Our refrigerator used to be a collection of pictures and magnets. Drawings and papers with “A+” would flop back and forth as the refrigerator doors opened and closed. Over time, the drawings and papers became fewer, and we added a whiteboard with a dry-erase marker. At first, we used the dry-erase board for writing grocery lists and notes.

As our kids got older, it became a place for writing memorable quotes. My kids are all adults now, but they still remember many of the quotes from our refrigerator. Sometimes they’ll say, “I hate that quote,” when I remind them how it may apply to some current problem in their lives. However, it makes me proud when they recall some quotes and apply them to their own experiences.

Some of my favorites over the years included, “Life is 20% what happens and 80% how you react,” and “What you allow will continue.” Recently, one of my daughters put up a suggestion to “Take a breath. You don’t know what other people are going through.”

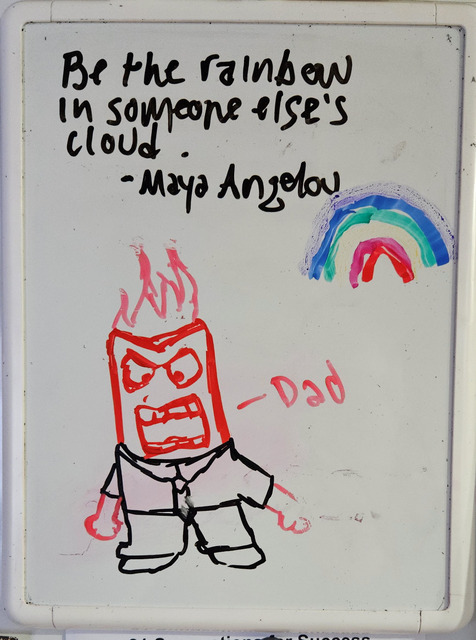

As I was packing up food for my overnight ED shift, I glanced up and noticed the latest nugget of wisdom: “Better to admit that you walked through the wrong door than to spend your life in the wrong room.” Thought-provoking. I liked it even more because it showed me how introspective those little kids have become. Of course, my youngest daughter had to include a caricature of me yelling at the television while watching college football playoffs. How the finger painting has progressed.

When I arrived at the hospital, I started my shift in a good mood. It was busy. Many patients were waiting to be seen as we were in the midst of COVID and influenza season. A recent surge in norovirus added to the chaos with multiple patients having intractable vomiting and diarrhea.

My first patient was in her 70s, brought to the emergency department by her daughter because she couldn’t keep down any food or fluids. She had been vomiting all day with a few episodes of diarrhea. Her vital signs were stable, which was a good start. I introduced myself and began asking about her history. When I asked how long this had been going on, she rolled her eyes and nodded towards her daughter, who explained that her mother couldn’t tolerate any food or fluids all day and was starting to have diarrhea.

I asked if she had any abdominal pain, and she again nodded towards her daughter, who was getting frustrated. “Mom, I don’t know. Were you having abdominal pain or not?” The patient raised her voice and said, “Noooo – wuh.” Gathering the rest of her history wasn’t much easier, so I decided to ask a brief review of systems to ensure there were no other issues. When asked about her history, she said, “It’s in the chart.”

She was bundled in several layers of clothing, so I asked her to remove her jacket and sweater so that I could better examine her. She rolled her eyes and asked, “Is this really necessary?” I smiled and said, “Unfortunately, it is.” She sighed and sat there for a moment. I told her, “I’ll go see another patient while you get undressed. Here’s a blanket and a gown. It would be a big help if you could do that for me. Meanwhile, a nurse will come in to draw a couple of blood tests and start an IV.”

I left the room, took a few deep breaths, and went to see the next patient, who also had vomiting and diarrhea. It was going to be one of those nights. After placing orders for a couple of patients, I returned to examine my first patient. She was now in a gown with a blanket over her, arms crossed, and berating the nurse who had just started her IV.

“I’m not sure why it took you three sticks to get this IV. It isn’t like you can’t see my veins.” I started my exam by looking in her mouth. She immediately questioned why I was looking in her mouth when she was having vomiting, not mouth problems. I explained that I wanted to check her throat and get an idea of her hydration status by seeing how moist her mucous membranes were. She rolled her eyes and shook her head. I listened to her heart and lungs, asking her to take deep breaths, which she did reluctantly. Then I tried to examine her stomach, but she kept her arms folded, making it difficult.

At that point, I had enough. Remember: What you allow will continue. I started thinking about how I would phrase my rebuke. I couldn’t just yell at her, but I had to let her know that her attitude was unacceptable. “Listen, I’m here to help you. You came to see me for help. I don’t know why you’re upset with me when all I’ve done is try to help you. Do you have another problem?”

That seemed a bit harsh, so I thought of a more direct approach. “Why are you so angry with me? I’m just trying to help you.” That seemed more appropriate. I looked back at her, and then remembered one of the quotes on our kitchen whiteboard: “Take a breath. You never know what other people are going through.” I bit my tongue, smiled, and examined her abdomen as best I could, telling her, “A lot of people have these same symptoms right now. We’ll give you some IV fluids and medications, and I think you’ll feel much better. We’ll also do some blood tests to check your electrolytes. I’ll check back on you in a little bit.”

I saw a few more patients and checked on lab tests. One patient had a potassium of 2.6. Another had an acute metabolic acidosis with a bicarbonate level < 5 and a significantly elevated anion gap. These patients were sick! Fortunately, all the lab testing on my first patient was normal. She received antiemetics, an antispasmodic, and IV fluids. When I returned to check on her, she smiled. She was in a lot less pain. I told her, “Your blood tests are normal, and if you’re feeling better, I’ll send medications to the pharmacy to help with your symptoms. I want the nurse to give you some fluids to ensure you can keep them down before you leave. If that’s good, we’ll get you home so you can rest.”

“That would be wonderful, thank you,” she replied. I did a side-eye, thinking “Who are you, and what did you do with the other lady who was sitting on the bed an hour ago?”

She received a glass of diluted apple juice and tolerated it well. I stopped back in to see if she had any other questions. When I entered the room, she held out her hand. I went over, and she pulled my hand to her mouth and kissed it. “Thank you for making me feel better,” she said. Wow. Her daughter explained that her father (the patient’s husband) had recently died, several family members had visited, and the patient likely got sick from her grandchildren. She was frustrated because she had to run so many errands related to her husband’s death and her family’s visit, and she thought her illness would prevent her from getting anything done.

We really don’t know what other people are going through.

“I’m glad you’re feeling better, and I’m deeply sorry for your loss. I hope the new year brings you strength and support from your family. And I hope you can look back with happiness on all the wonderful times you had with your husband.”

I returned to the computer, sent her prescriptions to the pharmacy, and took a deep breath. I had a long night ahead. But I also scribbled a reminder on a piece of scrap paper to change the refrigerator quote.

“Be the rainbow in someone else’s cloud.”

– Maya Angelou