Diagnosing a patient with extraocular movement deficits.

A 32-year old woman presented to the emergency department with nausea and eye pain on upgaze, tunnel vision, ataxia, headache and blurry vision that developed two days before presentation. Her past medical history was significant for multiple sclerosis, hypertension, eczema, migraines and asthma. She noted that she received her third dose of interferon beta-1a three days before her symptoms began.

She described bilateral eye pain and nausea that was worse on up gaze and narrowing of her visual fields to very limited tunnel vision. Her headache was diffuse, constant, non-radiating and gradually worsening. She also reported photophobia, dizziness, loss of balance and feeling unsteady when walking. This progressed to blurry and double vision and inability to ambulate due to her ataxia. She was seen by Ophthalmology and reported a normal exam the day before her presentation to the Emergency Department.

Her medications included interferon beta-1a injections for her multiple sclerosis and amlodipine for her hypertension. She reported no history of similar symptoms with either her MS or her migraines. She had no allergies and was a full-time student. Physical examination revealed right homonymous inferior quadrantanopsia on binocular visual field testing. Monocular field testing revealed temporal deficits in the left eye. Extraocular movement testing revealed weak adduction of the affected eye and nystagmus with adduction of the contralateral eye, consistent with marked bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia.

She had significant blinking and eye strain during testing. Optic discs were unremarkable, and pupils were equal, round and reactive to light without an afferent pupillary defect. Facies were symmetric and facial sensation intact, but she did have collapsing weakness of left head turning and shoulder shrug with mild collapse of right head turning. She had no dysmetria of the upper extremities, but truncal ataxia was present. Aphasia and dysarthria were also absent. Laboratory diagnostics were unremarkable.

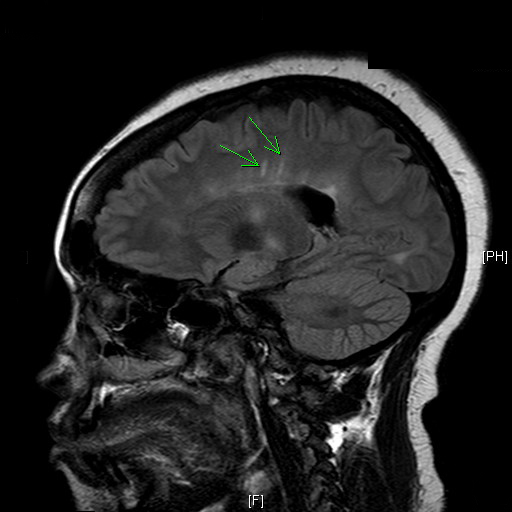

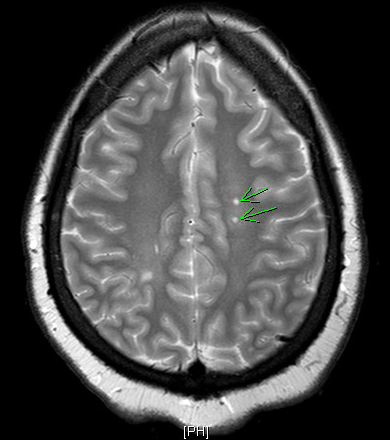

MRI of the brain with and without contrast was negative for acute MS lesions, but did show stable demyelinating disease consistent with MS. The MRI images demonstrated Dawson Fingers, a radiographic sign of demyelination characterized by linear plaques that run perpendicular to the lateral ventricles or corpus callosum. Typically reflecting periventricular inflammation, Dawson Fingers are relatively specific to multiple sclerosis.

What’s your diagnosis?

- Cerebrovascular Infarct

- Drug Toxicity

- Acute Multiple Sclerosis

- Infection

Answer: C — Acute Multiple Sclerosis

Discussion

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) is a gaze abnormality characterized by impaired horizontal eye movements, including weak adduction of the affected eye and nystagmus with abduction of the contralateral eye. Convergence is usually preserved, but patients may present with horizontal diplopia as well as difficulty tracking objects if the adduction weakness is severe. Dysconjugate eye movements result in vertigo, vision fatigue and loss of depth perception commonly associated with INO.

INO is the result of a lesion to the medial longitudinal fasciculus of the pons or midbrain. About 38% of cases are due to cerebrovascular infarct, 34% from MS and 28% from unusual cases such as trauma, herniation, infection, tumor, iatrogenic causes, hemorrhage and vasculitis.

Diagnosis is made by physical exam and MRI of the brain with and without contrast. Treatment consists of proper treatment of the underlying cause. Deficits usually resolve over a period of months except in the case of cerebrovascular infarcts — 63% of these patients will continue to have deficits after three years from onset of symptoms. Treatment with an eye patch may provide symptomatic relief.

Our patient’s INO was bilateral. One study found that approximately 46% of all cases of INO are bilateral, but this number increases to 73% when studying only MS-induced INO. While our patient’s MRI was negative for acute MS lesions, it is estimated that MRI carries a 5-25% false negative rate for acute MS plaque. After being treated with a short course of intravenous steroids followed by an oral taper, her extraocular movement deficits resolved, but she continued to have blurry vision and mild truncal ataxia on follow-up.

Differential Diagnosis

Cerebrovascular infarct is the most common cause of INO. These patients are typically older (>45 years old with an average age of 64) and symptoms are more often unilateral than MS induced INO. These patients also have more vascular risk factors than MS patients. The infarct is usually a small artery occlusion or lacunar disease stemming from the basilar artery, but large vessel occlusions can also cause INO.

Rarely, the use and toxicity of both prescription and illegal drugs can cause INO. These drugs include amitriptyline, ethanol, cocaine, benzodiazepines, immunosuppressant agents and carbamazepine. Like MS, these cases of INO are typically bilateral and resolve spontaneously with the cessation of the drug or reversal of toxicity. Suspicion for these drugs as the cause of INO should be raised if the patient admits to their use, particularly if the agent was recently started.

Infections can also cause INO. Toxoplasmosis, cysticercosis and viral encephalitis of the brainstem can cause INO in an extremely small number of individuals. Suspicion for these causes of INO should be raised in an immunocompromised patient with a diagnosis of AIDS. In immunocompetent patients, INO can rarely be caused by syphilis or tuberculosis induced meningitis. Septic shock can also cause INO if hypoperfusion causes brainstem infarction.

The Take-home Message

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is a gaze abnormality characterized by adduction weakness of the affected eye and nystagmus upon abduction of the unaffected eye. Prompt recognition and diagnosis of INO is imperative, as the most common causes are cerebrovascular infarct and multiple sclerosis; however, unusual causes of INO should also be considered. The age of the patient and presence of unilateral versus bilateral symptoms can help distinguish between the two primary causes. All patients with internuclear ophthalmoplegia should undergo MRI of the brain to determine cause.

REFERENCES:

Feroze KB, Wang J. Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441970/

Frohman TC, Frohman EM. Internuclear Ophthalmoparesis. UpToDate. Last updated Dec 04, 2017. Retrieved Nov 02, 2018 from www.uptodate.com.

Keane JR. Internuclear OphthalmoplegiaUnusual Causes in 114 of 410 Patients. Arch Neurol.2005;62(5):714–717. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.5.714

Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999: 503-4.

Palace J. Making the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2001;71:ii3-ii8.

Toral M, Haugsdal J, Wall M. Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia. EyeRounds.org. posted June 8, 2017; Available from: http://EyeRounds.org/cases/252-internuclear-ophthalmoplegia.htm.