Should EPs be liable for initial CT interpretation?

Click here to read the original case

Click here to read Dr. Pregerson’s Analysis: A Migraine With Big Red Flags

Q. Was the patient’s care within the scope of reasonable practice?

Outcome: The case proceeded to trial. In addition to the above arguments, the defense also argued that earlier treatment would have been unlikely to have made a difference in the patient’s outcome. However, the extent of the delay and the multiple alleged errors in care seemed to have inflamed the jury. The parties agreed to a confidential settlement prior to jury deliberations. See graph below for the EPM survey results.

Navigating Between Occam’s Razor and Hickam’s Dictum

Basilar artery strokes are devastating with a mortality rate greater than 70%. Adding to the high morbidity and mortality is the fact that strokes involving the posterior circulation tend to cause atypical symptoms. It is uncommon for ischemic strokes involving the anterior circulation to cause headaches, yet 40% of ischemic strokes involving the posterior circulation cause headaches. Vertigo, nausea, and/or vomiting are uncommon in anterior strokes, but occur in 50-70% of posterior circulation strokes. Posterior strokes are also more likely to cause facial paresis/pain, visual disturbances, and hearing loss. Unfortunately, there is a large overlap between migraine symptoms and posterior stroke symptoms. The International Headache Society is in its third iteration of headache classifications [1]. Under these classifications, migraine headaches by definition must be associated with either nausea and vomiting or with photophobia/phonophobia. Additionally, by definition, migraine headaches with aura include reversible symptoms of focal CNS dysfunction such as vertigo, hearing changes, dysarthria, vision changes, or decreased level of consciousness. Migraine headaches with basilar aura (formerly termed “basilar migraines”) may present with the same symptoms as a basilar stroke.

A review of literature shows that there are literally dozens of clinical findings that might suggest need for further workup of headache. ACEP guidelines [2] recommend neuroimaging in headache patients with abnormal neurologic findings, altered mental status, change in the pattern of previous migraines, headache waking patients from sleep, and headache associated with syncope, nausea or sensory distortion. A Medscape article by Chawla [3] suggested that neuroimaging is indicated for headaches that are first or worst; that are associated with fevers, seizures, or abnormal neurologic exam; that are new and persistent; that have new onset in patients after age 50; that are located posteriorly; or that represent a change in pattern from previous headaches. Detsky et al. [4], suggested neuroimaging when chronic headaches are associated with “high-risk” features such as cluster headache or undefined headache, abnormal findings on neurologic examination, headache with aura, headache aggravated by exertion or Valsalva-like maneuver, and headache with vomiting. In clinical practice, it would be difficult to find a headache that doesn’t meet at least one of these criteria.

This patient presented with pain that was typical of her prior migraine headaches, but she had additional symptoms that were not typical of prior migraine headaches. While new symptoms are not diagnostic of a different process, they can raise the suspicion that another etiology for the headaches may be involved. At this point the clinician is faced with a decision whether the patient’s symptoms represent an uncommon presentation of a common disease or whether the symptoms represent a common presentation of an uncommon disease. In other words, one must choose between Occam’s razor and Hickam’s dictum. On one hand, I agree with the plaintiff’s argument that new onset of syncope, speech changes, hearing changes, and facial numbness were not typical of a migraine headache. On the other hand, I have also treated many migraineurs who present with symptoms different from their typical migraines and who respond quickly to typical migraine treatment. Although medical literature may suggest that the patient’s initial management may not have been optimal, I think it is reasonable to initially treat a patient with prior migraine symptoms and a headache that was typical of those prior migraines as having a migraine with aura rather than rushing the patient to neuroimaging. However, lack of improvement in symptoms after receiving medications for the headache may also suggest a need to reconsider the diagnosis. The fact that this patient’s discharge orders were written and then canceled after the patient was reevaluated suggests that the patient had not been thoroughly reevaluated prior to being discharged. The defense argued that the patient’s symptoms were likely due to hyperventilation. While hyperventilation may result in circumoral numbness, it typically does not cause numbness of the entire face, nor does it cause persistent speech changes or hearing difficulties. If the patient’s symptoms were due to hyperventilation, they should have resolved once the hyperventilation stopped. A reasonable re-evaluation of the patient would have picked up on the absence or persistence of the patient’s symptoms. The defense’s use of hyperventilation as an explanation for the patient’s new symptoms seemed uncompelling.

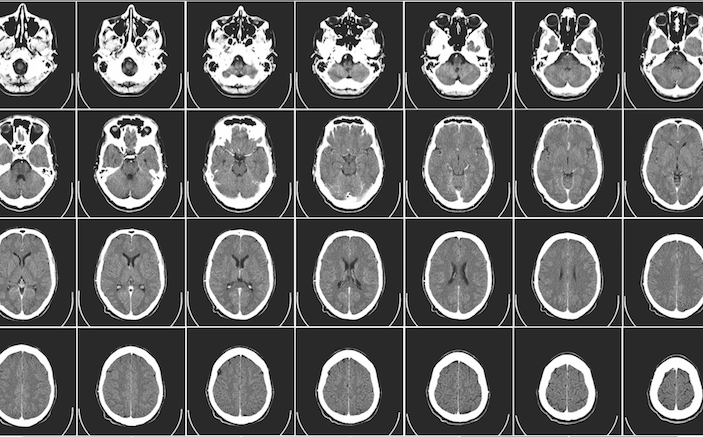

Another point of contention in this case was the emergency physician’s misread of the CT scan. Although a dense basilar artery sign is an uncommon finding, the consequences of missing this finding are potentially serious. Emergency medicine residency training has comparatively little formal training in CT interpretation. Without sufficient training or demonstration of competence in formally interpreting CT scans, a hospital may be called into question for credentialing a physician to perform such interpretations. Real-time radiology interpretations are ubiquitous in emergency medical practice and are available via teleradiology 24 hours a day to any location with an internet connection, so real-time readings by a radiologist would have been available in this case. If physicians practice outside of their specialty training when providing medical care, the law generally holds them to the standards of the specialist. Here, the emergency physician’s interpretation of the CT scan would be held to the standards of a radiologist – and a radiologist picked up on a critical finding that the emergency physician missed. Of course, the radiology interpretation did not occur until the following morning by which time the radiologist would have known the results of the MRI prior to interpreting the CT scan, giving the radiologist additional information that the emergency physician did not have at the time of the reading. While Brady argues that a determination whether this is a reasonable practice may depend on community or hospital practice patterns, few courts still accept the a “local” standard of care, instead recognizing a national standard to which all physicians are held.

In order to be successful in a medical malpractice lawsuit, a plaintiff must prove four elements: Duty to treat, breach of duty, causation, and damages. In this case, there was obviously a duty to treat and there were obviously significant damages since the patient suffered a debilitating stroke. Even if we assume that the treating emergency physician acted unreasonably, the plaintiff still must prove the that the physician’s negligent acts caused the patient’s injuries in order to be successful in a medical malpractice claim. Consider the timing of the events. The patient presented with a headache that had been present for four hours before she came to the emergency department. If a CT scan was ordered shortly after the patient was evaluated in the emergency department, a reading would ideally be returned within the first 30 minutes. If the basilar artery stroke was diagnosed at that time, the patient would already have been at least 4½ hours into the stroke process, putting her outside of the treatment window for thrombolytic therapy. Shortly thereafter, the patient became somnolent and had no improvement with Narcan.

The scenario noted that the patient underwent a thrombectomy nine hours after she presented to the emergency department which was 13 hours after her symptoms began. The BASICS study [5] showed that of patients who developed “severe” symptoms (defined as coma, locked-in syndrome, or tetraplegia), only 39 of 347 patients were able to look after their own affairs without assistance (modified Rankin Scale of 2 or less) at one month. By the time this patient received treatment, her comatose condition would have classified her as “severe” symptoms and therefore, even though she needed a walker to ambulate, her outcome was better than 89% of patients presenting with a severe basilar artery stroke. A 2002 study by Devuyst [6] showed that 100% of patients with basilar artery strokes and consciousness disorders had a poor outcome. A 2009 study by Goldmakher [7] showed that a dense basilar artery sign on CT increased the likelihood of a poor outcome more than fivefold. This patient’s outcome was therefore better than would normally be predicted based on her symptoms and radiologic findings.

To summarize, initially treating a patient with pre-existing migraine headaches and atypical symptoms as a migraine with aura may not have been optimal care, but I think it was arguably reasonable care. It is difficult to determine whether the physician performed any re-examination of the patient prior to discharge, but one was not documented and in a patient presenting with these complaints, that crossed over the line into unreasonable care. I also think that, in the absence of specialty training, it is unreasonable for a hospital to expect an emergency physician to interpret CT scans to the competency of a radiologist. However, even though aspects of this patient’s care appeared to be unreasonable to me, the plaintiffs would probably have had difficulty in proving that any perceived negligent care caused the patient’s damages.

REFERENCES

- https://www.ichd-3.org

- https://www.acep.org/clinical—practice-management/clinical-policy–critical-issues-in-the-evaluation-and-management-of-adult-patients-presenting-to-the-emergency-department-with-acute-headache

- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-workup#c8

- Detsky M, McDonald D, et al., Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging?, JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296(10):1274-83.

- Schonewille, et al., Treatment and outcomes of acute basilar artery occlusion in the Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): a prospective registry study. The Lancet, Neurology, 2009 Aug. 8(8), p724–730

- Devuyst G, Bogousslavsky J, Meuli R, et al. Stroke or transient ischemic attacks with basilar artery stenosis or occlusion: clinical patterns and outcome. Arch Neurol. 2002 Apr. 59(4):567-73

- Goldmakher, et al., Hyperdense Basilar Artery Sign on Unenhanced CT Predicts Thrombus and Outcome in Acute Posterior Circulation Stroke. Stroke. 2009 Jan. 40(1)