To read the original case: Click here

THE RULING

The plaintiff alleged that the PA was negligent for failing to consult his supervising attending or an orthopedist before ruling out such a serious diagnosis. The plaintiff alleged that after reviewing and signing off on the PA’s note, the attending physician should have recognized the patient had multiple symptoms consistent with compartment syndrome and should have called the patient back for further evaluation. The defense argued that the patient’s symptoms were nonspecific in nature, that nontraumatic compartment syndrome in an otherwise healthy patient is rare, and that with the patient’s history of recent physical activity, an initial diagnosis of a muscle strain was reasonable. In addition, the defense alleged that the injuries the patient sustained were caused by his refusal to return to the emergency department when his symptoms worsened through the night. The jury believed both the defense and the plaintiff’s arguments. Their total verdict was $7 million dollars, with 20% attributed to the actions of the physician assistant and 40% attributed to the actions of the supervising attending physician. The relatively higher award against the attending physician resulted from medical testimony, hospital protocols, and statutory language demonstrating that when a PA treats a patient, the supervising attending physician is still ultimately responsible for the patient’s care. The jury also reduced the plaintiff’s award by 40% for the patient’s comparative negligence in refusing to return to the emergency department sooner when his pain worsened.

ANALYSIS

Just because it has Hair doesn’t make it a Shih Tzu

Just because it has Hair doesn’t make it a Shih Tzu

By William Sullivan, DO, JD

Acute nontraumatic compartment syndrome is considered a rare diagnosis. Compartment syndrome is often – but not always – a result of a traumatic injury. Several sources note that compartment syndrome occurs in between 1% and 10% of lower leg fractures. Other causes of compartment syndrome include external compressive forces, postoperative complications, burns, vasculitis, DVT, seizures, and infections. Nontraumatic exertional compartment syndrome is largely relegated to case reports within the medical literature. A diagnosis of compartment syndrome begins with a clinical suspicion. Recall the “7 Ps” of compartment syndrome: Pain, Pressure, Paralysis, Pallor, Pulselessness, Paresthesias, Poikilothermia. However, also be aware that some of these symptoms are late manifestations of compartment syndrome. By the time a patient has developed pulselessness, paralysis, or pallor, it is likely that significant damage to the underlying tissues has already occurred. Confirmatory testing involves use of an intra-compartmental pressure monitoring device such as a Stryker needle. Compartment pressures more 30 mm Hg are considered abnormal and warrant orthopedic evaluation. Once compartment syndrome has been diagnosed, urgent fasciotomy is necessary. Fasciotomy within 6 hours of symptom onset usually results in complete recovery. Delaying fasciotomy longer than 12 hours after symptom onset significantly increases the likelihood of permanent muscle and nerve damage.

In this case, there jury had to decide two issues: misdiagnosis and supervision.

The patient’s presenting complaints included pain and swelling of the lower leg. While there was no bony point tenderness or erythema, there was also no documentation of the patient’s distal circulatory, sensory, motor, and neurologic exams. Although the physician assistant’s note stated that the patient had no evidence of compartment syndrome, both pain and swelling are evidence of compartment syndrome. Although these are nonspecific findings, a notation that there was no evidence of compartment syndrome when evidence of compartment syndrome did exist made it more difficult to defend the misdiagnosis. Based on the examination documented, a diagnosis of muscle strain or shin splints certainly seems like a reasonable diagnosis. However, if sensory, motor and circulatory systems were normal on exam, notation of the normal exams and better documentation of a description of the swollen area in the patient’s leg may have made it easier to allege that the patient’s symptoms didn’t warrant immediate fasciotomy and that outpatient follow up was appropriate.

Unfortunately, as with so many other malpractice cases, the jury was persuaded that because the patient’s rare diagnosis had common physical findings, clinicians should rule out the rare diagnosis any time those clinical findings are present. The logic is equivalent to saying that all Shih Tzus have hair, therefore any animal that has hair should be considered a Shih Tzu until definitive testing proves otherwise. Imagine the tremendous increase in costs of medical care and in patient morbidity if every patient presenting with symptoms of a muscle strain had to be tested for compartment syndrome. While Brady argues that unclear findings or potentially worrisome symptoms may require additional testing or consultation, most clinical cases simply aren’t that straightforward. A normal presentation to one provider may be worrisome to another provider with either more or less experience. It also seems as if sympathy may have played a part in the jury’s determination that the PA was negligent for misdiagnosing compartment syndrome: The patient entered the emergency department after running about on a soccer field and was eventually wheelchair-bound after misdiagnosis of this uncommon condition. With regard to the patient’s medical care, then, the care appears reasonable, but better documentation would likely have made the case easier to defend.

The larger portion of the jury verdict went against the emergency physician – which seems illogical because the physician never evaluated the patient. In many states, supervising physicians are fully responsible for the actions of the PAs and NPs they supervise. For example, statutory language in the Illinois Physician Assistant Practice Act states that the supervising physician “maintains the final responsibility for the care of the patient and the performance of the physician assistant.” Hospital policies and employment contracts also create duties to supervise (and therefore accept responsibility for the actions of) physician extenders. Sample language from the contract of a national emergency medicine contract management group requires all physicians signing the agreement to “supervise any physician extenders as may be requested by the Partnership” and another large emergency medicine contract management group requires physicians to “adhere to any applicable practice guidelines regarding the supervision and utilization of assigned advanced practitioners.” In this case, statutory language and hospital policies created a duty to supervise the physician assistant and also imposed liability on the supervising physician for the actions of the physician assistant. The jury decided that the physician had not properly supervised the care of the physician assistant and had not properly addressed the PA’s documentation of potentially concerning physical findings. When reviewing a chart reflecting a patient complaining of post-exertional pain and mild swelling to the mid-shin which is worse with walking, it is certainly reasonable to conclude that the patient was suffering from a muscle strain which would not require that the patient be called back to the hospital for further testing. However, just as with the PA’s misdiagnosis, the jurors were persuaded that the supervising physician’s review of the chart had missed telltale symptoms of a rare disease. Although the supervising physician’s actions in this case also seemed reasonable, the large verdict against the physician highlights that the duties in supervising physician extenders involve more than simply signing a pile of charts at the end of a shift.

One additional point regarding this case. The jury reduced the plaintiff’s award by 40% for comparative negligence. Patients may be held responsible for their injuries if they act negligently. For example, failing to take prescribed medications, failing to keep follow up appointments and failing to follow discharge instructions (such as to return if symptoms worsen) may all be considered as negligent acts by the plaintiff. A jury may then consider such negligent actions when deciding whether a plaintiff should recover any award in a malpractice suit, and if so, whether that award should be reduced. A patient’s comparative negligence is considered an “affirmative defense” to a lawsuit, meaning that even if a patient clearly had some fault in causing their own injury, that fault doesn’t prevent the plaintiff from fil-ing a lawsuit. Instead, the plaintiff’s negligence may reduce a defendant physician’s liability or, in some cases, may absolve the physician from liability altogether. Most states have laws barring a plaintiff from recovering any damages if the plaintiff contributed more than 50% to his injuries. A minority of states allow a plaintiff to recover a percentage of the damages even if the plaintiff was 99% liable for his injuries. In this case, the jury reduced the plaintiff’s award by nearly $3 million by deciding that his negligence was responsible for 40% of the injuries he incurred.

Beware benign explanations for dangerous conditions

Beware benign explanations for dangerous conditions

By Brady Pregerson, MD

Like most medical malpractice cases that make it all the way to trial, this one has some valid arguments on both sides. It is a valid point from the defense that exertional compartment syndrome is an extremely rare condition and that shin splints are quite common. It is also true however, that it would be unusual for a patient with shin splints to decide to come to the emergency department, and that unilateral pain and visible swelling would not be expected from shin splints.

Every malpractice case has a lesson to teach, and the main one here is that to distinguish a serious diagnosis from a more common benign condition which it may mimic, requires active surveillance and suspicious mind. It is important to keep in mind that although some patients use the ED as a substitute for primary care, most patients who visit us are there because their symptoms are unusual or concerning to them and they are worried they may have something serious. This is why the incidence of serious conditions like MI or appendicitis are more common in ED patients than patients presenting to a doctor’s office. Although they may be worried, many ED patients think, or at least hope, that their symptoms are actually due to something benign. Be cautious when a patient offers you, their provider, a benign explanation for their symptoms. For example, the patient with an MI may tell you their pain feels like indigestion or their GERD. The patient with appendicitis may tell you they ate something bad and probably have food poisoning. The patient with a leaking AAA may tell you he lifted something heavy and must have strained his back. And, the patient with exertional compartment syndrome may tell you the pain feels like shin splints. There is often a benign, but incorrect, explanation for a dangerous condition. The cautious provider won’t let that explanation derail them from following the first rule of emergency medicine: consider the worst diagnosis first. If everything fits a benign condition, it is more than reasonable to make that diagnosis. However, if something doesn’t quite fit or is potentially worrisome, diagnostic investigation should usually occur.

If the provider in this case was able to document that the pain was identical to prior times this patient had had shin splints and that he only came to the ED because he wanted a prescription and couldn’t reach his doctor and also document a normal exam, then no investigation would have been warranted. However, that was not the case here. We don’t know if this patient had had this type of pain before, and moreover, unilateral pain and swelling were noted. In the medical decision making part of the chart compartment syndrome was even considered but then deemed unlikely, and therefore not ruled out. In retrospect, it was an error to stop there without either consultation or definitive testing, but was it malpractice? Do all patients with unilateral leg pain require a work-up for compartment syndrome? The answer is: obviously not.

Did this patient? From the charting it isn’t completely clear.

The second important lesson in this case is to pursue testing and/or consultation when the clinical presentation is unclear. When everything fits and the treatment is not controversial, consultation may not be necessary. However, the more parts of the clinical presentation and diagnostic testing that don’t fit, the more likely that a consultant is likely to be helpful. For a PA, consultation may mean no more than involving their supervising physician while the patient is still in the ED. For an emergency physician, this may mean consulting a specialist, before or after diagnostic testing. It’s never a bad idea to get a second opinion when the presentation is atypical, and it is always wiser to do this while the patient is still in the ED rather than to have it occur for the first time in follow-up. You never want your patient to be asked, “They did WHAT in the emergency department yesterday?” If a joint plan between the treating provider and consultant is made and documented, a patient is more likely to feel that care has been appropriate, even if there is an unfortunate bad outcome. It is an unfortunate but not infrequent occurrence that a provider that makes a diagnosis on a second or subsequent visit, will criticize, either directly or indirectly, the care provided by the earlier clinician. This criticism can become the seed for a lawsuit that would have not otherwise occurred. This too may be prevented by consulting while the patient is still in the ED. Side note: please remember, when you are that second provider not to “throw your colleague under the bus”. Instead, if possible, try to offer an explanation why the care provided the day prior was actually appropriate given what was known at that time. If you feel you need to say something at least attempt to speak to the prior provider first so they can tell you the information available to them at that time. Also be aware that if you badmouth another provide and trigger a lawsuit, you may be called into court to testify as a treating provider.

In summary, my opinion is that in this case, although it did not represent ideal care, it was reasonable to make the diagnosis of muscle strain with instructions to return if worse given that exertional compartment syndrome is so rare and shin splints so common. Unfortunately, the jury decided otherwise. The main clinical lessons from this case are to 1) always evaluate for potentially serious explanations of a patient’s symptoms unless all the available information is a perfect or near-perfect fit for the benign condition and 2) obtain appropriate diagnostic testing and/or consultation when a serious condition is a distinct possibility.

5 Comments

$7,000,000

Let that sink in.

20% to the PA, or $1,400,000, or 14 YEARS or work at $100,000/yr

40% to the Physician, or $2,800,000, or 9 YEARS of work at $300,000/yr

Because of a charting error. Or a clinical error. Or the patient’s failure to return to the ED. Or bad luck.

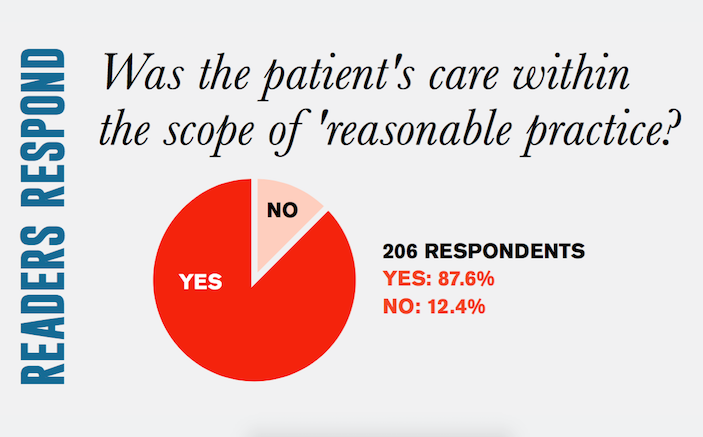

As somebody who’s currently going through a lawsuit which I’m certain 87%+ of physicians would agree with my care, this type of story terrifies me.

Brady, you’re right that we can learn from every bad outcome, QA review, or malpractice case. With that said, how many of us think this is the case to change our practice?

How many of us have seen a case of exertional compartment syndrome (I have not ever)? Severe enough to require fasciotomy? And severe enough that if a fasciotomy is not done (of the calf!), to then cause Complex Regional Pain Syndrome that spreads to the back and causes lumbar neuropathy severe enough to require wheelchair use, continuous disability, and “constant care”?

While every case is a lesson, perhaps this is not the case to stand on based on the summary provided.

Again, to summarize, a soccer player presented with calf pain that had progressed since he played soccer approximately 24 hours earlier. There was pain and minor leg swelling. You may think there should have been more documentation to protect yourself against a unicorn event like “exertional compartment syndrome”. But what would that documentation have been? Is there any assertion that any of the classic symptoms of compartment syndrome were present, could have been detected, but were ignored by the PA?

I’ll leave you with a challenge since you suggest speciality consultation– provide a script you think we could use when calling the Orthopedist on call, to convince them that they needed to (fill in the blank, depending on what you believe) — Come see this patient and measure their compartment pressure? Encourage us to stick a Stryker into all four calf compartments and measure their pressures? Talk us through an emergent fasciotomy over the phone with the information provided? Keep in mind the patient apparently had deteriorated beyond salvage when he saw the Orthopedist the next day (so that is not an option to avoid a $7M judgment).

I vote for “ridiculous”.

This case is a zebra In the jungle of squirrels and dogs in a metropolitan city like Chicago where I live and practice. With ER clinical experience 100% in the pit over 20 years practice in multiple city and suburban ED’s, I have nor have I heard of any such a presentation of compartment syndrome from my experience or from my colleagues. It’s a shame that we have to now perform compartment pressures on shin splints, or that what it sounds and looks like to me. Either this exam of the leg was grossly underestimated of the swelling and pain, or this is one case in a million and it happened to be on your unlucky shift. I don’t think one in a million case should be rewarded as a standard of care, it’s not what a routine or a similar ER physician or PA/ NP would have done with that similar presentation at that time. It’s ridiculous that the jury or even the case to make it to court. That’s why when that headache or diarrhea patient comes in and goes home with a benign diagnosis, get the bill for multiple thousands of dollars due to CT scan and excessive CYA testing. You do what you think is right, documents it, ” no sign of compartment syndromes” , and suffer the consequences.

P. M.

Could you please provide the actual citation for this case?

Thank you.

RM

This case (at least as presented) is frankly infuriating. The care was obviously reasonable. The one part of it I wouldn’t defend is that a neurovascular exam was not documented (though I suspect it was done, this doesn’t count). I agree you simply have to document your specific NV findings in cases like this. Simply saying “no evidence of compartment syndrome” isn’t enough. Document the findings and reference them in MDM saying “based on these findings there is no clinical suspicion for ACS, d/w pt this most likely is a benign and self limited condition and further invasive testing more risk than benefit, however very important to return if worsening and to f/u with ortho if symptoms persist”

All that being said, I would simply love ANYONE to explain to me what more could actually have been done in this case. If I call ortho with this story I’m getting a nasty response and a click on the other end. There is absolutely no way ortho agrees to come consult this case in person.