How does it compare to the current COVID-19 outbreak?

In striking similarity to the current Coronavirus pandemic, the Spanish Influenza of 1918 was devastating, reaching all corners of the world and killing an estimated 20 million to 50 million people. As with the current pandemic, reports of illness and mortality due to influenza were censored or minimized in many countries.

Since Spain was a neutral country during World War I, reports of illness were not censored, creating the impression that Spain was disproportionately affected by the virus and leading to the name “Spanish Flu.” We now know that the Spanish Flu was a novel strain of H1N1 influenza believed to have originated in China as an avian variant.

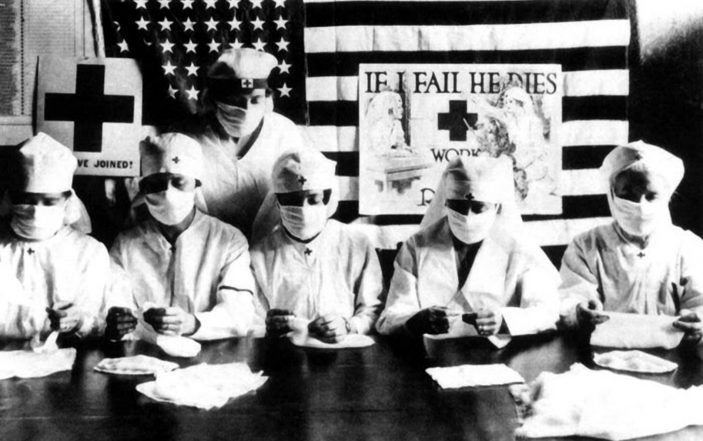

As a result of pressure from Health Departments nationwide, masks became commonplace with city workers such as sanitation, police and trolley conductorettes. Shoppers also wore masks in public.

History

To understand how the Spanish Flu wreaked such global havoc, it is necessary to understand the events taking place at the time. World War I was coming to an end and the United States had begun fully participating with troops on the front lines in Europe. In the spring of 1918, there were sporadic outbreaks of a flu-like illness across the U.S.

One large outbreak occurred at Camp Funston, Kansas where hundreds of soldiers were infected. Over the summer of 1918, there seemed to be a lull in infections as soldiers and workers from around the world descended upon the Western Front of WW I. By early fall of 1918, WW I ended and soldiers returned to their homes across the globe, carrying with them a virus that would kill millions more than the war.

As the spread of influenza worsened, large makeshift hospitals were created in fields and in convention centers.

Akin to modern day global travel, the second half of 1918 saw an immense amount of travel as soldiers and support personnel traversed the world. Social distancing made a difference in the prior pandemic as well. For example, on Sept. 28 1918, despite seeing a startling increase in deadly flu cases, Philadelphia held a “Liberty Loan” parade to raise support for the war efforts.

More than 200,000 people attended the parade. Within days, thousands across the city were sickened and the city’s hospitals were overflowing. Six weeks later, over 12,000 had died from influenza. By contrast, St. Louis cancelled a similar parade and instituted social distancing precautions earlier, resulting in 1/8 of the number of influenza cases and deaths.

Fallout

The Spanish Flu raged into 1919 and is estimated to have infected one-fifth of the world’s population. In the U.S., roughly 675,000 people died in the nearly two-year pandemic, 10 times the number of American soldiers that died in WW I.

Particularly affected were younger adults aged 20-40, with males being especially susceptible. The immediate aftermath of the Spanish Flu caused severe economic and social devastation.

In the following years, several positive effects of the pandemic occurred. Both the U.S. and world’s economy experienced significant growth due to a combination of effects from WWI and the Spanish Flu. Additionally, the U.S. healthcare system was drastically changed. The 1920s saw a dramatic shift toward “population health,” including the founding of the precursor to today’s World Health Organization (WHO).

Nurses from the Red Cross banded together to make face masks to distribute to the public. In some military installations, masks were heat sterilized for re-use.

Nurse Letter Sidebar

An October 1918 letter from a volunteer nurse to a friend described many events of the time:

As many as 90 people die every day here with the “Flu.” Soldiers too, are dying by the dozens.

Our chief duties were to give medicines to the patients, take temperatures, fix ice packs, feed them at “eating time,” rub their back or chest with camphorated sweet oil, make egg-nogs and a whole string of other things I can’t begin to name.

Four of the officers of whom I had charge, died. Two of them were married and called for their wife nearly all the time. It was sure pitiful to see them die.

Two German spies, posing as doctors, were caught giving these influenza germs to the soldiers and they were shot last Saturday morning at sunrise.

Really, they are certainly “hard up” for nurses—even [I] can volunteer as a nurse in a camp or in Washington.

The Washington Monument (555ft. high) is within walking distance of the Interior Department (where we work) and … we are planning to go up in the elevator … to look over the city … but the place is closed temporarily, on account of this “Flu.” All the schools, churches, theaters, dancing halls, etc., are closed here also.

2 Comments

The Rockefeller Institute used an untested bacterial meningitis vaccination on troops around the world just prior to the outbreak. It was developed through horses and never tested on humans. This information was suppressed until rediscovered recently. Perhaps 50 million people died as the result of medical hubris.

Over 96% of the deaths were from bacterial pneumonia. It killed young people primarily and very quickly. A terrible death.

1918 H1N1 was first recognized in the US, as your article noted, at Camp Funston in Kansas where troops were being trained for WWI. Patient zero from that outbreak is known; a cook at the camp. He and most other soldiers who were infected that spring survived. The virus quiesced during the summer, as influenza, coronaviruses and other similar viruses often do.

However, troops were then further packed together as they were transported via ships to Europe and then further congregated in the trenches of WW1 battlefields. These actions created a ‘host abundant’ situation that allowed H1N1, in the process of producing mutant strains as all such viruses do, to produce more lethal strains that could compete successfully in the host abundant condition, as in such conditions, survivability of the host is not an issue.

Thus, by the time the troops were returned to the US, predominant strains of H1N1 had become lethal with the results that your article notes beginning in the fall of 1918.

What is important to realize is that our actions in determining host-abundant and host-restricted environments will modify the virus genome thus changing the lethality of a virus. If the host environment is host-restricted, such as in social distancing, more lethal viral strains are less successful as if they debilitate and/or kill their host thus reducing effective viral spread, that strain is less successful. In a host-restricted environment, more successful viral strains are those that make the host less ill or asymptomatic, thus allowing for increased viral spread, making that viral strain more competitive and more successful.

The ‘take home’ is that we can modify the SARS-CoV-2 virus that will return this fall by our social actions this spring and summer.

Harry W Severance, MD, FACEP