Humeral shaft fractures have long been a diagnostic and treatment conundrum for emergency physicians. Definitive treatment can be highly variable and predictions in the ED seem near impossible. Here’s an illustrated guide to the anatomy, treatments and complications of this common emergency.

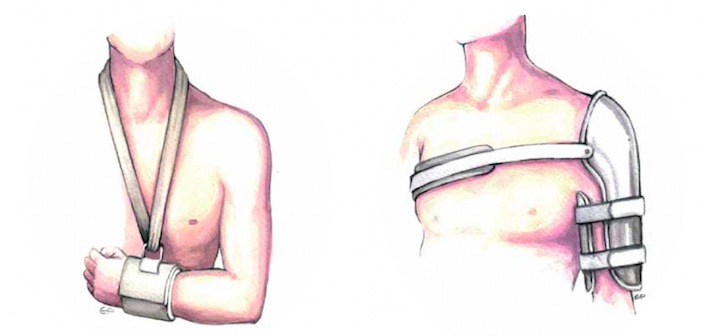

One of the remarkable characteristics of humerus fractures is their dramatic radiographic appearance. We are often alarmed when our orthopedic colleagues seem to minimize these fractures or recommend non-operative treatment. A hanging cast, sling and swathe, coaptation splint, or simple sling all seem like ridiculously simple treatment options.

In this article I will briefly review anatomy as it pertains to injury and treatment, explore the indications for operative and closed reduction, discuss the evolution of immobilization techniques, and identify emergency complications associated with fracture patterns. I will also provide background and data to better understand the decision making of our orthopedic colleagues. This information, in turn, will help you better educate and reassure your patients.

Anatomy and Deforming Forces

The most pertinent anatomy may not be seen on X-ray. The deforming forces of the muscles and tendons predict angulation, displacement, and potential difficulties with closed reduction. The neurovascular structures coursing around the humeral shaft are the most important anatomic considerations.

Anatomically deforming forces are defined relative to the fracture location. Fractures that occur proximal to the pectoralis major insertion have a proximal fragment that is abducted and externally rotated. This is because the rotator cuff muscles insert proximally and abduct and externally rotate the proximal fragment. These fractures can be difficult to reduce and maintain because of their proximal location and the deforming force of the rotator cuff muscles

Above Deltoid insertion but below Pectoralis insertion. The pectoralis insertion is actually surprisingly high on the humerus. Fractures that occur between pectoralis insertion and deltoid insertion pull fragments in opposite directions. The deltoid pulls the distal fragment laterally while pectoralis pulls the proximal fragment medial toward the body.

Fractures that occur distal to the insertion of the deltoid muscle tend to have a proximal fragment that is abducted by the deltoid and a distal fragment that shortens due to the biceps and triceps contraction. The distal fragment may also be a bit anterior since biceps are stronger then triceps. These fracture patterns may present difficulty maintaining length after reduction and splinting.

The most important anatomic considerations are the peripheral nerves of the upper arm. Proximal fractures may affect any aspect of the brachial plexus, but the single most common nerve injury involves radial nerve, about 10-18% of humeral shaft fractures. The radial nerve is so named for its distinct spiral path coursing around the shaft of the humerus. Proximally, the radial nerve innervates the triceps, brachioradialis, and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) muscles, and a small branch that goes to anconeus. As it gets closer to the elbow it splits into three branches. One branch is the posterior interosseous nerve, which innervates pretty much all of the wrist extensors located in the dorsal aspect of the forearm. The next branch is a dedicated branch to the extensor carpi radialis brevis, and the third is the dorsal sensory branch of the radial nerve, which is entirely sensory with no motor function. The most common nerve deficits associated with humeral shaft fractures are an inability to extend the thumb, inability to extend the wrist, and decreased sensation over the dorsal aspect of the hand.

Nerve testing in the setting of midshaft humeral fractures is quite straightforward. Go through your basic motor and sensory testing of the median and ulnar nerve. Next, test the triceps function which will be limited due to pain, but gentle resisted force can be appreciated with contraction of the muscle without displacing the fracture. The real focus of the exam should be given to the radial nerve. Check the thumbs up “hitchhiker sign”, (which I used to call the Fonzie sign until about half of my patients responded with blank stares clueless as to what or who I was talking about). Next, test extension of the wrist, and sensation over the dorsal aspect of the hand mainly on the dorsum of the thenar web space.

Mechanism and Presentation

Most humerus fractures occur in the elderly and result from simple falls onto the humerus. Direct impact typically results in comminuted fractures while a fall on outstretched extremity will more likely result in spiral or oblique fracture patterns.

Fractures in younger patients are more likely to be the result of high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle accidents or gunshot wounds. A low energy mechanism in a young patient should raise suspicion for pathological fracture, either benign or malignant. Among the more common benign lesions leading to pathologic fractures in children and young adults are unicameral bone cysts. There are also a number of malignant lesions that can occur. In elderly patients, multiple myeloma and metastatic disease are often the culprits and fractures can result from simply putting on clothes or lifting a plate of food. It’s not necessary for the ED physician to identify what the underlying lesion is, but maintain suspicion and identify a pathologic fracture.

Gross deformity is usually evident, but in subtle fractures the arm may appear aligned and pain localizes only to the elbow or shoulder. Because localization poorly correlates with the fracture location, X-rays of the humerus with elbow and shoulder included are appropriate.

Holstein Lewis Fractures

Holstein Lewis fractures involve the distal third of the humerus – where the radial nerve spirals around from the posterior aspect of the humerus – with a high incidence of associated radial nerve palsy. Some orthopedic surgeons do not feel as though Holstein Lewis fractures respond well to functional bracing and should instead undergo operative intervention. That said, there is convincing data to the contrary and my experience has been that most orthopedists manage these fractures in the exact same way as all other humeral shaft fractures.

Closed vs Open treatment

Closed vs. open: that is the question. The easiest way to approach this is to understand the very clear indications for surgery. The list requiring emergent surgery is short: Open fractures, compartment syndrome and vascular injury. It’s surprising what can wait in regards to surgical intervention.

The next category focuses on indications for acute surgical intervention, meaning the patient should probably be admitted and have surgery during the hospital stay.

Admission for Surgery

- Multiple other traumatic injuries

- Floating elbow (concurrent fractures in the forearm and humerus)

- Segmental fractures

- Displaced intra-articular shoulder or elbow involvement

- Bilateral humeral fractures

- Progressive neurologic injury

- New nerve or vascular injury after reduction

- Pathologic fractures

- Unacceptable alignment following closed reduction

All of these fractures warrant orthopedic consultation from the emergency department or at a higher level of care. Note that the last one is “progressive neurologic injury” implying that the deficit is progressively worsening over time. Not all fractures with nerve injuries require operative intervention.

Some patients will undergo delayed surgical intervention. These patients might be discharged home but undergo surgical intervention at later time for any of the following reasons:

- Delayed surgical intervention

- Poor pain tolerance

- Inability to perform activities of daily living

- Delayed nerve palsy

- Non-union

- Delayed union

- Loss of reduction

The history of interventions and outcomes in humeral fracture fixation helps clarify why orthopedic treatment decisions appear so varied. Originally, fracture fixation involved a large incision with bridge plating. The problem with open reduction and internal plate fixation is that the dissection mobilizes the brachial plexus and/ or the radial nerve. In my previous orthopedic life, attendings would yell at residents to “not even look at the nerve wrong”. The radial nerve is very finicky. Gentle retraction during surgery can result in a long lasting neuropraxia. Even with delicate surgical technique many patients develop radial nerve palsy post-operatively. Subsequently, greater emphasis is now given to non-operative treatment. A large study done by the still living pioneer of orthopedic surgery, Augusto Sarmiento, demonstrated excellent outcomes with functional bracing which became the accepted treatment for simple mid-shaft humeral fractures.

With the development of humeral intramedullary nails, many orthopedists thought this approach would minimize post-operative radial nerve complications. Unfortunately, intramedullary fixation continues to have a high incidence of nonunion and rotational deformity.

Today, a great deal of debate over the preferred method of open treatment remains. There is significant variability among orthopedists’ individual threshold to pursue operative intervention. For the ED physician, the above outlined indications offer at least a good guide for communication with the patient and the consultant.

I emphasize the complexity involved in treatment decisions because so many patients have a “just fix it” mentality. As ED physicians we are the patients’ first point of contact and it’s important that we guide expectations in parallel with our orthopedic colleagues. Patients are often appalled at the idea of non-operative intervention especially when they see their dramatic X-rays. If the orthopedist is not available to explain the reason for the treatment method, the emergency physician can provide the risks and benefits of operative or non-operative treatment, and explain that treatment methods vary.

Orthopedic Consultation

Obviously fractures warranting emergency intervention require immediate orthopedic consultation or transfer to a facility with on call orthopedics. When orthopedic surgery is on call at your facility, it’s reasonable to consult on any displaced or angulated fractures, or any fractures with associated nerve palsy. Don’t be surprised if the surgeon opts for non-operative treatment even in the presence of a stable radial nerve palsy. Unless fractures meet one of the above acute or emergent criteria, immobilization, pain control and discharge may be reasonable. This is when a thorough understanding of the risks and benefits of surgical intervention becomes beneficial. Patients may have different expectations and can feel as though their treatment is being mismanaged or minimized when they don’t see an orthopedist and find themselves being discharged home in an archaic-looking coaptation splint or cuff and collar.

For the emergency physician, understanding the indications for emergent, non-emergent and delayed surgery also helps our orthopedic colleagues define their care plan. When we fail to communicate the pertinent indications for admission or surgery, the orthopedist on call may resist hospital admission. Clearly communicating that the patient suffers from poly trauma, is unable to perform activities of daily living, or any of the other indications for admission, helps the orthopedist better understand the potential need for surgery.

Non displaced fractures with completely normal alignment, meeting none of the above mentioned criteria for admission or surgical intervention, can be discharged without orthopedic consultation so long as they have orthopedic follow up within the week and are given through discharge instructions, return parameters, and follow up instructions. If you have a good relationship with your orthopedic colleges or a voice on the orthopedic committee it’s reasonable to clarify the circumstances in which these patients can be immobilized and discharged without consultation.

For ED physicians practicing without orthopedic consultation available, transfer is indicated when any of the emergent or acute indications for surgery are identified. Displaced fractures not meeting the criteria of acceptable alignment should be reduced and splinted prior to discharge. If the ED physician is concerned, orthopedics at a higher level of care can be contacted through a transfer center. Even if transport and admission are not indicated, reliable outpatient follow up can be arranged. If the patient is being transferred its reasonable to communicate with the accepting orthopedist whether reduction should be performed prior to transfer.

Reduction

Our orthopedic colleagues will frequently ask that we perform reduction to correct angulation. Reduction does not require any special or unique technique. As with all fractures, gentle traction is necessary to release the spasm of deforming muscular forces. Aggressive reduction can result in new radial nerve palsy so gentle traction is the first step. For the overwhelming majority of patients, this is sufficient to adequately reduce most fracture patterns. For deformities requiring more than gentle traction, stabilizing above and below the fracture allows enough leverage to gently correct the deformity.

Radial nerve palsy is not a contraindication for closed reduction. In some regards reduction is easier when the patient already has a radial nerve palsy because you’re unlikely to make it worse. In all circumstances it’s critical to document pre and post reduction neurovascular status.

Rotational deformity is poorly tolerated in any long bone fracture and needs to be corrected. Anterior and varus angulation, however, are surprisingly well tolerated. When describing fracture angulation, it is always described relative to the distal fragment. So, if the distal fragment is anterior to the fracture site then the fracture has anterior angulation. Because the biceps is stronger than the triceps, anterior angulation is one of the most common findings. A surprising amount of anterior and varus angulation can be accepted without correction. Twenty degrees of anterior angulation can be tolerated in moderate functioning individuals without significant functional impairment resulting. Low to moderate functioning individuals will also tolerate up to thirty degrees of varus angulation and up to 2cm of shortening. Because most patients suffering from these injuries are moderate to low functioning elderly individuals, angulation according to the above parameters is usually acceptable. Obviously in a professional athlete or anyone who depends on their upper arm function for their livelihood, minimal angulation or displacement is ideal.

Reduction may require sedation since nerve block or hematoma block are difficult in the upper arm. Sedation really depends on patient’s pain tolerance. When gentle traction is all that is required, this can often be tolerated with narcotic pain medication alone.

Reduction itself usually involves simply pulling the fracture out to length, or correcting the rotational or angular deformity. Don’t be surprised if you lose reduction to some degree when traction is released. The deforming forces are difficult to stabilize in immobilization. So long as gross deformity or skin tenting is corrected, rotational deformity is corrected, and post reduction X-Rays meet the above mentioned criteria, consider your reduction acceptable.

Disposition

The above mentioned indications for surgery are relatively straightforward. As with all consultants, there will be some orthopedists who are more aggressive and others who are less so. Patients not meeting the above mentioned surgical criteria can typically be discharged home with orthopedic follow up within a week. In addition to the emergent and acute indications for surgical intervention, some patients will need to be admitted simply for pain control or an inability to function. Patients with multiple co-morbidities may be poor candidates for surgery but may also be unable to functioning in their homes such that admission for placement in higher care or rehabilitation may be indicated.

One of the most difficult facets of disposition involves alleviating fear, offering reassurance, and instilling confidence in the discharge plan. This will become a recurring theme in the era of healthcare reform. Without adequate explanation, patients may feel minimized or dismissed. The best approach is detailed and thorough communication. It’s also important to explain that different fractures tolerate varying degrees of angulation and or displacement. Patients seem initially horrified by the concept that a fracture fragment can move to some degree and may not understand the concept of functional tolerance. Explaining that some degree of angulation is accepted because it does not affect day-to-day activity can be reassuring.

It’s also important to discuss immobilization. In today’s era of smartphones and tablets, a cuff and collar seems archaic. Explaining the difficulty in maintaining immobilization along with the drawbacks of other available options is helpful. Perhaps more importantly, patients should understand that what they receive in the ED would not be their long-term definitive immobilization. Explaining what a Sarmiento brace is and that the patient will be converted to a more stable and adjustable form of splinting offers additional reassurance.

Illustrations by Erika Pasciuta, MD

2 Comments

great

Thanks Deidre!