Society’s obsession with new political ideas – and even with freedom itself – can come at a cost. A dose of nostalgia may be helpful in reminding us to slow down and treat each patient with the unique human dignity that they deserve.

It is banal in the extreme to suggest we cannot live in the past. The arrow of time is hurling in only one direction. Black-hole theorists please take note of this: it’s never been proven to go the other way. But allow me some simple nostalgia to yearn for a time when patients respected their doctors, workers enjoyed some measure of security, families were intact, albeit dysfunctional, and disruption wasn’t just a business school buzzword.

It was Edmund Burke who pleaded with his contemporaries not to overthrow tradition in favor of new ideas or theories simply on the basis that they were new, exciting and different. I support Burke in proclaiming our era’s malady, like his, is not nostalgia but neophilia – the love of the new.

I’m in another period of rereading and reevaluating books and concepts from my past, which I probably did not understand when I first encountered them. I am more emotionally torn by Our Town, the play, today than I was when I first saw it in 1961. Cat On A Hot Tin Roof is even better now after decades of marriage.

In 1955, Walter Littmann’s book, The Public Philosophy, argued that the core commitment to majority rule and true free speech and respect for the individual requires an underlying moral consensus. Without such a consensus and absent objective moral truth, rights merely become political and can be redefined by what is fashionable in the moment. Some permanency is required.

I believe we cannot be ideologically diverse if everything is a political equation meant to lubricate squeaky wheels. Politics is chiefly a function of culture. Littman was convinced that: “An ideological secularism undermines liberalism and over the long haul cannot sustain a free society. We are by our adherence to progressive intellectualism killing ourselves and the western tradition.”

Irving Kristol said of his generation’s neo-conservatism: “We are all merely liberals who’ve been mugged by reality.” Any true conversation in the public square about the nature of man and society requires some agreement as to belief. I for one believe the Ten Commandments is not a bad place to start. Bring forth a better program for examination and I welcome the debate. Depth of convictions sustains the free society; not diversity, pluralism, tolerance or respect for newly invented rights. They are the fruits of liberalism, not the source.

So why this discussion now? Where is the emergency medicine take-home message? Simple. Over the past few days, I have counseled several families about their aging loved ones. They ranged from the barely sick to those with recent strokes and feeding tubes. Some had good neurological functioning while others had little to prove that there is thought or life left in their bodies. I can easily remember how difficult these discussions were in the emergency department, particularly in the heat of battle.

The dead and dying children were always the hardest for me. In the April 1998 issue of First Things, a statement was made by The Ramsey Colloquium, a diverse group of Jewish and Christian scholars led by Richard John Neuhaus. The group made a particular statement which has since stayed with me. While acknowledging that the “human rights” discourse is often misused they reaffirmed its value as a cross-cultural deliberation about the dignity of the human person. Let’s repeat that: not about people but the person. The center of the American Revolution was not about a group, a class, a race, a gender but about the individual person. Humanity comes to us in only one unit, one person at a time, one soul, one human to care for, to love, to aid in their time of pain and suffering. Just like in emergency medicine, we care for one unique entity at a time and by doing our best for that one person, we promote the concept of human dignity.

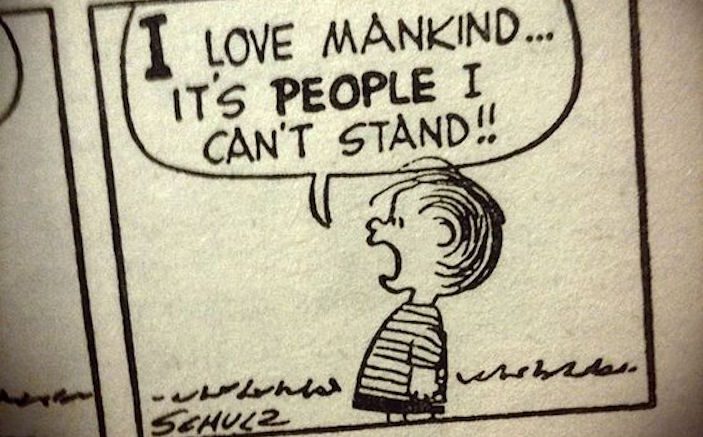

In the “Peanuts” comic strip many years ago, Lucy is trying to understand Linus – a sad-sack, hapless character I can relate to. Lucy declares: “You could never be a doctor! You know why? Because you don’t love mankind, that’s why!” To which Linus replies: “I love mankind. It’s people I can’t stand.”

Emergency personnel are one of the few groups of professionals that get no choice. We take each individual who has come in for an unplanned visit at what is often the worst moment of their lives. Rarely did they have the clairvoyant foresight to follow their mother’s dictum to wear clean underwear. One human life in distress, one soul, one crisis; no problem, it’s what we do. It is the universe of one. It is the end of one. God help us when we can’t see the one.

*****

Early in my career I was called into the GYN room to deliver a 17-year-old girl who was miscarrying. The infant was fairly far along, probably 20 weeks. So it was fully formed and the sex was evident. It was a boy. There was no family there but one of the nurses held her hand and provided comfort as I maneuvered to handle the dead child. Following the delivery, the mother gestured that she wanted to see her child. I obliged her by placing the infant on her chest. She wept softly and called him by name. I was then called to another room for an immediate evaluation.

The nurse who had held the patient’s hand and given comfort and care entered my exam room and said: Our mother wants you to baptize the child. This is what she needed at this time. The child was beyond the realm of my skillset; the mother was not. Being a Catholic hospital, the priest on call – Father Bob of the God Squad – had been summoned, but it would be a while before he could arrive. Having heard that it would be some time before his arrival, the mother asked me to perform the baptism. Having been raised a cassock and cotta-wearing, High Episcopalian altar boy, I agreed.

She didn’t know me from Adam but she trusted me with this role. How she knew I would do it I will never understand. While she held the infant, I took the saline from the basin and said the words she desperately needed to hear. The scene was surreal. Techs were cleaning the room, mother crying, the nurse preparing to take the child as I poured water over the head: “I do baptize thee…” As I did it, a strange, cold feeling came over me and I had to fight back the tears.

Now I know what you’re going to say: This was a neurotransmitter problem. This was an autonomic nervous system dysfunction. This had nothing to do with any greater power. Maybe. You can have your view of it. Things moved quickly after that moment – as they always do – and I moved on to the next complaint. I can’t remember whether his was abdominal pain or a sprained ankle, but there was no time for reflection. In our business we move on.

Now, in comes Father Bob, who asks at the desk which room required a priest. The desk clerk told him that the doctor had baptized the baby. “Who was the doctor?” he said. A nurse chimed in: “Dr. Henry.” His eyes rolled and he shook his head a little. I’m afraid my reputation had preceded me. I might as well have been Lucifer himself. After visiting the mother and the deceased infant, the good Father sought me out: “You know this is kind of a union shop, don’t you, Greg?”

“I know.”

“You know, I’m supposed to bless you now, as if that’s supposed to forgive the life you’ve led and the sins you’ve committed.”

I said: “Yeah, I understand.”

As he blessed me and made the sign of the cross on my forehead, the strange, cold sensation came back for a few moments. “We need to step into a room,” I said with some urgency, as my tears started to flow. I couldn’t let anyone see this. We’re tough guys, wooden ships, iron men. Why me? Why this kind of emotion? He gave me a hug, said the mother loved the way that I handled her son and he reassured me I was now a better person for having done it. He also admitted that me being a better person wouldn’t take very much.

In a moment of weakness I said to him: “I’m not sure I should do this anymore.” His comeback stayed with me my entire career: “I’m not sure you should ever do anything else.” We never spoke of this again.

*****

So back to the ER, back to dealing with the societal problem which are the direct result of post-World War II unchecked freedom. All children are free; indeed have a right to get all the education they can, then move as far away as possible from their families. They have a right to come home each holiday season, find their mother or father in markedly diminished condition and rush them to the emergency department, assuming something dramatic must have happened to their loved one.

What’s happened is life. That’s right: life goes on whether you’re there or not. They were not there to assist and comfort their family. They were not there to learn eternal truths from their parents. Human relationships are characterized for the most part by lack of reciprocity. Someone is caring while not being cherished in return. Did these people think that if they left their family alone there’d be a federal program to provide love and respect and some degree with reverence to their parents?

Our adulation for things, for a new job, the big life, material things seems to have been our Faustian bargain for which we gave up the enjoyment of our elderly and the possibility of enjoying them just as they are. We are all hungry for such relationships. Life is like that for most of us. It’s the small unpleasantness rather than the great sudden tragedies which drag us down and make caring for our loved ones the quiet mellow-drama of the 21st century.

It’s not what we do but how we view it. We, like Linus, love the elderly as a concept more than we truly care for them as people – no, as an individual person. Before you descend into a headlong era of do-gooding by starting a senior emergency department, just remember that what people need is not a softer cot or wider aisles, but medical personnel – and indeed families – who actually gives a damn..

It is hard to be rejected, to be relegated to the margins and to accept that you have been given a life to live that seems limited, as if the time remaining will be wasted and thwarted at every turn. If we must thrust out our most recent ancestors into a bland mediocrity that is so characterized by “stuck living,” let’s at least do it with some recognition that such a fate waits for us all.

Pacem in terris

Photo by Austin Kleon

1 Comment

As always excellent…like my late used car salesman uncle would say “It’s all about who is doing what to who and who is paying for it”