A disturbing vital sign can often be worked up quickly with ultrasound… but not always

“I have a new one for you.” As you turn your head toward the familiar voice of your triage nurse, you see she is briskly rolling a gurney containing your new patient into the critical care area of your ED.

“What’s going on?” you ask, quickly looking over the patient, a petite woman who appears to be sitting comfortably in bed in no acute distress.

Without missing a beat, your nurse continues to wheel the patient rapidly into the critical care bay. “This is a 54-year-old female with a history of diabetes presenting with worsening fatigue and dizziness over the past week. She also had a syncopal episode four days ago. She was hypotensive in triage, 73/52.”

Although you know the answer, you ask anyway, “Did you recheck the blood pressure?”

“Of course, and we used a different cuff as well, with the same result,” she responds. You grab the patient’s chart from the nurse and scan the triage sheet for any other vital sign abnormalities. You find no tachycardia, no fever, good oxygen saturation on room air, and a normal respiratory rate.

As the patient gets wheeled into place within her room, the other critical care nurses spring into action getting the patient hooked up to the cardiopulmonary monitor and into a hospital gown. As they work, you turn your attention to the patient and quickly run through her history of present illness and past medical history.

She relays a history similar to the one provided by the triage nurse: four days of intermittent light-headedness that is worse with activity, and a single episode of “blacking out” four days ago. But she reports no chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, dark stool or other complaints.

As you finish up your interview, you ask the nurse to recheck the blood pressure. She hits the proper button and the cuff on the patient’s left arm instantaneously starts to inflate, then slowly deflates with rhythmic pulsations to reveal a pressure of 74/51. The patient is still hypotensive, but continues to appear in no apparent distress.

Once on the monitor, you note that the patient appears to be in normal sinus rhythm. You move on to the physical exam, listening intently to the heart for murmurs, observing the neck for JVD, checking for signs of anemia, taking note of the moist mucous membranes and lack of significant edema in the lower extremities. You find nothing obvious on exam. You even perform a rectal and check the stool for blood, but the sample reveals itself to be Hemoccult negative, normal brown stool. You notice the patient already has an IV in the right antecubital fossa before any of the critical care nurses had an opportunity to place one. Pointing to the IV, you ask the nurse, “Did she come in by EMS?”

Unveiling the Differential

The nurse smirks, “No, one of the eager nursing students put that in as we were getting triage vitals.” Being somewhat relieved to already have intravenous access on the patient, you order a fluid bolus. As you sit down at the computer to order a barrage of laboratory studies and imaging, the differential continues to scroll through your head. Hypovolemia? Left ventricular dysfunction? Valve abnormalities? Pericardial effusion? Large pulmonary embolism? Tension pneumothorax? Medication side effect? As you ponder the possibilities, you quickly sign your orders and run to grab your bedside ultrasound machine, knowing you can probably diagnose the problem before you get the results of a single lab value.

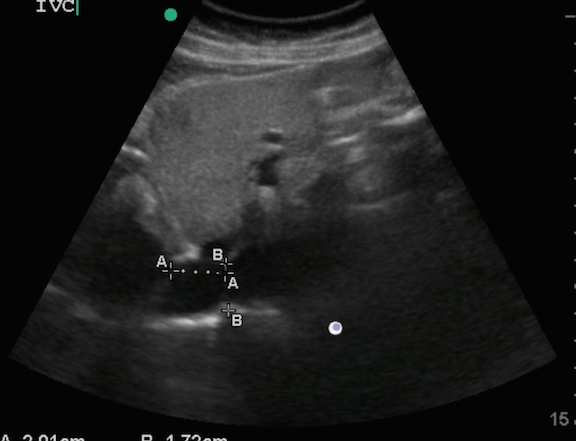

As you are setting up, the ED tech obtains an EKG, which is essentially normal. With the patient data entered into the ultrasound computer, you grab your curvilinear probe and first take a look at the inferior vena cava to determine if the patient is hypovolemic. Luckily, due to the patient’s petite build, you get an excellent view of the IVC and take the proper measurements (Figure 1 above title: Point of care ultrasound of the patient’s IVC in B-mode).

With your probe over the patient’s IVC, you switch into M-mode. You have the patient take a deep breath, but the IVC does not collapse (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Point of care ultrasound of the patient’s IVC in M-mode

Her intravascular status does not appear to be the problem, so you continue your CORE scan to try to find any acute, reversible abnormalities. You take a look at her lungs and she does not have a pneumothorax, pulmonary edema, or obvious infiltrate. You get a great apical 4-chamber view of her heart (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Apical 4-chamber view of the heart

You carefully evaluate the heart for any obvious abnormalities. There is no pericardial effusion, dilated ventricles, decreased contractility, or obvious clots in the chambers. The mitral valves and aortic valves appear grossly normal. In fact, you are relieved that you see a perfectly normal looking heart.

As part of your CORE scan, you assess for any intraperitoneal free fluid and you scan through the abdominal aorta from the subxiphoid area down through the iliac arteriess bilaterally. The patient has no intra-abdominal free fluid and her aorta appears to be less than 2 cm all the way through (Figure 4). You scan through her kidneys, liver, and spleen and you still don’t find any acute or obvious abnormalities.

Figure 4: The patient’s aorta appears to be less than 2 cm all the way through

As you try to make sense of the normal ultrasound findings in the context of hypotension, you hear the nurse exclaim, “The pressure just cycled, she is now 65/46!” At this, the patient begins to look concerned. You ask how she is feeling. She replies that she’s okay as the nurse points to two empty IV bags of normal saline hanging above the patient and says, “We already dumped two liters into her and her pressure is no better. Do you want me to hang any pressors?”

Why So Hypotensive?

You continue to contemplate what could be going on with the patient. If she is not volume depleted and does not have any cardiac, thoracic, major abdominal or aortic abnormalities, then why is she so hypotensive? Why isn’t she tachycardic? She is not on beta-blockers or other medicines that would suppress tachycardia. Shouldn’t she be more symptomatic? Finding no obvious answer, you decide to start the process over again.

You turn to your triage nurse who stuck around to help resuscitate the patient.

“You tried different blood pressure cuffs, correct?

”Yes.”

“And you checked both arms?”

“Yes,” she states confidently, but before you can ask your next question, she corrects herself, “Oh wait, no! The nursing student was starting an IV on the right arm while we were checking the blood pressure.”

Before she finishes the sentence, you take off the patient’s cuff from her left arm and hand it across the bed to the nurse on the other side telling her to check the other arm quickly.

After a brief moment of silence, the monitor spits out a number: 126/84. Puzzled, you again check the left: 67/42. You go back to the right: 123/86. You are inclined to check both radial pulses and find the left slightly weaker than the right. Now that you’ve become concerned about a vascular abnormality, you order a CT Angiogram of the neck and chest, which reveals severe stenosis of the left subclavian artery (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5

Figure 6

It turns out when you expand on the history that the “activity” that was triggering her symptoms has been scooping ice-cream at her new job, and she is left handed! You wonder if you could have made this diagnosis with your ultrasound machine had you looked.

You admit the patient for subclavian stenosis with likely subclavian steal phenomenon, and she receives an arterial stent from interventional radiology that night.

Your patient thanks you for the excellent care and extra attention you provided her, and your intensivist is thrilled that you solved the case and saved the patient from an unnecessary ICU admission for her “hypotension.”

Pearls & Pitfalls for Assessing the Hypotensive Patient

Point-of-care ultrasound is a very useful tool to use in the assessment of any patient who presents with undifferentiated hypotension. You can make the critical diagnosis that may save a patient’s life, or you may rule-out acute etiologies that are high on your list of differential diagnoses.

The Concentrated Overview of Resuscitative Efforts (CORE) exam is a set of focused ultrasound evaluations targeted at evaluating the major potential causes of deterioration in a decompensating patient.

Here’s some tips and tactics for maximizing CORE:

- During the CORE scan, evaluate the patient for conditions that you can emergently treat or reverse. Use the CORE scan to assess and reassess your critical patients.

- Scan the heart to determine if the patient has a large anechoic stripe around the heart that could be a pericardial effusion leading to cardiac tamponade. Look for signs of right atrial or end-diastolic right ventricular collapse that may prompt an emergent ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis.

- Assess the contractility of the ventricular walls of the heart to assess for any wall motion abnormalities which may indicate myocardial ischemia or infarct.

- Calculate or estimate the ejection fraction or fractional shortening and look at the valves for obvious stenosis or regurgitation.

- Determine if there is any significant right ventricular or right atrial dilation that may indicate right heart strain from an acute saddle pulmonary embolism. You may see a large intra-atrial or intra-ventricular clot ready to take off into the pulmonary artery.

- Assess the lungs for a pneumothorax, pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or pleural fluid that may be contributing to your patient’s decompensation. If you find any of these abnormalities, initiate aggressive treatment.

- Scan through the patient’s abdominal aorta to evaluate for a potential abdominal aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection.

- Take measurements of the IVC with and without sniffing to determine if the patient is hypovolemic with >50% collapse during inspiration.

- Scan through the abdomen to rule-out intra-abdominal free fluid if liver failure or trauma is a possibility.

- Perform an extremity DVT scan if your patient is at risk for clot formation and propagation to more proximal sites.

The more you practice point-of-care ultrasound, the better you will become at using it to help your patients. Learn to differentiate normal findings from abnormal sonographic clues. Check out the ultrasound image library at EMresource and/or SonoSupport for a comprehensive overview on how you can incorporate ultrasound into your clinical practice.

2 Comments

Humble thanks for this outstanding Case

Truly outstanding Please consider sending me a review copy of a book on this subject that any of the authors has written for me to write a review to 1830 Waters Edge Drive Johnson City, Tennessee

37604 – 8316

Great job getting to the point of the matter.

The importance of point of care US couple with good physical exam and history goes go a long way.