Left untreated condition can lead to 30% to 50% mortality rate.

Case:

A 52-year-old female with a history of peptic ulcer disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of lower chest pain and upper abdominal pain. The patient and family were eating dinner at a local restaurant when she developed symptoms. The patient noted multiple episodes of vomit, followed by dry-heaving on arrival to the ED, approximately six hours later. Her abdominal pain was described as achy to sharp in nature. She denied any shortness of breath, recent travel, fever, similar symptoms in family members or herself, or any other symptoms. Vitals on arrival to the ED: afebrile at 97.4 °F, blood pressure of 148/95 mmHg, heart rate of 78 beats/min, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, weight of 59 kg, and pulse ox of 100% on room air. She appeared well-developed and looked her stated age. She was in mild distress secondary to the abdominal pain. Her cardiopulmonary exam was unremarkable. Her abdomen was soft, with tenderness to palpation within the epigastric region and left upper quadrant, moderate distention, without any percussion, rigidity, surgeries/scars, rebound or guarding.

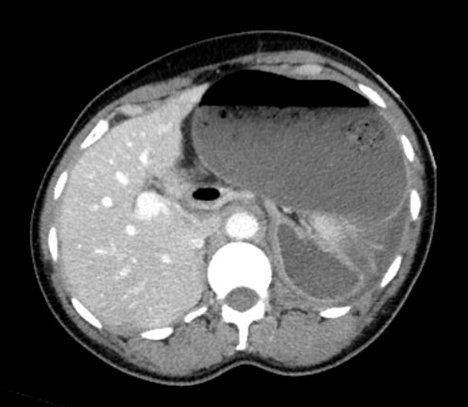

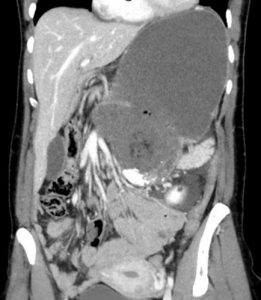

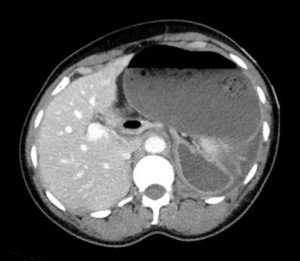

Her EKG was unremarkable for acute ischemic changes. Laboratory evaluation revealed a neutrophil predominant leukocytosis of 15.6, hemoglobin of 13.6, and a platelet level of 286. Complete metabolic panel was only remarkable for a potassium of 3.1. Her lipase was mildly elevated at 78 (7-60 U/L) and lactic acid was 1.9 (0.5-2.2). All other remaining laboratory evaluation including troponins were within normal limits. An acute abdominal series, (as noted in image 1), revealed a large gastric air-fluid level within an otherwise non-obstructive bowel gas pattern. A subsequent CT abdomen/pelvis with intravenous contrast, (images 2 and 3), revealed a significantly distended stomach. In addition, there is an abnormal orientation of the stomach with the pylorus seen posteriorly and a close approximation of the pylorus to the gastroesophageal junction concerning for a possible gastric volvulus.

Clinical Course:

A nasogastric tube was placed with an immediate return of 450 mL of gastric contents. The patient underwent an EGD to evaluate for any gastric ischemia. On EGD, the scope was unable to be passed to the antrum and the stomach appeared to be truly torsed. There were several areas of edema on the mucosa in the mid stomach, but no ischemic changes were noted. The patient was then taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy, reduction of gastric volvulus and percutaneous placement of a gastrostomy tube. Overall, her hospital course was unremarkable. By day 3, the patient was tolerating a clear liquid diet, passing flatus, and noted resolution of the previous abdominal pain. By day 4, she was tolerating a soft diet, having regular bowel movements and was discharged home. At her one-week surgical follow-up she reported she is doing well with plan for PEG tube removal in two months

Discussion:

A gastric volvulus is a life-threatening and emergent condition that requires a quick diagnosis and treatment. The mortality rate ranges from 30% to 50% if left unrecognized, making a rapid diagnosis by the emergency physician of paramount importance.[1]

Gastric volvulus can present in an acute form as a complete obstruction without any prior symptoms, or may be intermittent and chronic with only a partial obstruction sometimes making it easy to miss.

A gastric volvulus involves an abnormal rotation of the stomach around its short or long axis. A rotation to more than 180 degrees can result in strangulation or perforation, making it truly a surgical emergency.[1,2] In a primary gastric volvulus, there is the absence of abnormal intra-abdominal pathology and diaphragmatic defects.[3] This kind of volvulus occurs as a result of a neoplasm, adhesions or abnormalities of the ligamentous attachments of the stomach. A secondary gastric volvulus occurs as a result of abnormalities of gastric anatomy, motility or abnormalities of the diaphragm or spleen.[1] Most cases of gastric volvulus have a secondary cause such as a para-esophageal hernia, peptic ulcers, bariatric surgery, abdominal adhesions and traumatic diaphragmatic injury.[2]

A PubMed literature review was performed involving all cases of a gastric volvulus reported from 1999 to 2018 (total of 43 case-reports). Of those cases, 67% were due to a secondary cause, 91% of them were treated with surgery and death was recorded in three patients.[2]

Patients with an acute gastric volvulus often present with upper abdominal pain and lower chest pain with associated retching. Retching can lead to mucosal tears. Patients often do not exhibit unstable vital signs or appear significantly distressed during the initial disease process. As the disease process progresses, mucosal ischemia can result in mucosal sloughing leading to hematemesis, with eventual perforation, hemorrhage and shock.[1] Since gastric volvulus is a relatively rare occurrence, the diagnosis is frequently made on imaging.

Chest radiography often reveals a retrocardiac and air-filled gastric shadow, while abdominal radiographs reveal a distended fluid-filled stomach.[1] Treatment begins with placement of a nasogastric tube to allow for gastric decompression and immediate surgical consultation for reduction of the volvulus via exploratory laparotomy, laparoscopic surgery or endoscopy.[1] Some case reports have demonstrated resolution of a gastric volvulus with a nonsurgical approach, however, a vast majority of cases require operative intervention.

Given the 30-50% mortality rate if left untreated, a gastric volvulus is a rare surgical emergency with a potentially high morbidity and mortality. It is generally not considered among the top potential diagnoses in a patient presenting to the ED with abdominal pain and retching. Keeping this diagnosis in mind may help to avoid the many potential adverse outcomes associated with this uncommon disease.

References:

- Rashid, F, Thangarajah, T, Mulvey, D, Larvin, M, Iftikher, S. “A review article on gastric volvulus: A challenge to diagnosis and management.” International Journal of Surgery. Volume 8, Issue 1, 2010, Pages 18-24.

- Akhtar, A, Siddiqui, F, Sheikh, A.A, Sheikh, A.B, Perisetti, A. “Gastric Volvulus: A Rare Entity Case Report and Literature Review.” Cureus Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018 Mar; 10(3): e2312.

- Chau, B, Dufel, S. “Gastric Volvulus.” Emergency Medicine Journal. 2007 Jun; 24(6): 446-447.

- Hasan, M, Rahman, S.M, Shihab, H. “A case report on gastric volvulus of a 17 year-old boy from Bangladesh. International Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 2017; 40: 32-35. September 7, 2017.

2 Comments

My father was just diagnosed with a gastric volvulus and had an emergency procedure to untwist the stomach. The underlying cause was a hiatal hernia making space for the stomach to move around. He has been told he must remain on puréed food moving forward. He chews his food extremely well and I am trying to find out why this course of action has been recommended.

He is 84 and has a low to medium level of dementia.

Thank you

I too have a twisted stone plus a hiatal hernia n was told I too need to be operated on n I see the doctor in a month n a half to discuss this problem n it’s coarse!