When it comes to mass casualty planning, it’s not a game—it’s a philosophy.

When a mass casualty incident occurs, emergency physicians are quickly thrust onto the front lines. That is precisely what happened on October 1st at Sunrise Emergency Department in Las Vegas the night Stephen Paddock opened fire on a music concert, killing 58 people and injuring more than 500. This article, the first in a series on mass casualty incident (MCI) strategies, takes lessons learned from that event in order to highlight tough questions that your institution will need to answer to be prepared for the worst case scenario.

THREE CURRENT MCI STRATEGIES

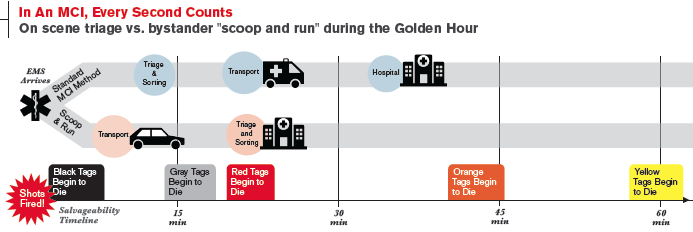

Methods for handling MCIs are based on the military model, which takes into account the typical long distances from the hospital that the military operates from. These long distances would burn precious minutes from the Golden Hour. To bridge these distances and extend the Golden Hour, the military relies on initial Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) and uses smaller forward Operating Rooms, physician transport, pre-hospital transfusions, and other methods to stabilize patients prior to them coming to the main hospital.

These methods prolong the Golden Hour for extremity trauma. But only early surgical intervention will save penetrating torso trauma with blood loss. In most metropolitan areas in the United States, there is one if not multiple trauma centers accessible within minutes. There are no long distance issues, and many of the above methods that the military uses for prolonging the Golden Hour are not used in civilian prehospital care because of the close proximity.

Second, the SALT/START methods for triage in MCIs developed to sort the patients, prevent overwhelming hospitals with them, and prevent exhausting the hospital’s resources. The idea is to evenly disperse the most critical Red Tag patients first, then continue to stabilize and distribute the patients from the scene to the hospitals. These methods keep the Black and Gray Tags in place and allow the Gray Tags to die on scene to help prevent overwhelming the hospitals and exhausting resources.

A third method of handling prehospital care in a MCI was developed on the streets of the inner city where medical training is at a minimum. In this method, friends or bystanders bring the victim with no prehospital care and drop them off in the ambulance bay of the ER, the proverbial Homie Drop-off. Because of the lack of medical training, any victim automatically overwhelms the available resources, constituting an MCI. Legend has it that one inner city had become so dangerous that no one wanted to work EMS.

Biker gangs were employed to transport gunshot victims. With minimal medical training, they would grab the gunshot victim, throw them in the ambulance and drive to the hospital as fast as possible. Scoop and run. Since no time was spent on scene, they were brought to the ER very early in the Golden Hour.

PREPLAN FOR THE WORST CASE SCENARIO. EVERYTHING ELSE WILL BE EASIER

In a large scale U.S. urban penetrating trauma incident, the military method would not be used since trauma centers are so close. Instead, rescuers would use the second method: Patients would be tagged, stabilized, sorted on scene, then distributed to hospitals in an attempt to save the most number of victims possible. Black and Gray Tags would be passed over to allow for Red Tags to be prioritized for hospital transport, in order to obtain the maximal possible save rate.

There were two issues I had with this method during the Las Vegas shooting in October. The first was that potentially viable Gray tag patients would be allowed to succumb to their injuries on scene. Letting these patients go never sat well with me. Secondly, the time spent on scene sorting and stabilizing these patients was time deducted from the Golden Hour. This sorting time was also the very small window in which a Gray Tag could be resuscitated.

Now, what if the third method was employed? What if prior to EMS setting up a Casualty Collection Point, bystanders employed the “Homie Drop-off” method? In the worst case scenario, where the majority of the patients were brought in by the “Homie Drop-off” method, you’d face a large bolus of patients in minimal time with no prior sorting. The massive number of victims would overwhelm the hospital staff. On the other hand, Grey Tags would have a chance at resuscitation, and time lost in the Golden Hour would be minimal.

THE REALITIES OF HOMIE DROP-OFF: ASK THE HARD QUESTIONS

What if there was an MCI and the bystanders did not wait for EMS and instead employed the “Homie Drop-off” method of triage and transport? How could this be handled? The public is not trained in the military or EMS methods of triage and prehospital care. It is not a far-fetched idea that bystanders would transport patients prior to EMS arrival.

October 1st was an example of this approach to pre-hospital care. A majority of the critically injured patients arrived at the hospital even before a casualty collection point could be established on scene. The idea of a massive bolus of patients by this method was a possible scenario with a small probability. However, adjusting to handle this tidal wave of patients raised many questions.

1. With so few doctors there during Phase 1, how could you treat all of them?

The analogy is found in fine dining. Chefs deal with similar situations daily during the dinner rush. There are numerous orders and only a few sous chefs. If the chef just stared at the roast with hours of cook time, the short cooking time medium rare filet mignon would burn on the pan. Chefs cook multiple meat dishes simultaneously by knowing the cook times of each piece of meat. These timing issues are similar in these two different fields. However, the difference is that pieces of meat are packaged and already identified for the chef. By triaging correctly, we identify the patients. Then timing is as simple as attending to the Gray/Red Tags first, while the Green Tags wait.

2. With overwhelmed staff due to the massive influx of patients, how do you get doctor and nursing tasks done?

Involve all available staff to do non-nursing/non-doctor tasks, such as transporting, or placing I.V.s. In our case, the Golden Hour was managed by the staff on hand. The staff that was called in had to respond to the initial notification and fight traffic and road blocks just to make it to the ER. Using your available resources wisely is the key to surviving the onslaught of the Golden Hour.

3. How could you organize this massive influx?

Place patients in physical zones according their color code: Red Tags in the resuscitation bay, Orange Tags adjacent to the resuscitation bay, Yellow Tags next to the Orange Tags, and Green Tags in the largest area.

4. How could you triage this massive influx quickly and correctly?

Get trained in the art of Applied Ballistics and Wound Estimation in order to better understand how gunshot wounds injure and kill.

5. Would the standard red, yellow, and green tagging system triage handle a massive number?

No. Filling out tags is precious time lost from the Golden Hour.

6. How do you monitor hundreds of victims?

Use the “Overwatch Method,” where nurses watch over patients from a central location. Monitor for apnea and decreased mental status. Palpate for carotid pulses.

7. How do you find the needles in the haystack?

The needles in the haystack will declare themselves by loss of mental status, apnea, or thready carotid pulses. Accurate triaging will organize them so that they decompensate in an orderly fashion.

8. Can trauma surgery complete the ABC’s of ATLS and do surgery?

No. ER will need to manage the ABC’s, and surgery would perform the secondary survey and prioritize for the OR.

9. What do you do when you run out of supplies?

Use the supplies you have, then improvise when you run out while you wait for restocking from central supply.

10. How do you handle security?

Due to the nature of the initial attack in Las Vegas, there was the strong possibility of a secondary attack on the hospitals, so security was of the utmost importance. Heavy police and security presence in the ambulance bay kept family, bystanders, and Good Samaritans from interfering.

Many of the Good Samaritans and bystanders were intoxicated, and credentials could not be identified. It would only take one person with bad intentions to cause havoc if they had infiltrated into the patient care area.

CLINICAL CARE BASICS

Airway: How can you quickly intubate so many patients?

Bring them around you in a flower pattern and have Etomidate and Succinylcholine distributed amongst the staff.

Breathing: How can you ventilate so many patients?

According to Newman et al., a single ventilator can be used for multiple patients in a disaster surge.

How will you monitor all the ventilated patients?

The few vented patients should be on a monitor.

Is there enough time to do a needle thoracostmy then place a chest tube tube in the patient?

Why do a needle thoracostomy if you are going to follow up with a chest tube right after? Just be efficient and perform the definitive procedure.

Can you do a chest X-ray on everyone?

No. Use your stethoscope and clinical skills.

Circulation: Is there enough time to place a central or intraosseous line on everyone?

Place bilateral 14 – 18 gauge IVs on all Orange and Yellow Tag patients before they crash. Use IO and central lines on Grey and Red Tags who are already crashing.

How can you rapidly transfuse so many people?

Get the blood out of the blood bank and have it staged ready to go.

What do you do with all the tourniquets that were placed on the patients in the field in triage?

Did the gunshot go through the anatomical window of the artery? Palpate the distal artery as you take down the tourniquet. If it doesn’t bleed and the pulse is intact, the bullet missed the artery. Leave the tourniquet loose and in place just in case you were wrong, and the artery was spasming. If it rebleeds, simply tightening the tourniquet will again control the bleeding. You don’t want to lose a limb while you’re busy resuscitating the most critical patients.

ONE ALLOWABLE CHOKE POINT

During triage in the driveway, we knew that traffic up the ambulance driveway would lead to panic by those driving, and the passengers would then bail-out of the vehicle and swarm the triage area. This would rapidly lead to the breakdown of the organization that had already been achieved.

Setting up the triage area like a NASCAR pit crew allowed us to pull patients out of cars rapidly. Then, quick visual assessment of the bullet holes and trajectory allowed Applied Ballistics and Wound Estimation in seconds. This was the only choke point that was allowed to remain. This artificial choke point allowed us to have a controlled flow of patients through triage while sorting out non-injured family members, bystanders, and Good Samaritans. Knowing that panic would cause the horde to stampede, having one highly controlled entry point kept the horde at bay. Police and security facilitated the movement of the most stubborn and discouraged others from trying.

LESSONS LEARNED

In November’s initial article on the Las Vegas MCI, we covered the work-arounds that kept the patients flowing efficiently through the care process. Initially, the aim is to establish the flow and obtain complete control over patient movement. Police and security kept the order and allowed medicine to be performed without the interference of unruly family or bystanders.

During our triage in Las Vegas, the expectation was that triage into the Red/Orange/Yellow zones would be 90% correct. But the potential loss of 10% of the victims due to inaccurate triage did not sit well with me. This was easily solved by the fact that our nursing staff is attuned to visually identifying crashing patients and bringing this to the attention of the ER physician.

This caught 99% of the patients, but I knew that there was still the potential for misplaced patients or misidentified injuries. There were two Red Tag patients that had been misplaced into the Green Zone, but these two patients were found early by Dr. Walker and I when we were circling the ER looking for crashing patients.

In an effort to make patients more comfortable, patients were moved to other locations by others coming in during Phase 2. Patients evaluated during Phase 1 with concerning injuries were moved to other locations, including back out to the ambulance bay. With the potential for a secondary attack, the ambulance bay provided no cover for incoming bullets. These patients were moved back indoors, and patients that were moved to secondary locations were assigned to the incoming doctors. There is the old adage that states, “Too many cooks spoil the broth.”

Unless critical issues arise from the initial plan, don’t deviate from the plan. Good Samaritans can be a potential hazard in this situation. It is human nature to want to help in a catastrophic situation, but unvetted help can be a security risk. Some of the Good Samaritans were intoxicated, and off-duty paramedics pulled patients from cars and triaged them incorrectly.

There were some nursing students that attempted to pose as nurses, requesting to help. Adequate security and a watchful eye prevented anything catastrophic from occurring. Just prior to Phase 1, a flight crew had brought in a patient, and an EMS crew brought in a severe head injury. The flight crew paramedics and nurse that stayed were instrumental in bolstering our numbers early, before any call-in staff could arrive. I found out later that many of the EMS crews returned to the scene only to sit and wait.

If the EMS crews had dropped of their initial patients and assisted in the ER before returning to the scene, they would be trained and vetted help that could assist the staff in the hospital. Aim for small victories. The small victories give you and the staff confidence that things are moving in the right direction and pave the way for medium and larger victories.

Positive resuscitations resulted from sorting out the initial Gray/Red Tags from the crowd of patients. The positivity fosters a relaxed state of thought in which improvisation to unexpected problems springs forth. When I entered Station 1 for the first time and saw that only resuscitations were occurring there as planned, I experienced my first small victory. I was then able to come up with the idea of co-locating all of the neurosurgical trauma to the trauma ICU to free up our Phase 1 team from continuing the maintenance work while multiple resuscitations were still occurring.

This also brought about the idea for distributing Etomidate and Succinylcholine to the staff, followed by the idea of pulling all of the blood out of the blood bank. After all, how do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

2 Comments

Very interesting article but the notion of having biker gangs throw gunshot wounded victims in an ambulance and racing to an ED strikes me as incredulous. Not only is the notion of a biker gang member driving an ambulance – presumably without any emergency driving experience – nocent, but one has to wonder where he got the ambulance in the first place! Maybe I missed something, he was “employed” to do this? He had contact with Medical Control, he knew how to operate the radio? He didn’t drive like an adrenaline-crazed junkie, running red lights and hopping onto the sidewalks? Who assumes liability in a case such as this?

At least there was minimal time was spent on the scene.

It does say, “Legend has it…”