A quick and easy life-saving solution, or an unjustifiable risk to patients?

As a resident, I was fortunate to regularly hear Scott Weingart speak at our Wednesday conference. So to me, bolus-dose vasopressors (or as Scott coined them, push-dose pressors) have just always been a useful thing to have nearby.

Say you have a crashing peri-intubation patient with a low MAP. Wouldn’t it be comforting to know that you can boost the blood pressure for your procedure quickly, albeit temporarily, while a drip is set up? We’ve had pre-filled syringes close at hand in our resuscitation bay for years, and push-dose pressors have bailed me out of at least a few tense situations. There are times when waiting for pressure-bagged fluids to exert an effect, or waiting for a drip to get set up isn’t in the patient’s best interest.

I just assumed that everyone else agreed. I didn’t realize that other specialties, and some of our own colleagues, would look upon EPs using push-dose pressors with suspicion – unnecessary at best, and too risky to recommend.

But that’s the perception that AJEM’s Letters to the Editor section gave this summer, with echoes across the EM social media world.

It began with the e-publication of a letter from two ED docs, Acquisto and Bodkin, in AJEM a few months back. In their letter, “Medication errors with push dose pressors in the emergency department and intensive care units” the authors advance the notion that FOAMed (Free Open Access Medication EDucation) has popularized push-dose pressors, and their patients are suffering as a result. They cite a few dosing errors at their hospital, like how phenylephrine “50” was ordered in a hypotensive ICU patient, but 50mg was given instead of 50 micrograms. They go on to argue that EPs and Intensivists are not “traditionally trained in medication manipulation” so mixing up phenylephrine or epinephrine is too risky, and there’s limited safety data on push-dose pressors to begin with. Instead of using these drugs as a bridge to vasopressor infusion or fluid resuscitation, the authors say we should just focus on pushing fluids and setting up a drip.

A thorough rebuttal appeared shortly after, from frequent EM #FOAMed contributors Nadia Awad, Howie Mell, Anand Swaminathan, and Brian Hayes (Awad and Hayes are EM Pharmacists; Hayes is also a clinical toxicologist). They made the point it’s not even clear these errors came after physicians had been listening to podcasts or reading blogs. Acquisto & Bodkin never reported a baseline error rate reported at their hospital, so it’s hard to tell if things are really getting worse. Plus, some of the errors reported aren’t even about push-dose pressors (an epi dosing error in anaphylaxis was one anecdote Acquisto & Bodkin cited, to buttress their case).

Awad et al, in their rebuttal, also make the point at push-dose pressors are described in both Tintinalli’s and Rosen’s EM textbooks. And not to put too fine a point on it, sources like EM:RAP, while popular for CME, aren’t free, and so can’t be considered FOAMed.

I’ve been practicing at the same urban academic ED where I trained, so I wasn’t sure if this was another case of ivory tower isolation. Maybe nurses in other EDs around the country can set up drips in a minute or two, obviating the need for push-dose pressors? Maybe I was imagining the benefits? Or Acquisto & Bodkin’s risk assessment was widely shared? I polled the EM Docs audience on Facebook, asking their impression of PDPs. It wasn’t even close:

The number of EPs saying PDPs were “reassuring but rare” was 143, and 129 said it was “lifesaving.” Only five people were in the “unnecessary” column and one called it “too risky” (people could vote for more than one answer).

I also heard some great anecdotes (see below).

Weingart also revisited this topic in an August Emcrit podcast (#205), the first explicit update to his push-dose pressors edition from 2009. He clarified that, instead of focusing on short-lived hypotension (a rarer entity than we used to think) it may be best to conceive of PDPs as the means to improve critically low perfusion – a bridge to a likely pressor drip.

He also explained that he now prefers push-dose epinephrine to phenylephrine for most situations, citing epi’s inotropy as well as its pressor response. To him, the best indication for phenylephrine, a pure alpha agonist, is hypotension in the setting of rapid AF and other tachycardias.

I’m still glad we have pre-filled 100 mcg/mL phenylephrine syringes close at hand, in my ED. I can push a milliliter or two over the course of several minutes, as a drip is set up. If I had to make it, I’d take 1 mL of 10mg/mL phenylephrine and mix it in a bag of 100mL NS; then I’d draw some of that into a syringe to end up with the same 100 mcg/mL solution.

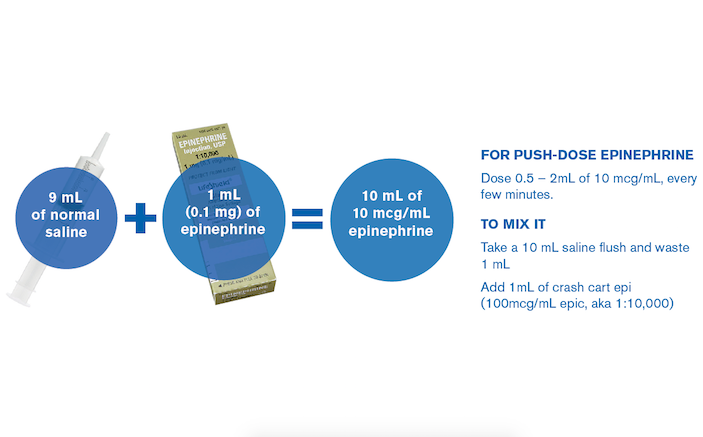

For push-dose epinephrine, dose 0.5 – 2mL of 10 mcg/mL, every few minutes. To mix it, take a syringe with 9mL of normal saline, and add 1mL of the “cardiac” epinephrine (an amp of cardiac epinephrine has a concentration of 100mcg/mL – also is known by its 1:10,000 formulation). Weingart’s website has labels (along with instructions) to affix to the syringes, to further minimize risk.

Reviewing the correspondence in AJEM’s Letters page, and the thoughtful response from Weingart and others in the #FOAMed community, I’m reminded of the now-clichéd debate over FOAMed vs traditional materials and peer reviewed press. Of course, there are criticisms to be made of FOAMed (I’ve made several, in these pages). But this is one case where the FOAMed has outshined peer review. FOAMed practitioners have done a solid job introducing a new therapy to EPs, including a number of caveats and tips for safe handling. If you care for sick patients in an ED like mine, I can’t see how you wouldn’t want push-dose pressors in your armamentarium. And if I stuck with traditional media and peer reviewed literature, I would have a lot more doubts about safely and responsibly using this potentially life-saving therapy.

Case Study: Push-Dose Pressors in Real Life

I had an 80-year-old patient from an adult family home, BIBEMS in respiratory distress, hypoxic at 86% sat, BP 65/55 on arrival. He also was obese with rock hard abdominal distention that I suspected impaired venous return/pulmonary reserve. I knew he would tank on induction. We have ED pharmacists, who carry a go-bag with everything we need, including PDPs. I needed to intubate, but decided to resuscitate first.

Patient was sitting bolt upright, on NRB and holding sats in 90s. Not a bipap candidate due to hypotension. I started peripheral NE, titrating up while I placed femoral line. During the line I ordered vasopressin (which has to be sent up from pharmacy). Patient really had to be upright to breathe, so I had the RN drop head briefly for the dive under the inguinal, then back to upright. I also gave NS bolus, but patient was not fluid responsive.

We got the BP to 90s and sat to 94% before taking the airway. It felt like the best I was going to get and was running out of pulmonary effort. He was on norepinephrine at about 30mL/hr at this point. Vasopressin hadn’t arrived yet.

We used ketamine 100mg and 95mg rocuronium for induction. Placed in ear to sternal notch, about 45 degree HOB elevation, used continuous NC oxygen. Very fast intubation with McGrath video laryngoscope and put on vent, HOB moved to about 20 degrees for RT to manage tubing and I moved to the side of bed and reassessed.

I didn’t get the bump out of ketamine I hoped for. He tanked anyway to an undetectable femoral BP, but good HR, good on vent and faint carotid.

Phenylephrine had already been drawn up and ready by pharmacist, so immediately gave first phenylephrine 100 mcg push. Still no BP so repeated second phenylephrine. Vasopressin arrived, RN starts to hang and gave 3rd phenylephrine push, now with a BP 57/46, then 88/62 before and 91/67 mmHg after vasopressin. Levophed was up to 37.5 mL/hr when vasopressin added.

PDP bridged me, saved the day, and I got him stable to the point of BP 135/71 about 30 minutes after he got phenylephrine. The admitting intensivist walked in and asked, ‘why did he need intubation? He seems stable’. Felt like a win. Back to baseline on discharge.

-Dr. Susan Derry

1 Comment

Thank you, Thank you, Thank you. I’ve been pushing phenylephrine for years as a bolus to buy time, until my pharmacy frowned on this as this was outside their normal spectrum of care, and I had to get approval to keep doing this. My case involved a 17 year appendectomy that during induction, the trochar went thru the iliac artery. The hospital that I worked at called a code, and I as the ED doctor responded to a situation where the heart rate was 160’s and blood pressure 40’s. Turning off the anesthetics was done by the cRNA, but only one IV was established. Knowing that acidosis was just around the corner, followed by vasodilation from the acidosis, and further lowering of the blood pressure. Rather than wasting the time to place a central line, or calling for levophed, it was simple, less than 20 seconds, to take 0.1 ml and dilute to 25 ml, to make 40 mcg/ml and get the pressure up until better iv access and blood arrived.