Depositions are not casual conversations or informal get-togethers providing you with an opportunity to prove your innocence. They are well-choreographed, deep-sea fishing expeditions designed to find the tools the plaintiff attorney needs in court to hang you on your own words. Be wise. Be careful. There are only two things you can never take back in this world, a bullet and your testimony in a deposition.

THE CASE: A 38-year-old male smoker came to the ED with “indigestion” pain in his epigastrium. He was evaluated by the EP, given a GI cocktail, and discharged without any testing after his pain resolved. The patient came back again with more significant chest pain several days later. An EKG showed inverted T-waves in the precordial leads with no cardiac enzyme changes. However, due to the EKG changes, the patient was admitted for further testing. A stress test was done the following day and showed no reversible ischemia. The patient was discharged home. Later that afternoon, the patient was found dead. Autopsy showed that an MI killed him.

“Don’t worry,” says the cool, confident attorney. “I know this isn’t something you have much experience with. Can I offer you a beverage? Perhaps, some simple yes or no questions would be easier for you to start out with? Your name is Dr. Smith, isn’t it?”

“YYYYes.”

“That wasn’t so hard now was it?”

“No. It wasn’t.”

“Nice day outside, wouldn’t you say?”

“Yes.”

“Well Dr. Smith, would you also say that misdiagnosing Ms. X’s PE resulted in her death?”

******

Depositions are not casual conversations or informal get-togethers providing you with an opportunity to prove your innocence. They are well-choreographed, deep-sea fishing expeditions designed to find the tools the plaintiff attorney needs in court to hang you on your own words. Be wise. Be careful. There are only two things you can never take back in this world, a bullet and your testimony in a deposition.

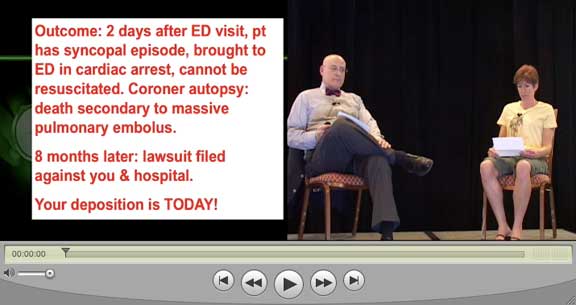

In order to help you in this quest for survival, William Sullivan takes Greg Henry through a mock deposition. EPM editors read between the lines, explaining how simple statements can make a big difference when you’re in the hot seat.

-Kevin Klauer, DO

William Sullivan: Dr. Henry I understand that you are the defense expert in this case, is that correct?

Greg Henry: I have been asked to review this case by the defense I would not use the term that I am a defense expert. I am merely someone who elucidates the truth.

WS: Tell me, what is it that emergency physicians do?

GH: An emergency physician generally confines his work or area of expertise to patients who come to an emergency department or at least some form of outpatient setting and the emergency physician is charged with evaluating the patient for the acute complaints with which he or she presents. The emergency physician is in no way representative of primary care or going after all aspects of the patient’s care but it relates to those things which are brought directly to the department.

{note: Don’t allow the plaintiff’s attorney to expand your professed expertise to thin areas.}

WS: When you say, “brought directly to the department,” you are also referring to other conditions, ancillary conditions that might be causing the patient’s acute complaints, is that correct?

GH: Correct. I mean obviously an emergency physician must properly assess the patient and decide what is reasonable under the circumstances. There is no one standard of care and it always depends on the individual patient. From their presentation the emergency physician then makes reasonable decisions as to how this disease process will be further elucidated.

WS: You mentioned disease process. What if the physician doesn’t know what the disease process is?

GH: Well frequently we don’t. In fact it’s put forward in many of the studies that about 50% of the time when the patient leaves with abdominal pain, for example, we do not have a specific diagnosis. At least 30% of the time when people leave with chest pain we do not have a specific diagnosis. But what we can do is start the patient down a path which will lead to the correct diagnosis. It is not incumbent upon the emergency physician to have the exact diagnosis at any moment. It’s about whether the emergency physician can properly enter the patient into the system where a correct diagnosis or a final diagnosis can be obtained.

{note: Remember that you never want to expand the responsibility of the defendant.}

WS: You mentioned chest pain. You said that in 30% of the patients with chest pain the emergency physician doesn’t come up with the diagnosis. Given that this patient, Mr. Smith, was complaining of chest pain on his second visit, how should an emergency physician manage a patient who presents with a complaint of chest pain?

GH: Well you’ve raised an interesting question, counselor. Chest pain is one of the five most common symptoms that present to the emergency department. I think it is important to note whether a patient is presenting for their first time or is coming in for a repeat visit. Occasionally, when the disease process has not gone the way we predicted, it’s important that a patient return so that we get another chance.

WS: When a patient comes in to the emergency department with chest pain, how should an emergency physician assess and manage that patient?

{note: This question tempts the expert to speak to the best practices and not the minimum standard of care.}

GH: Well there are multiple answers to that depending on the patient involved. First, the emergency physician has to take a reasonable history, the appropriate history. They have to do the appropriate physical, do testing which he thinks will put him in the right direction. And then, from that, and the biggest decision he must then make is, can this patient be evaluated logically on an outpatient basis or is it incumbent upon him to admit the patient for more intensive or aggressive workup.

{note: Instead of expanding the responsibility of the defendant, Dr. Henry simplifies and limits it.}

WS: Talk a little bit about patients who present with epigastric pain. Isn’t it true that someone who presents with epigastric pain could be suffering from angina or a heart attack?

GH: They could be. Obviously the epigastrium is where everything in the body sort of centers. It could be something in the belly, it could be something in the chest. It is not always easy to separate these things out. In fact, there is no known study that says that any one particular medication or any one particular activity can separate out cardiac disease from gastrointestinal disease. So it is always a conundrum. Now there are those patients who will have point tenderness over the gallbladder, for example, which makes this a little bit easier. But the generalized nonspecific epigastric pain is one which requires physician judgment.

{note: The attorney wants to pin the expert down to a specific test that wasn’t done. Dr Henry emphasizes that sound process and good judgement is the standard of care.}

WS: If you have someone who is, say, a male smoker, who is having epigastric pain and hasn’t been to the emergency department before, shouldn’t t

he emergency physician at least consider whether or not that pain might be related to the patient’s heart as opposed to their stomach or gallbladder or other abdominal organ?

GH: I think it’s certainly somewhere on the list. Now there will be factors in the history or in the physical that may push the physician in one direction or another. I will be very candid and say that the initial presentation, in the first visit, the fact that the patient responded to a “G.I. cocktail” in no way rules in or rules out myocardial disease. I will also say this: It’s fortunate that this patient came back in again and had normal markers. What that means is that at the time the patient was in the department the day before he could not possibly have had a myocardial infarction. The enzymes were normal, they should have been up six hours after the infarct. So fortunately, the patient in retrospect was not having infarct of the time he was in the emergency department.

{note: While Dr Henry emphasized what is known, he also notes things that couldn’t be known.}

WS: If one of the things that is possible with a patient who has epigastric pain is cardiac disease, what should a physician do if a patient may be having cardiac problems that are a source of the symptoms?

GH: This is where physician judgment comes in. There is no book that we given in medical training which says on it, The Standard of Care. The standard of care is that which a reasonable physician of like or similar training might do under like or similar circumstances. So it takes a combination of his training, experience, all of his education, to make a reasonable diagnostic and treatment plan for the patient. I will, with your indulgence, say right now that on the initial visit, I would be willing to concede that the current standard of care was not met. But by saying that I do not suggest that that visit caused harm to this patient. To have malpractice you have to have a violation of the standard of care which is proximately related to the harm and in this case, this patient came back having had no signs of an MI, went to the Cath Lab, was seen by a cardiologist, had a negative stress test and then the cardiologist sent the patient home. I think it is beyond the pale to suggest that the emergency physician is the ultimate cause of this patient’s demise.

{note: While Dr Henry is accurately stating the law, he might have been stopped by a more aggressive trial attorney. Be careful not to look too much like an advocate.}

WS: You concede that the standard of care was not met. Why wasn’t it?

GH: I’m willing to admit that the current discussions about the management of chest pain include the possibility of occult angina, of chest pain in the area of the stomach which certainly could be related to the heart. I believe in most institutions at this time a positive provocative test with a G.I. cocktail does not constitute the standard of care in ruling out underlying cardiac disease. Interestingly enough, on his next visit the patient had everything to rule out cardiac disease including markers and a stress test and none of that showed the disease. At some point in time there is a sense of reasonableness here that we need to invoke.

{note: Dr. Henry does a good job of bringing the jury back to common sense.}

WS: When you say that G.I. cocktail doesn’t rule out cardiac disease, what should an EP do to rule out cardiac disease?

GH: Obviously it depends on whether it’s ongoing or pain which has gone away. If the patient in the department has three sets of normal markers separated by between four and six hours – and I’m willing to entertain a debate on the timing of markers – and three normal EKGs, the chances of that patient leaving the emergency department and dropping dead in the next 30 days are less than one in 1000. That’s why it is still perfectly acceptable in most communities for the emergency physician to set the patient up for a stress test of some kind, which is usually determined in conjunction with cardiology, within the next few days. Which is exactly what happened in this case and unfortunately even the stress testing which the cardiologist did is not 100% as evidenced by the fact that this patient still went home and dropped dead from a heart attack.

{note: Dr. Henry is drawing attention back to the true standard of care: what similar physicians in similar circumstances would have done.}

WS: What I wanted to find out from you was this: how does an emergency physician go about ruling out cardiac disease?

GH: The cardiac disease I’m sure you’re referring to here is atherosclerotic ischemic disease, because we’re not talking about valvular heart disease or pericarditis and that sort of thing. The way that it is generally approach is with a series of markers, a series of EKGs and then, if those are positive, then it’s very easy to a direct the patient immediately to cardiology who will make decisions about management such as catheterization. However, if the studies are all negative that still doesn’t mean the patient doesn’t have an underlying coronary artery disease. It is still the largest killer of the country. So the emergency physician then needs to inform the patient that cardiac has not been fully ruled out, and get him scheduled for evaluation by cardiology with some other test depending on what’s currently in vogue at that hospital at that time.

{note: Again, The attorney tries to pin Dr. Henry down to a specific test that wasn’t performed. While speaking knowledgably, he emphasizes judgement over cook book medicine.}

WS: You mentioned that stress tests aren’t 100% sensitive in detecting cardiac disease.

GH: No stress test is 100%. In fact, at best, our stress tests are somewhere in the 85 to 90% range. It is then the decision of cardiology – by putting together all the history and all the factors – as to whether they want to take a patient, even with the normal stress test, to have a catheterization. It is always good to remember that catheterization is not a benign procedure. Patients can bleed. You can actually stimulate cardiac arrhythmias in a catheterization, let alone the die load which leads to kidney problems. So it is a lesser-of-evils decision on the part of the cardiologist whether they want to take a patient with normal enzymes and normal EKGs to the cath lab.

{note: Dr. Henry emphasizes the fact that the EP is not the final word in most care decisions.}

WS: An emergency physician admits a patient to rule out cardiac disease and they know the patient is going to have a stress test done. Even though that stress test is, at best, 90% accurate. Shouldn’t the EP do anything else in terms of ruling out cardiac disease?

GH: I have no idea what that would be because it we’re going to look at – and by the way it’s not cardiac disease, it’s do we have surgically or interventionally correctable cardiac disease – there are people who have quite normal cardiac vessels are drop dead from a heart attack on a coronary artery spasm basis. So the real question is do they have cardiac disease on which we have a reasonable chance of improving them with intervention. And the study of choice is to have some sort of stress test and a decision made by cardiologist as to whether they will have catheterization. The only thing that we can really do at this point in time is with clinically significant stenosis we can help open the stenotic areas with stents, or in severe cases – such as my own, counselor – an open-chest bypass proc

edure.

{note: While it is tempting to get into a personal tit-for-tat with the attorney, jurors can be turned off if you seem argumentative.}

WS: You mentioned before that the stress test is the test of choice in evaluating cardiac disease?

GH: It depends on where you are which type of stress test. There is not one type of stress test. There are multiple forms of stress test and if the physicians are still not satisfied – such as when it’s waxing and waning chest pain – then they make the decision that it’s worth the risk and worth the possible problems to go ahead with a catheterization and, if necessary, the stenting of arteries.

{note: Here Dr. Henry does a good job of demonstrating the complexity of the problem.}

WS: So, the catheterization is actually more sensitive in finding cardiac disease then a stress test would be.

GH: Well, it’s more sensitive in localizing one thing and that is obstruction of the coronary arteries. There are people who have coronary artery disease which is reactive to various chemicals and so they may have relatively clean arteries – it may look quite good – and yet under stress, those people get something called Prinzmetal’s Angina – they get spasm and can die from that.

{note: The Plaintiff’s attorney wants to make things look simple. The expert demonstrates that the decision is complex.}

WS: Does an emergency physician have a duty to admit someone if that patient has angina?

{note: This is a simple question that appeals to the jurors. Hence, Dr Henry gives a simple negative answer, but then qualifies it.}

GH: We have patients with angina all the time who go home. If they’ve been properly worked up and are being treated, they don’t all come in. But a patient who comes in with chest pain, which is new onset as this one, and one believes that this could be cardiac in nature, I believe that unstable angina should be admitted and a decision made. Now, having said that, I understand that we can’t always get someone in immediately for a stress test and so at least the stress test has to be set up for the near future to decide what’s going to happen.

WS: How does one make the decision whether or not to admit the patient or set up a stress test in the near future?

GH: The biggest question is whether the resources are available. Some hospitals have 24-hour functioning chest pain laboratories which can do this around-the-clock. Most of us do not have that and so if the patient is pain free and has normal vital signs, normal vital signs, normal markers and normal EKGs, that patient can be set up as an outpatient. If the patient has ongoing pain then I believe contact with cardiology is required and a decision made about how the chest pain will be handled.

WS: You spoke before about unstable angina and how these patients require admission.

{note: Attorneys often take an answer and reshape the expert’s response. Here, the attorney attempts to make the expert say that angina patients need admission. But Dr. Henry sees the trap and restates his previous answer with elaboration and emphasis.}

GH: I believe that’s true if it’s truly unstable, and I gave you some of the definitions of that. Certainly ongoing, waxing and waning pain is unstable. Certainly pain which is associated with changes in vital signs is unstable. Other changes on physical exam might rate the classification of instability. Now we have lots of patients who function every day with stable angina and they’ve been worked up, decisions have been made that there is no surgical intervention for those folks and they treat themselves with various medications. But they don’t have to be admitted to the hospital.

WS: Why do unstable angina patients have to be admitted to the hospital when other patients don’t?

GH: Well the unstable patients may be crescendoing and may be moving toward an occlusion and acute myocardial infarction. So, that’s why true unstable angina probably needs admission or certainly observation in the emergency department until their pain is gone and their markers are considered normal. But I wouldn’t for a second pretend that the literature is clear on this issue as to who can go home and who should come in. It’s what you’re willing to accept as the acceptable miss rate on a disease. I mentioned earlier that three negative markers and three negative EKGs secession of pain, your chances of dying in the next 30 days are less than one in 1000 patients.

WS: Someone who has unstable angina who has one normal set of cardiac markers, does that tell you anything?

GH: It’s interesting you mentioned that because everybody has been interested in this topic. Emergency doctors would like to clear their beds as soon as they could is long as the patient is safe. There is no published study in English literature which can say that one negative EKG and one negative set of markers is adequate to clear you from having acute coronary syndrome.

WS: And acute coronary syndrome is potentially deadly, isn’t it?

GH: As is anything in regards to the heart. There’s really two organs you need every second of every day, your heart and your brain, and that’s where we tend to concentrate our efforts in emergency medicine.

WS: Ever hear of the saying, “Time is muscle”?

GH: Well that’s an advertising slogan for a company that was giving thrombolytics for coronary disease. I’ve certainly heard the phrase, and that’s why we check to see if there are bumps in the markers. You essentially have not had significant coronary injury if your markers do not bump.

WS: Do you agree with the statement that “Time is muscle”?

GH: Only in its broadest perspective. It certainly does not mean that everybody with chest pain is dying of heart disease. What it means is if you are obstructing a coronary artery, and we have reasonable proof of that either from the EKG or the markers, then rapid resolution and decision-making is important and I agree with that.

WS: In other words in someone who is having an acute myocardial infarction, the longer it takes to open that artery or treat that patient, the more muscle damage that occurs, is that correct?

GH: Well that’s generally the feeling, that the sooner they perform a catheterization and they open up the vessel – assuming that that’s the cause – they will do better. Now again with our patient we know, because of his second visit, he did not have increased enzymes, he had not had a myocardial infarction prior to coming to the emergency department.

Greg Henry has given opinions on over 2000 cases, approximately 88% on behalf of the defense.

Mock Deposition from Logan Plaster on Vimeo.

1 Comment

Outstanding! Truly outstanding! I humbly, respectfully recommend to any and all candidates for U.S.M.L.E. III and for Board Certification and Re-Certification.