The Case

A 65-year-old male presented to the emergency department out of concern for bleeding from a lump at his right groin. The patient reported he had a lump at the location of his right groin for several months but was previously smaller, approximately golf ball- sized compared to how it appears today.

The patient’s wife pointed out to him this morning that blood was on the bed sheets, and he subsequently noted bleeding from the surface of the skin at the location of the lump. He also noted this lump had grown significantly larger since the prior evening. He endorsed discomfort to the same area, but said it was not painful. He noted a tingling sensation in his right foot that was new as of waking up today.

The patient had a past medical history of hypertension, severe peripheral vascular disease including an aortic bifemoral bypass 12 years ago and with thrombectomy of bilateral femoral arteries seven years ago. He admitted to current tobacco use. His current medications included Plavix, lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide and pravastatin.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable with the initial vitals of BP 172/101, HR 95, 100% Rm Air, RR 20, Temp 36.9 C with a weight of 64.3 kg. He was in no acute distress but was anxious appearing. He was awake, alert, and oriented. HENT exam was unremarkable. His lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally with no signs of distress. His heart rate was borderline tachycardic with no rubs, gallops, or murmurs noted.

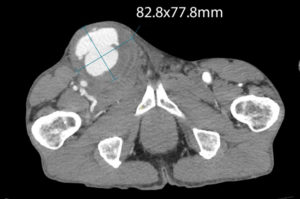

He had no CVA tenderness, and his abdomen was soft, nontender, without masses or signs of peritonitis. He had bilateral DP and PT pulses that were equal and 1 plus. He was neurologically intact with normal sensation at both dorsal and plantar aspects of his feet bilaterally with strength 5/5 with dorsiflexion and plantar flexion bilaterally. He had a large circumferential, raised pulsating mass as the location of the right femoral triangle/inner groin that was approximately 6-7 cm in diameter that corresponded to his heart rate on telemetry and palpable pulse with each pulsation.

Notably, bright red blood was appreciated over the surface of the mass, and it appeared to seep from cutaneous pores over the suspected aneurysm (figure 1).

With a high suspicion for femoral artery aneurysm on the patient’s initial presentation, bilateral antecubital IVs were established, and vascular surgery was immediately consulted. Laboratory workup was obtained and sent with BMP, CBC, Type and Screen, PT, INR and PTT. His PT was within normal limits (WNL) and INR slightly elevated to 1.13.

His PTT was WNL. BMP was unremarkable. His CBC did demonstrate anemia but with a hemoglobin of 12.7 (baseline history CBC was consistently 9-10) as well as hematocrit pf 37.8 (baseline approximately 29-32).

To reduce wall tension, the patient was immediately begun on an esmolol bolus and infusion for heart rate reduction as well as nicardipine infusion to lower blood pressure. He was given a bolus of 35 mg of esmolol and initially titrated to 50 mcg/kg/hr with an initial nicardipine infusion at 5 mg/hr. Imaging with CTA abdomen aorta with leg runoff was ordered at request of the vascular surgery team who agreed to evaluate the patient at the bedside.

The patient’s blood pressure was gradually lowered over the course of the next hour while an OR was being prepped with nicardipine incrementally increased in 2.5 mg infusion rates from 5mg/hr to a maximum of 15 mg/hr. The patient’s heart rate was simultaneously lowered with titration of esmolol, beginning at 50mcg/kg/min after the initial bolus of 35 mg and maxing out at 300 mcg/kg/hr. He was given analgesia with 50 mcg of fentanyl IVP to help facilitate this as well.

His heart was maintained at 80 with this intervention and BP was lowered to 138/83. An additional 5 mg metoprolol was given to achieve a target heart rate of less than 60, and systolic BP of less than 120, and subsequently achieved a BP of 117/76 with a heart rate of 71 before being taken emergently to the OR for surgical intervention.

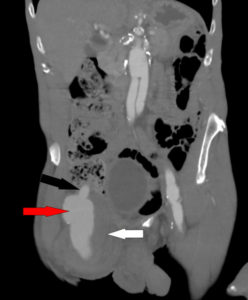

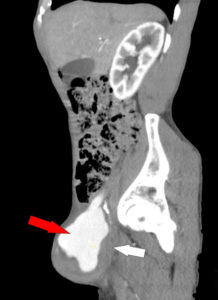

CTA runoff imaging was significant for a large right common femoral pseudoaneurysm with active extravasation of aortofemoral bypass measuring 75.8x 86.9mm (figures 3-7).

The patient underwent ilio-profunda bypass after confirming a ruptured false aneurysm in the OR where it was resected, and an ilio-profunda bypass graft was placed after an open preperitoneal exploration of the common iliac artery and was discharged five days later and prescribed Plavix 75mg daily.

On outpatient follow up, the patient did experience complications of wound dehiscence and breakdown subsequently requiring debridement.

Discussion

The literature on femoral aneurysms is limited to case reports and techniques to vascular surgical interventions. Medical management guidelines of these patients preoperatively are very limited. Rupture is catastrophic, occurring once the stress on the vessel wall exceeds its tensile strength, with larger aneurysms more likely to rupture.[1]

The primary goal of medical therapy is to decrease the force of left ventricular contraction and systemic blood pressure, which are the main determinants of extension and rupture. β-Blockers first, other antihypertensives such as vasodilators, and adequate analgesia should be initiated to keep systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg and heart rate <60 bpm.[2]

Potential complications include expansion, rupture, embolization, extravasation with arterial wall compression, blue toe syndrome and leg ischemia.

Femoral pseudoaneurysm can typically be caused by any form of percutaneous intervention that uses the femoral artery as their entry point. Classically, interventions after cardiac catheterization for coronary stenting have been implicated. However, any form of femoral artery cannulation may be the culprit.[3]

Resources:

- Cline D.M., & Ma O, & Cydulka R.K., & Meckler G.D., & Handel D.A., & Thomas S.H. (Eds.), (2012). Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine Manual, 7e. McGraw Hill. https://accessemergencymedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=521§ionid=41068918

- Tsai TT, Nienaber CA, and Eagle KA. Acute Aortic Syndromes. Circulation. 2005;112:3802–3813

- Tulla K, Kowalski A, Qaja E. Femoral Artery Pseudoaneurysm. [Updated 2022 Dec 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493210/