The true toll of bacterial meningitis.

Bacterial meningitis is an infection that results in inflammation of the meninges, subarachnoid space, and vasculature of the brain. It is a severe and truly devasting infection that requires a high index of clinical suspicion, especially in the neonatal population.

The most common causes within the neonatal population are group B streptococcus (GBS), Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes. While mortality has decreased over the years, morbidity remains high. Clinical signs can be subtle, and symptoms may be non-specific, with a lumbar puncture (LP) sometimes being deferred in unstable neonates.

A prompt diagnosis and early administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics are key in decreasing morbidity and mortality. We presented the case of a 12-day-old African-American neonate born at 37-weeks and three days without prenatal care, who was subsequently diagnosed with GBS meningitis.

Our patient’s next three days in the PICU were complicated by status epilepticus requiring three anti-epileptics (phenobarbital, fosphenytoin and levetiracetam) and multiple apneic episodes requiring stimulation. The GBS isolate was found to be highly penicillin-susceptible for which antibiotics were further de-escalated to ampicillin. A repeat LP was attempted but was unsuccessful.

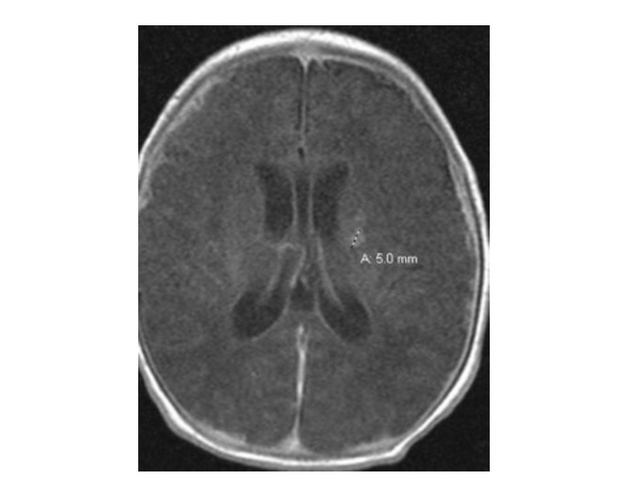

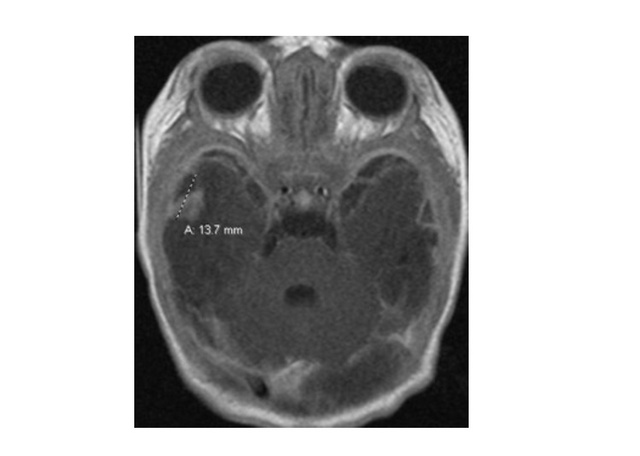

A head ultrasound on day-8 showed slight ventriculomegaly for which pediatric neurosurgery was consulted. In addition, there was evidence for vascular insults to the left thalamus and left basal ganglia. A subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed on day-12 was concerning for post-infectious cerebritis with ischemic changes within the left basal ganglia measuring up to 5 mm, (Fig. 2),

and right temporal lobe at 13.7 mm, (Fig. 3), with multiple small areas of hemorrhage throughout bilateral middle cranial fossa, posterior fossa, right occipital region, and left basal ganglia.

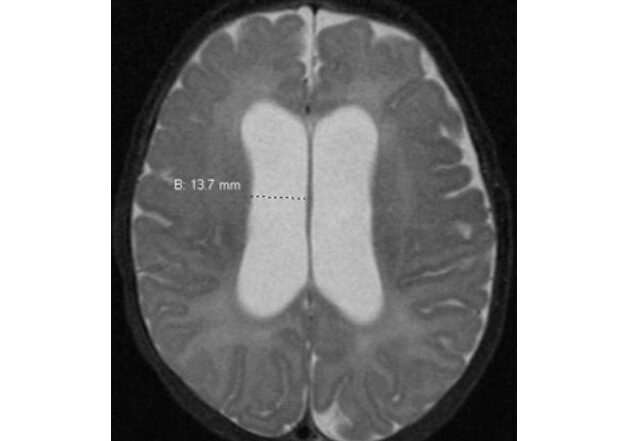

Given these findings, her antibiotic regimen was increased to four weeks of parenteral therapy. By day-18, an audiology evaluation was consistent with hearing loss bilaterally. A repeat MRI performed showed mild residual leptomeningeal enhancement/dural thickening, resolution of previously seen abnormal enhancing foci, interval encephalomalacia within the right temporal lobe, and an increased size of the ventricles up to 13.7 mm, (Fig. 4).

The patient was discharged home on day-30, after the completion of a four-week course of antibiotics. At 12 months post discharge, the patient continues to follow closely with physical therapy. Her ventriculomegaly has stabilized and her development and social interactions have greatly increased with the addition of hearing aids. At the present time the patient is scheduled to have a right cochlear implant placed.

The complications arising from neonatal meningitis can be vast. Within the acute setting they include: increased intracranial pressure, cerebral edema, ventriculitis, cerebritis, brain abscess, hydrocephalus (most common in patients with GBS and seen in about 25% of patients overall), cerebral infarction, arterial stroke, cerebral venous thrombosis, subdural empyema, and subdural effusion.[2]

Within the chronic setting they include: encephalomalacia, developmental delay, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and cortical blindness.

As we have shown in this two-part case report, bacterial meningitis is truly a devastating infection that requires high index of clinical suspicion, especially in the neonatal population. Clinical signs can be subtle, symptoms may be non-specific, but the clinician needs to maintain a high index of suspicion. As bacterial meningitis is most common within a neonate’s first month of life, a prompt diagnosis and early administration of intravenous antibiotics are crucial in decreasing morbidity and mortality.

References:

- Edwards, M, Baker, C. “Bacterial meningitis in the neonate: Clinical features and diagnosis.” May 9, 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bacterial-meningitis-in-the-neonate-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

- Edwards, M, Baker, C. “Bacterial meningitis in the neonate: Neurologic complications.” February 28, 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bacterial-meningitis-in-the-neonate-neurologic-complications

- Lawrence, C, Boggess, K, Cohen-Wolkowiez, M. “Bacterial meningitis in the infant.” Journal of Clinical Perinatology.” 2015 Mar; 42(1): 29-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4332563/

- Kaplan, S. “Bacterial meningitis in children older than one month: Clinical features and diagnosis.” April 17, 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/bacterial-meningitis-in-children-older-than-one-month-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

- Vukovic, A, Sobolewski, B, “The Febrile Infant—University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine Collaboration.” http://pemcincinnati.com/blog/the-febrile-infant-taming-the-sru-collaboration

- Zarkesh, M, Hashemian, H, Momtazbakhsh, M, Rostami, T. “Assessment of Febrile Neonates According to Low Risk Criteria for Serious Bacterial Infection.” Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 2011 Dec; 21(4): 436-440.

- Kanegaye, J, Soliemanzadeh, P, Bradley, J. “Lumbar puncture in pediatric bacterial meningitis: defining the time interval for recovery of cerebrospinal fluid pathogens after parenteral antibiotic pretreatment.” Pediatrics. 2001 Nov;108(5):1169-74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Lumbar+puncture+in+pediatric+bacterial+meningitis%3A+defining+the+time+interval+for+recovery+of+cerebrospinal+fluid+pathogens+after+parenteral+antibiotic+pretreatment&TransSchema=title&cmd=detailssearch

- Tesini, B. “Neonatal Bacterial Meningitis.” July 2018. Merck Manual. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/infections-in-neonates/neonatal-bacterial-meningitis

- Levine, B. “EMRA Antibiotic Guide.” 18th Emergency Medicine Resident Association Antibiotic Guide.

- Muller-Pebody B, Johnson, A, Heath, P, Gilbert, R, Henderson, K, Sharland, M. Empirical treatment of neonatal sepsis: are the current guidelines adequate? Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2011;96(1):F4–F8.