As I was building an ultrasound lecture for emergency medicine (EM) and reviewing materials in the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Ultrasound Section, I came across an ACEP newsroom article that raised some concerns.

The article discusses the diagnostic criteria for pericardial tamponade, including the variation in mitral and tricuspid valve inflow velocities during respiration. While I found the article generally well-written and succinct, the authors’ suggestion that the respirophasic variation thresholds should be higher than those recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) troubles me.

For those without significant ultrasound training, doppler inflow velocity of the mitral and tricuspid valves is an essential echocardiographic measurement used to assess diastolic function and filling pressures in the left and right sides of the heart. It is obtained using the “pulse wave doppler” function on ultrasound and measurements are generally obtained in the apical 4 chamber view.

It consists of both an “E-wave,” which is a measurement of the passive early inflow of blood from the atria into the ventricle in diastole as well as an “A-wave,” which is a measurement of atrial systole and constitutes the latter portion of ventricular diastolic filling. When pericardial fluid accumulates around the heart the transmitted pressure during respirations can change the speed of the E-wave velocity. When this “inflow variation” reaches a certain threshold it is known as “pulsus paradoxus by echo.”

Now here’s the quote from the ACEP newsroom article that caught my attention: “While other sources say the mitral valve needs greater than 25% variation, and the tricuspid valve needs greater than 40% variation for tamponade, using 30% and 60% respectively will increase specificity.”

This assertion frustrates me because it endorses a diagnostic shift toward increased specificity at the cost of sensitivity, which could have dangerous consequences in the fast-paced, high-risk world of emergency medicine.

Let’s break this down. According to ASE guidelines, a mitral E wave inflow velocity variation of greater than 25% is sufficient to diagnose early pericardial tamponade by echocardiography. These are standards we rely on, standards rooted in a balance of sensitivity and specificity. Why then, would we want to increase the threshold to 30% for mitral inflow and 60% for tricuspid inflow? Yes, this might increase specificity, but at what cost?

As emergency physicians, our primary responsibility is to identify life-threatening conditions quickly and involve the appropriate specialists when necessary. In a litigious and high-stakes environment, the idea of recommending increased specificity—thereby decreasing sensitivity and potentially missing more cases—raises red flags.

Normal respirophasic variation exists in healthy patients, but the thresholds for diagnosing tamponade are well-established. A mitral E-wave inflow velocity of greater than 25% should be sufficient to flag tamponade. By increasing this requirement, we risk missing a condition that, if left untreated, could quickly lead to cardiopulmonary collapse. This shift in diagnostic criteria seems misaligned with our core mission in EM: identifying threats to life early and accurately.

In fact, many of our EM guidelines already lean toward sensitivity over specificity, precisely because we cannot afford to miss critical diagnoses. A great example is the emergency department’s approach to beta-hCG levels in suspected ectopic pregnancy, which differs from the recommendations of ACOG, reflecting a more cautious and inclusive threshold to ensure we don’t miss life-threatening conditions.

So, I have to ask the authors of this article: What is the rationale behind advocating for increased specificity at the risk of decreased sensitivity when it comes to diagnosing pericardial tamponade? In my view, this recommendation not only places our patients at risk but also potentially exposes emergency physicians to legal liability for missing a life-threatening condition that could have been identified under the existing ASE guidelines.

Here are two cases to underscore my argument:

Case 1:

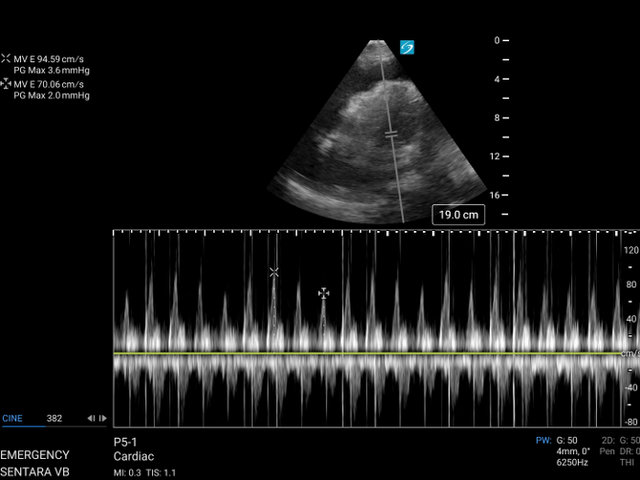

A 60ish-year-old female presented to the emergency department with acute right flank pain, shortness of breath, and hypotension. She was 10 days post-op from cardiac surgery. Bedside ultrasound revealed a large pericardial effusion with right ventricular free wall collapse during diastole, consistent with tamponade physiology.

Notably, there was a 26% variation in mitral E velocity, which under the current ASE recommendations further supported the diagnosis of Tamponade. This patient went emergently to the Cath lab with significant improvement of her cardiovascular status after pericardiocentesis.

A subxipoid view of the heart with a very large pericardial effusion demonstrating significant right ventricular (and right atrial) collapse during diastole.

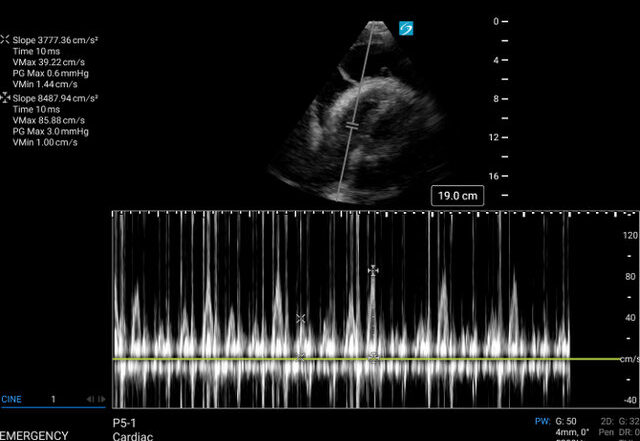

Image 1: An apical 4 chamber view of the heart. Pulse wave doppler measurements of the mitral E-wave inflow velocities. The sweep speed has been adjusted to allow for over 20 heart beats and providing better visualization of the respiratory variation in inflow velocities. Note the variation of 25.9% between peak inspiration and expiration.

Case 2:

A 78-year-old male with a history of severe COPD who presented to the emergency department with hypotension, tachycardia, and progressive dyspnea. Despite being on a regimen of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators, the patient’s condition had deteriorated, with increased oxygen requirements and worsening fatigue.

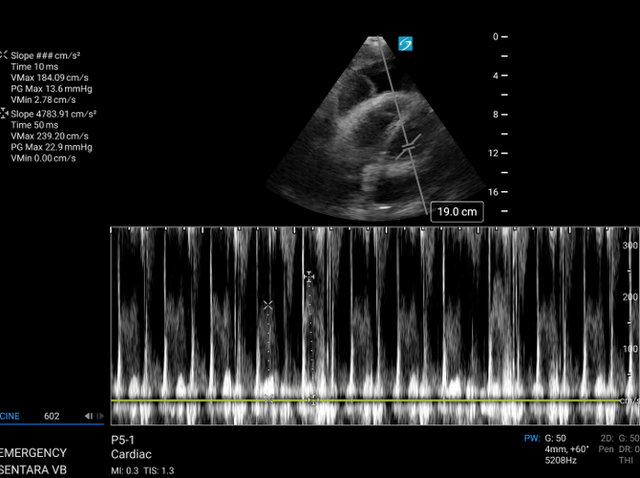

A point-of-care echocardiogram performed during the evaluation revealed a very large pericardial effusion. The echocardiogram also demonstrated: Left ventricular diastolic collapse, this rare finding indicated severe hemodynamic compromise. Right ventricular diastolic collapse, consistent with cardiac tamponade. Mitral and tricuspid pulse wave doppler inflow variation denoting pulsus paradoxus by echocardiography.

RV inflow variation 54%

LV inflow variation 23%*

*In this case the patient’s cardiac windows and respiratory distress prevented optimum angles for pulse wave doppler inflow variation but still should serve to highlight the folly of the increased cutoffs for inflow variation proposed by the authors.

In both of these cases we can see significant collapse of the ventricle(s) during diastolic filling with large pericardial effusions. In both of these cases we can also see inflow variation that does not meet the proposed thresholds by the authors of the ACEP newsroom article.

I cannot in good conscious agree with the recommendations of an increased threshold at the cost of decreased sensitivity. The bottom line is this: In emergency medicine, it’s better to cast a wider net when life hangs in the balance. Our job is to protect our patients, and that often means prioritizing sensitivity. Let’s not lose sight of that.

Responding to this article:

https://www.acep.org/emultrasound/newsroom/may-2024/cardiac-tamponade