Knowing the finer points of EMTALA – and keeping your staff up to date – will help your department stay compliant while promoting top quality care.

Dear Director: A patient complained to our CEO that their EMTALA rights were violated when we transferred them. Now I have to prove to our administration that everyone knows what EMTALA is and is compliant with it. Is there anything I could have done to prevent this situation, or is it just inevitable?

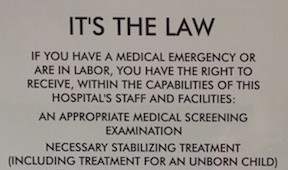

Congress enacted the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in 1986. As we know, this meant the public would have access to emergency services regardless of their ability to pay, insurance status, national origin, race, creed or color. EMTALA applies to all Medicare-participating hospitals that offer emergency services and requires that hospitals provide a medical screening examination (MSE) when a request is made for examination. Hospitals must also provide treatment for any emergency medical condition (EMC) that is uncovered, including active labor. Hospitals must stabilize EMCs within their capability and transfer appropriate patients for further stabilization if necessary. EMTALA was passed as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 – otherwise known as COBRA. Many laws were part of COBRA, including the statute that allows for continuation of medical insurance benefits after termination of employment.

While EMTALA started as an “anti-dumping” law, designed to prevent private hospitals from transferring uninsured or underinsured patients to public hospitals, enforcement and fines seem to come in waves. In 2000, Congress made EMTALA enforcement a priority with nearly as much in penalties in that year as in the previous 10 years. EMTALA made national headlines again in 2013 when a Nevada psychiatric hospital was accused of sending patients to California by bus without making arrangements for their care. According to the Office of the Inspector General’s website, about 8-12 EMTALA-related cases are settled against hospitals each year [1].

By now, you would think that every ER doc should know the ins and outs of EMTALA. The law has been around for 30 years. EMTALA is frequently discussed in residency training and EMTALA-related questions often pop up on list-servs. Nevertheless, there continue to be differences in how individual emergency physicians interpret and apply aspects of the law. As a medical director, you’re charged with maintaining consistency of this performance, mitigating risk to your patients and hospital, and developing a culture of EMTALA understanding and awareness. Some groups are proactive and require all of their physicians to undergo an annual EMTALA CME course. On the other end of the spectrum, some ER groups have no written policy about EMTALA and leave it to the medical director to educate their staff.

In talking to colleagues, it appears that most EMTALA-related complaints are from patients who stated that they didn’t receive a medical screening exam or who didn’t want to be transferred. While patients may not use the term “EMTALA” in their complaints, this law remains a high risk area for us. Violations can result in fines and even exclusion from the Medicare program (which could be fatal to an emergency physician’s career). In a previous ED I worked in, the hospital network had one of their attorneys perform a “risk assessment” of our ED. I was proud of the work we were doing and thought that we had robust quality assurance and quality improvement programs. We had numerous ongoing projects that led to positive changes for the patients and the ED. However, we had one glaring fault in the reviewers mind—we weren’t doing anything to evaluate our EMTALA process.

EMTALA Coverage

Medical Screening Exams

Under EMTALA, everyone who comes to the ED and requests medical care has a right to a medical screening exam. This screening examination should be reasonably calculated to uncover any emergency medical condition. The screening examination must also be non-discriminatory, meaning that all patients with similar complaints must receive similar screening exams and/or testing. As previously mentioned, the requirement to provide a screening exam exists regardless of insurance or ability to pay. This screening exam requirement also includes specialty care, and includes access to specialists who are on-call. Therefore if your ophthalmologists are on-call and they have privileges that extend to treatment of a ruptured globe, or your on-call orthopedist has privileges for femur fracture surgery, they shouldn’t be refusing to care for these patients and requesting that you transfer them.

Transfers

Part of the reason EMTALA was put into place was to prevent patient dumping – transferring patients due to lack of insurance. We need to care for the patients that we’re able to care for given the limitations of the hospital. At my site, we transfer about 1% of our patients a month with the primary reasons including: psychiatric bed availability, PICU care, pediatric surgery, and major trauma and burns. In each case, after the patient is stabilized within our capabilities, a transfer form is completed that documents the accepting hospital has the capacity (bed availability and expertise) to care for the patient and that there is an accepting physician. The risks and benefits are also discussed and documented with the patient. The law also states that we cannot transfer patients without their consent. The law requires specialty centers, such as trauma or burn units and regional referral centers to accept patients from a transferring hospital if specialized services aren’t available at that hospital. So if you’re a site that accepts patients, you may want to consider a log to document each request, particularly if there are patients you cannot accept based on bed availability and expertise. Additionally, EMTALA covers the mode of transportation, as patients need to be transferred under “qualified personnel and transfer equipment.” This may be quite a departure from how some EDs transfer certain types of patients such as pediatric psychiatric patients whose parents are driving them for in-patient psych hospitalization rather than the patient being transferred by ambulance.

Left Without Being Seen

Because patients are entitled to a MSE, patients who leave without being seen present a specific challenge. Many of these patients don’t notify the nursing staff prior to leaving, but for patients that do tell staff, the triage nurse or a provider should reiterate to the patient that the hospital will provide a MSE if the patient is willing to stay and should document the interaction accordingly. CMS may consider long waits as EMTALA violations. Extended wait times are an evolving topic with respect to MSEs. On the most recent CMS EMTALA Physician Review worksheet, [2] there is a question for the reviewer to comment on evidence of an inappropriately long delay based on the patient’s clinical presentation between ED arrival and MSE. What constitutes an inappropriately long delay is clearly a judgment call for the reviewer, but begins the discussion on relating door-to-doc times to chief complaints and appropriate/acceptable wait times.

Against Medical Advice

Patients need to be made aware that they’re entitled to a complete medical screening exam and the risks and benefits specific to their complaint should be explained to them so that they can make an informed decision prior to leaving AMA. We must determine that the patient has the capacity to refuse the offer of a MSE or stabilizing treatment, document that mental capacity, secure the individual’s written and informed consent to refuse care, and finally, if the patient refuses to sign a form, document that refusal and obtain a signature from a hospital representative that can serve as a witness.

Prevention

When CMS investigates an EMTALA complaint, or when you need to convince your C-suite that your team knows what they’re doing, education and preventive maintenance are your friends. Obviously, CMS will review the specifics of the case in question. However, they’ll also want to review the culture of your facility.

While it seems inherently obvious that patients show up to the ED and we take care of them (provide a MSE), it only takes one time where we didn’t provide a MSE or we transferred someone inappropriately to generate an EMTALA complaint. I’ve had to meet with CMS or state investigators a few times over the years. Regardless of the topic they’re investigating, your job is to show that the medicine provided is of high quality and the department is compliant with hospital policies.

By creating a culture of understanding and compliance with EMTALA and by being able to show your efforts through documented activities, you should have no trouble convincing your executive team or CMS investigators of what you (hopefully) knew all along—that your team is aware and compliant of the complexities of EMTALA.

Show or Tell

When it comes to proving EMTALA compliance, it’s not enough to know the law. You may have to prove compliance through the culture of your facility. Here’s how:

- EMTALA should be discussed on a regular basis at your department meetings. You’ll use your department minutes to prove this. Because of the implications about stabilization involving specialists, it’s probably worth doing an EMTALA update at one of your hospital’s medical staff meetings every year.

- Because the highest risk of an EMTALA violation occurs with a failure to do a medical screening exam or an issue with transferring a patient, quality assurance efforts should be focused there.

- Make sure everyone in your department knows who and who cannot perform an MSE (docs, MLPs, nurses) and what is included in your hospital policy about the MSE. It’s probably worth doing a small chart audit 2-4 times a year where random charts are selected to insure that an MSE is performed as defined by your hospital policy and that the appropriate work up and stabilization takes place and is documented.

- With today’s EMRs, it’s fairly simple to develop a phrase that says the patient has been evaluated and is stable for discharge.

- I find that more effort should be put towards a formalized audit process for your patients who are transferred. This should include documentation of the appropriateness of transfer, discussion of risks and benefits, and the necessary signatures. If you’re not already doing this, you might be surprised by the results. Once you achieve a high level of performance over a period of months, you can decrease your auditing to either a smaller sample size or every second or third month. Break down these results to the individual physician level and be sure to show your data to your providers at your staff meetings.

REFERENCES

1. https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/patient_dumping.asp

2. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/Downloads/R134SOMA.pdf

3 Comments

Good review. One point of clarification, though, is necessary:

When discussing AMA,we need to document *capacity* not competence as you write. Competence is legally adjudicated, capacity is clinically assessed.

Seems semantic, true, but these terms have specific legal definitions that make them non-interchangeable. As the AMA process is high-risk, making the documentation as watertight as possible is essential.

I second ToxDoc: Thank you Dr. Silverman, great EMTALA article. Please be sure to use the language distinction and correct description of decision making capacity, not competence, when discussing medical consent or refusal (ie. AMA).

Respectfully,

Scott

Thank you for pointing that out. You are completely correct. It is capacity as you point out. Thanks again.