from full-time ED work next year, says it’s likely more EPs will experience inevitable burn out from having to delay retirement and work longer, especially during a time when more patients need greater amounts of care.

ACEP president Linda Lawrence, MD, says that to survive the national economic crisis, private groups will close their doors to the young and under-insured. “Those populations will then not have access to primary care and frequent the ED in greater rates – EDs will become more important than ever in these lean times.”

With more uninsured patients, more uncompensated care and dwindling reimbursement—including pending Medicare cuts in 2010—the economic downturn will have “the greatest negative impact on emergency medicine” over any other specialty, Lawrence says. The crisis presents a real opportunity for EPs to “turn up the volume on the immediate need to shore up our EDs,” she says. One immediate policy issue is EMTALA reform for the nation’s EDs that provide most charity care.

Brian Hancock, 58, a former ACEP president who is now a physician executive with a national management company, says the government should also lift its cap on the number of residency positions and approve more slots.

“We do not have enough fully trained and qualified emergency physicians to do the job we need across the country,” he says. “Patients are crying out for help. We’ve got to have these conversations as a nation. So maybe the stock market disaster is the straw that breaks the camel’s back and causes this country to realize we can’t afford to do everything and [we]have to get control of the system.”

3 Comments

I am constantly reminded about how poor physicians are at savings. We are viewed by financial planners as having to live up to a certain standard. Does anyone know of any actual data that shows this?

This excellent article illustrates the importance of proactively managing your career as you get older.

Even retired physicians could still continue to enjoy working if they want to since there are a lot of non-clinical jobs available to medical practitioners today. http://www.freelancemd.com