When it comes to treating children with shock, it can be worthwhile to spend a couple minutes scanning for unusual etiologies.

It had been a reasonably quiet morning shift in your ED until the hospital’s on-campus pediatric clinic called regarding a patient in transit. They are sending a 6-year-old girl who presented with a chief complaint of fever. The attending pediatrician is unable to provide much history but reports a fairly abrupt deterioration of the child’s status during the resident history and physical examination.

On arrival to the ED, the patient appears uncomfortable with reduced tone and activity. Her parents communicate their agreement that her condition worsened noticeably during the clinic evaluation. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 94/78 mmHg, heart rate 148, respirations 36 and temperature 104.30F. Her capillary refill time is 5 seconds and she appears pale.

It appears you are faced with a case of normotensive or “compensated” shock. Both her low pulse pressure and cold skin suggest profound vasoconstriction. Most of your staff has, quite appropriately, begun working on intravenous access while another nurse – an observer of your recent bedside diagnosis of an unsuspected pericardial effusion – hands you a curvilinear ultrasound probe.

In two previous issues of Soundings, we discussed multiple cases in which children presented with shock and emphasized how a systematic approach to scanning can be very useful. In this third segment covering pediatric resuscitation ultrasound, we will present a frequently neglected consideration in the child with undifferentiated shock.

You begin, as usual, by assessing the heart. It is small, appears morphologically normal, and contracts vigorously with no pericardial effusion present. Quickly, you rotate your probe and assess the inferior vena cava (IVC). It is small and collapses fully with inspiration. Your nurse asks you whether you would now like to administer 20 cc/kg of normal saline, pushed as quickly as possible.

In this case, your response is, appropriately, “Yes.” The “pump” is working and the “tank” seems near-empty. Improving perfusion is your foremost immediate priority.

While the fluid bolus is being administered, you apply a linear probe to the chest wall and quickly scan multiple lung segments. In addition to normal lung sliding and comet tail artifact you also observe the uniform presence of A-lines. Few or no B-lines are appreciated. The normal lung interstitium suggests vascular integrity and no third-spacing, at least to this point in the resuscitation.

Meanwhile, the fluid bolus has caused considerable improvement. The PICU has been contacted and a bed will be available soon. Your nurses, happy and relieved subsequent to another “save,” ask whether you would like to administer intravenous antibiotics subsequent to appropriate cultures of blood and urine pursuant to a diagnosis of sepsis.

At this point, the little voice in your head interjects, “could there be more to this?”

Your response to your nurses is, appropriately, “Yes, but I need to look around a little more.”

You now begin the extremely important task of searching for occult volume loss. Using a curvilinear probe, you begin by performing a traditional FAST (Focused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma) exam.

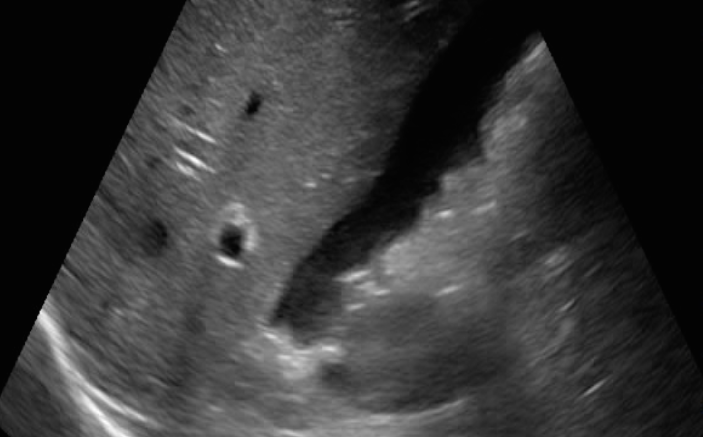

The right upper quadrant view is most definitely not normal. Fluid is clearly visible in the right paracolic gutter and Morison’s Pouch (Figure 1 – click image for video link). Moving to the left upper quadrant, you observe what appears to be some heterogeneity of the spleen (Figure 2). Proceeding further you also note free fluid in the pelvis (Figure 3).

It turns out that the child’s family recently returned to their stateside home following a two-week visit to Africa where the young girl met her grandparents for the first time. Her fever is due to malaria contracted during the visit. Subsequent to your stabilization, the resident working in the pediatric clinic volunteers that he palpated a very large spleen on his exam and was so impressed that he invited the clinic medical students to do the same. Not long after, the child was first noted to be pale and manifested other signs of shock.

Practitioners who are experienced in the care of patients with malaria admonish their trainees to palpate the spleen with the utmost of care. Rapid engorgement with distorted red blood cells causes the spleen to be very fragile and prone to injury. In fact, spontaneous rupture of the spleen is sufficiently common that this diagnosis should be suspected whenever a patient at risk for malaria presents with shock or abdominal pain.

Instead of going to the PICU, your patient goes with you to the CT scanner where a high-grade spleen injury is noted. Pharmacologic treatment for malaria is initiated while surgery is consulted. Subsequent to a period of bed rest the child’s condition improves while follow-up scans suggest healing of the injury. Surgery is avoided and she is discharged home and experiences a full recovery.

In a follow-up conference, you were asked why you chose to perform a FAST scan on a child presenting with fever and no history of trauma. Although tempted to allude to your extraordinary clinical judgment, you respond that you were trained to spend an extra minute or two to ensure against unusual etiologies of undifferentiated shock.