Almost half of patients today fail to receive guideline-directed care, and there is evidence to suggest an inverse relationship between clinical experience and quality of healthcare. Specifically, “physicians who have been in practice longer may be at risk for providing lower-quality care.”(1) This is due in part to the fact that physicians, who are the quintessential filters of medical reporting and new innovations, do not wish to be the first or the last to adopt a new strategy.

Almost half of patients today fail to receive guideline-directed care, and there is evidence to suggest an inverse relationship between clinical experience and quality of healthcare. Specifically, “physicians who have been in practice longer may be at risk for providing lower-quality care.”(1) This is due in part to the fact that physicians, who are the quintessential filters of medical reporting and new innovations, do not wish to be the first or the last to adopt a new strategy. To this end, physicians need to develop a healthy skepticism to most effectively walk the line between premature adopter and laggard. Fortunately, secondary peer-reviewed literature (e.g. ACP Journal Club, Annals EM Evidence Based Emergency Medicine, Journal of Emergency Medicine EBM section) is increasingly prevalent, yet keeping current with the latest EM advances is still challenging. Each month, physicians are inundated with news of pharmaceutical ghost-writers compromising scientific reporting, promising new innovations rushed to market only to reveal significant side-effects in post-marketing analysis (nesiritide, rofecoxib), and sponsored opinion leaders with undisclosed conflicts of interest. Additionally, industry representatives learn social behavior techniques to identify and promote opinion leaders to modify clinician’s perspectives and practice in favor of their product (Moynihan 2008, Fugh-Berman 2007). Against this background of confusion and competing influences, what, who, and when should the thoughtful clinician believe?

Clinical research in general is a messy business. In comparison, consider the bench researcher who can control the universe of an experiment including the substrate, temperature, and quantity of an exposure. On the other hand, in the emergency department, I’m ecstatic if I can simply chart uninterrupted on my patient in the EMR before the system crashes and I have to reboot. I don’t even pretend to be able to control extraneous variables like an accurate history, let alone reliable compliance or follow-up. Within this chaotic setting, clinical researchers endeavor to collect data, randomize subjects for an intervention, and then track outcomes over some period of time. Obviously, our research findings will be inaccurate to some degree because of chance alone (random error) which will tend to become obsolete as more measurements are obtained (because in general the random error is equally distributed above and below the true value). Bias, however, is not related to chance and will not be eradicated by simply recruiting more subjects to measure. Bias can occur as measurement instruments are selected, when patients are selected, during the measurement process, in obtaining outcomes data, during the data analysis phase, or in the interpretation and reporting of research findings. One EBM leader once cataloged 35 distinct forms of bias for readers and researchers to contemplate. There are probably many more forms of bias.(2)

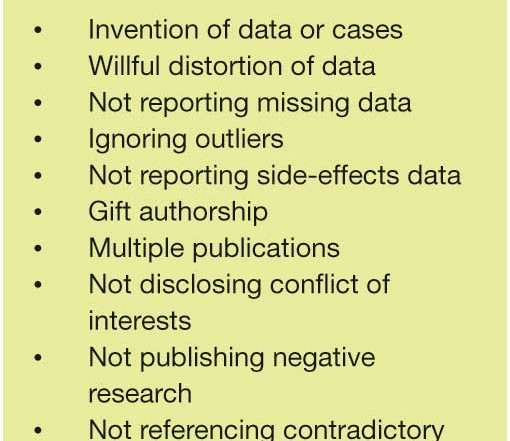

Bias and random error are usually not intentional, but recent developments mandate that physicians rapidly develop an enhanced understanding of how deliberate misrepresentation and blatant deception can and do occur in the medical literature. Additionally, the pharmaceutical industry is not the sole proprietor of misinformation. CME events, organized medicine, guideline committees – even professional publications like this one – can mislead clinicians with incomplete or inaccurate interpretations of the medical literature. In fact, instruments to measure bias in CME have been developed (Takhar 2007). However, industry is the best-recognized culprit. For a moment, put yourself in the suede shoes of Acme Biomed Company’s CEO as you contemplate how to maximize profits for your shareholders (thereby ensuring your own job security). What if the development expenses for Agent X or Medical Device Y has cost your company a sizeable chunk of capital, but has been found to possess dangerous side effects or limited applicability? If your data alone is not compelling or comes complete with red flags for healthcare consumers, you would likely brainstorm to develop a list similar to Table 1 (3).

Bias and random error are usually not intentional, but recent developments mandate that physicians rapidly develop an enhanced understanding of how deliberate misrepresentation and blatant deception can and do occur in the medical literature. Additionally, the pharmaceutical industry is not the sole proprietor of misinformation. CME events, organized medicine, guideline committees – even professional publications like this one – can mislead clinicians with incomplete or inaccurate interpretations of the medical literature. In fact, instruments to measure bias in CME have been developed (Takhar 2007). However, industry is the best-recognized culprit. For a moment, put yourself in the suede shoes of Acme Biomed Company’s CEO as you contemplate how to maximize profits for your shareholders (thereby ensuring your own job security). What if the development expenses for Agent X or Medical Device Y has cost your company a sizeable chunk of capital, but has been found to possess dangerous side effects or limited applicability? If your data alone is not compelling or comes complete with red flags for healthcare consumers, you would likely brainstorm to develop a list similar to Table 1 (3).

Unfortunately, pharma would have little success in convincing us to change our practice if it weren’t for our colleagues who work on behalf of pharma. While pharma support and endorsement is not in itself wrong, failing to fully declare one’s relationship with pharma is misleading and potentially harmful. Professional journals have been the traditional vehicle to disseminate new findings to a large audience. Since 14% of submissions include undisclosed financial conflicts, journal editors have recently mandated increasingly transparent author conflict of interest (COI) declarations, but leading publications have significant variation in their definitions and policies to ascertain COI. However, since many journals could not survive without the revenue generated by advertisements and reprint requests, journals themselves have a conflict. Should you stop reading journals? Absolutely not. Instead, you should use awareness of imperfections within the medical publishing world to develop strategies to overcome streams of misinformation.

The first strategy is to hone your critical appraisal skills. Developing expertise critically appraising medical research reports is just another skill that requires guided repetition to master. Remember when you first learned how to insert a chest tube? You probably watched somebody and then placed the next chest tube under supervision before eventually graduating to independence (see one, do one, teach one). Unfortunately, many EM residency graduates do not receive this exposure to EBM or knowledge translation during their post-graduate training. Interest groups, courses, and online list serves do exist to begin developing these EBM skills, but Table 2 (4) provides some general guidance as to when a study should be incorporated into your practice. At a minimum, users of the medical literature should understand that there are different levels of evidence and not all published studies with convincing results are ready for bedside application. In fact, those studies that are directly applicable to clinical care are mostly systematic review and the occasional randomized controlled trial.

Since many clinicians lack the time or energy to develop critical appraisal skills, the second strategy is to turn to trusted experts to do the leg work for you. Multiple sources of secondary peer reviewed information have been developed which are being reviewed in this issue of EPM. In general, secondary sources that help you interpret the abundant volumes of published data should provide the attributes detailed in Table 3.

In conclusion, the physician with healthy skepticism is cognizant of the potential flaws in medical research but not a laggard denying their patients best-evidence care. Busy clinicians have a variety of secondary peer reviewed sources available with variable levels of cost, financial conflicts, methodological rigor, external validity, and accessibility. Watching medical advances from the sideline is not an option during an era of intense healthcare scrutiny, but proactive knowledge translation is not overly difficult or time-consuming with the resources available.

Christopher R. Carpenter, MD, MSc, is the Director of Evidence Based Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, and is the Co-Chair, Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine

Scott Weingart, MD, is an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. He is also co-author of Emergency Medicine Decision Making: Critical Choices in Chaotic Environments (McGraw-Hill 2006)

REFERENCES

1. Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB; Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care, Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 260-273.

2. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature, 2nd Edition, Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ; 2008, McGraw-Hill.

3. Extrapolated from Table 11-1 in Emergency Medicine Decision Making: Critical Choices in Chaotic Environments, Weingart S, Wyer P; 2006, McGraw-Hill

4. Cone DC, Lewis RJ; Should this study change my practice? Acad Emerg Med 2003; 10: 417-422.

1 Comment

Thanks for this excellent article. Especially pointing out that skeptics still need to be avid and informed consumers of the literature – otherwise we are all sheep.