Deciphering abdominal pain in an elderly patient.

The new intern approaches you with your next patient to staff: a 75 year-old female with abdominal pain. She has experienced diffuse abdominal pain for five days that is getting progressively worse. The patient has been nauseated with several episodes of non-bloody emesis and reports a subjective fever. She was seen at an urgent care several days ago, diagnosed with gastroenteritis, and given a prescription for an antiemetic, but is not improving. Her medical history includes diabetes mellitus, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, coronary artery disease, and is status post a cholecystectomy.

On physical exam, the vital signs are: BP 118/66, HR 96, RR 18, SpO2 96%, Temp 37 deg C. The patient appears uncomfortable, but is not in distress, has a regular rhythm, clear breath sounds, no CVA tenderness, moderate diffuse abdominal tenderness that’s slightly worse in the lower abdomen, no extremity edema and a normal neurologic exam.

The triage desk ordered urine while your patient was waiting for her room. Her results are: 10 WBCs, 5 RBCs, small leukocyte esterase, small ketones and no nitrites.

When asked for her differential, the intern said, “Well, this is probably a UTI. But I suppose it could also be a renal stone, gastroenteritis, ovarian or uterine cancer, or pancreatitis. But I think given her urine results, we can just give her antibiotics and discharge her.”

After discussing an expanded differential including cardiac and pulmonary causes as well as a broader range of abdominal diagnoses, you have the intern order labs and medications. Radiology requires recent lab work to perform a CT scan so, realizing it may take a while to get results, you set up the ultrasound machine since you know the high specificity for many disease processes.

When you examine the patient, you ask her to point with one finger where the pain is the most intense and she says “all over” while she draws a circle on her abdomen with her hand.

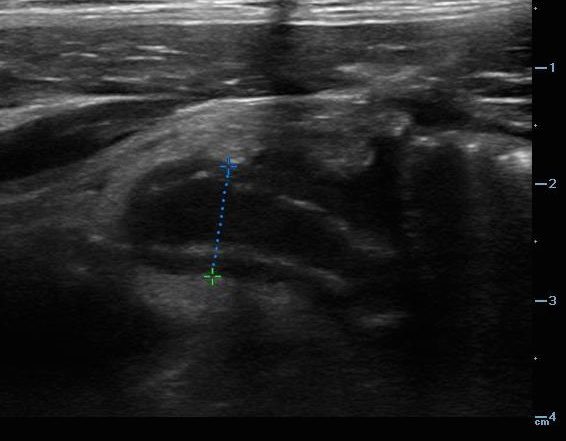

With the intern’s assistance, you ultrasound her aorta and kidneys, both of which appear to be normal. As you finish scanning her bladder, you notice that she seems to wince more as the probe comes closer to her right lower abdomen. You slide the probe over, take a measurement, and ask your intern, “What is our diagnosis?”

Dilated appendix measuring 9.5 mm with wall edema, consistent with appendicitis.

She looks at the screen and said, “I haven’t had much experience with ultrasound. I’m not sure what I’m looking at.” You show her some anatomy and slide back over the appendix. You point out the dilated structure and appendicolith with posterior shadowing. She looks a little surprised and said, “I didn’t even consider appendicitis given her age!” She pages the surgery team and your patient is taken to the OR a few hours later after a CT scan confirms her diagnosis.

Dilated appendix with appendicolith and posterior shadowing.

Teaching Pearls:

- How to do it:

Choose the high frequency linear probe or a low frequency curvilinear probe, depending on the depth you need for the patient’s body habitus. Your patient should lay supine on the bed and place the probe at the spot of maximum tenderness. The appendix is often found more superficial than most people imagine. It is possible to see a normal appendix, yet this can be difficult — it is more common in children than adults. The appendix should arise from the base of the cecum as a blind-ending tubular structure that is compressible, has peristalsis and displays a wall thickness of 2 mm or less. Often the appendix is located just medial to the psoas muscle and just superior to the iliac vessels. It is important to visualize the appendix in two planes. A target sign is classic for visualization in a transverse plane.

Normal RLQ anatomy. Seen are the psoas muscle, abdominal wall muscles, iliac artery (A), and iliac vein (V).

Dilated appendix measuring > 1 cm, seen in transverse view. Also known as the target sign.

- Troubleshooting:

Slow, meticulous sweeping movements near the area of maximal tenderness with graded compression is the best way to locate the non-compressible, acutely inflamed appendix. Graded compression uses steady pressure to compress normal bowel, reduce bowel gas and brings the appendix closer to the abdominal wall. The ascending colon can also be followed proximally to locate the cecum and appendix insertion. Alternatively, the psoas muscle and iliac vessels can be located and a sweep can be done of this area to look for the appendix. Appendicitis is most easily identified when an appendicolith is present given this clear echogenicity and posterior acoustic shadowing.

- Diagnostic Criteria:

An inflamed appendix is represented by a non-compressible, blind-ending tubular structure. This should be easily visualized in both a short and long axis view. There will be no peristalsis, which differentiates it from small bowel. A diameter of > 6 mm, including wall edema, is consistent with acute appendicitis. Other features that can help further support the diagnosis include: appendicolith, periappendiceal fluid or abscess, or periappendiceal fat stranding.

Dilated appendix measuring 1.3 cm with surrounding fat stranding.

- Limitations and Pitfalls:

While diagnosing appendicitis can be quite straightforward, things like enlarged body habitus, bowel gas, retrocecal location, appendiceal rupture and the patient’s pain or guarding can make adequate imaging difficult. Ultrasound is not as sensitive as CT, but specificity is quite high, and can potentially limit exposure to ionizing radiation. When measuring the appendix, measure outer wall to outer wall including any wall edema. Visualize the entire length of the appendix so as to evaluate for tip appendicitis. This is a rule-in test, not a rule-out test; obtain further imaging if clinical concern remains despite a non-diagnostic ultrasound.

- Practice!

Appendicitis is the most common cause of acute abdominal pain requiring surgery in patients under 50 years old. It is important to be able to evaluate for this with bedside ultrasound. While you can find appendicitis on your first attempt, practice does greatly improve your ability to locate and accurately characterize the appendix since ultrasound visualization is operator-dependent. There is minimal downside to scanning, and you have the potential to expedite diagnosis, surgical consultation, antibiotics, as well as reduce radiation and speed up ED disposition.

References:

Cole MA, M. N. (2011). Evidence-based management of suspected appendicitis in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Practice, 13(10), 1-32. Retrieved from ebmedicine.net

Elikashvili I, Tay E, Tsung JW. The effect of point-of-care ultrasonography on emergency department length of stay and computed tomography utilization in children with suspected appendicitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014 Feb;21(2):163-170.

Fox JC, Solley M, Anderson CL, et al. Prospective evaluation of emergency physician performed bedside ultrasound to detect appendicitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008 Apr;15(2):80-5.

Mallin M, Craven P, Ockerse P, et al. Diagnosis of appendicitis by bedside ultrasound in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2015 Mar;33(3):430-2.

Paulson EK, K. M. (2003, January 16). Suspected Appendicitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(3), 236-42.

http://www.thepocusatlas.com/new-blog/appendicitis