A 51-year-old male with a past medical history significant for polysubstance abuse presented to the emergency department for altered mental status and peripheral edema.

According to EMS, they were originally dispatched for a patient with bilateral leg edema. EMS found the patient altered and obtained a blood glucose in the 50’s. The patient was given Dextrose enroute to the emergency department, but did not show significant improvement of his symptoms. An EKG obtained by EMS enroute showed ST elevations in the inferior leads as well as some lateral leads.

Upon arrival in the emergency department, the patient was alert and oriented x 2. He complained of left sided intermittent chest pain associated with shortness of breath for the past two weeks. He denied fever, chills or a productive cough. He endorsed heroin use 2 hours prior for pain relief from his chest pain.

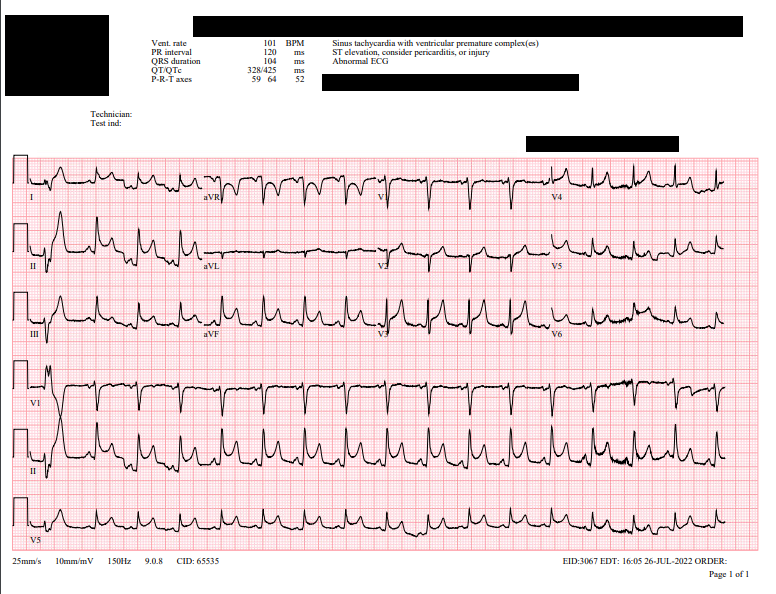

Physical examination was significant for a diaphoretic, disheveled patient in acute respiratory distress with absent left sided breath sounds as well as pinpoint pupils and bilateral 3+ pitting edema. His vital signs were as follows: BP: 126/83 Temp: 97.6 F, HR: 100, RR 15, SpO2: 92% RA. An EKG upon arrival was read as sinus tachycardia, rate 101, normal axis, PR: 120, QTC 425, ST elevation in II, III, AVF, V3-V6 with reciprocal changes in AVR (figure 1).

Figure 1:ECG sinus tachycardia, rate 101, normal axis, PR: 120, QTC 425, ST elevation in II, III, AVF, V3-V6 with reciprocal changes in AVR

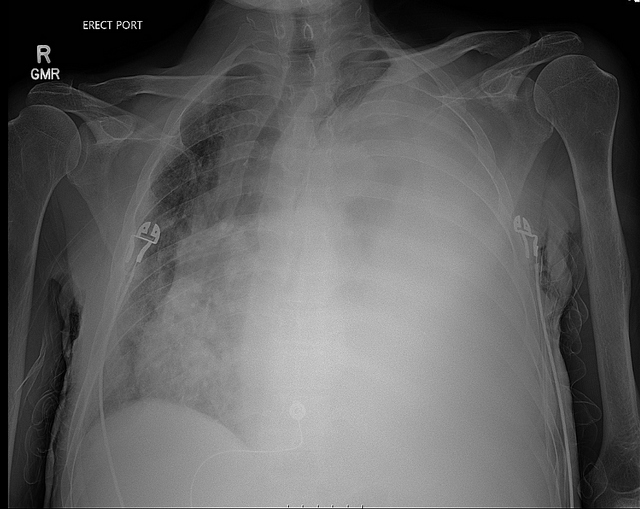

After obtaining vitals, a stat chest x-ray was obtained and showed complete opacification of the left hemithorax with rightward mediastinal shift and minimal aeration of the left apex (figure 2):

Figure 2: AP CXR showing complete opacification of the left hemithorax with rightward upward mediastinal shift

Given the ST segment elevation on his EKG, a bedside echocardiogram was performed which was significant for a small pericardial effusion without tamponade physiology, a normal EF, and no evidence of right heart strain. Lab work was significant for a lactate of 9.8, pH of 7.175, WBC of 24.4 with a left shift, hyponatremia of 123, hyperkalemia of 6.4, BUN 60, Creatinine 2.04, anion gap of 25, BNP 345, ALT 387 and AST 486.

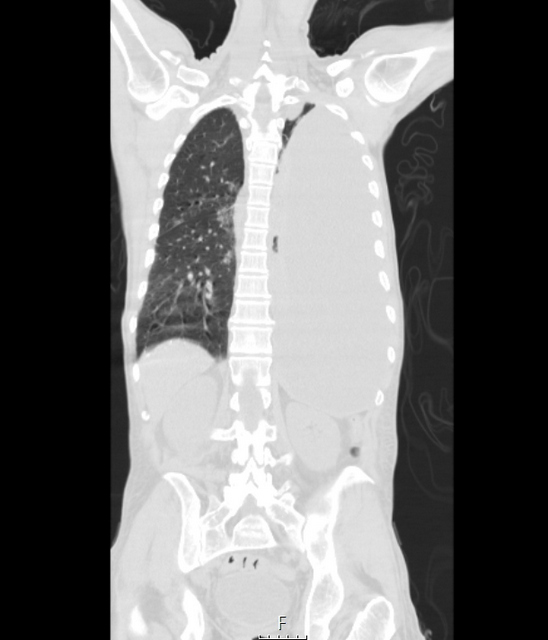

The patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics for presumed sepsis: Vancomycin and Zosyn. IV fluids were administered as well as a hyperkalemia cocktail of insulin, dextrose, and calcium gluconate, and sodium polystyrene. Given the large pleural effusion with mediastinal shift, a stat CT chest was performed to further characterize the fluid; this confirmed a large left effusion with significant right mediastinal shift (figure 3).

Figure 3.CT chest, coronal view: large left pleural effusion with significant rightward mediastinal shift

A decision was made to insert a left sided chest tube due to the abnormal CXR and CT as well as the acute distress of the patient. Upon a lateral chest wall incision, a foul smelling, purulent fluid was released under pressure with subsequent drainage of approximately 3L of the same fluids (figure 4a,b) figure 4b movie)

Figure 4a,b: initial incision of the lateral chest wall with subsequent movie after entering the pleural cavity

After placement, the patient had significant improvement of his respiratory distress. He was admitted to the medical stepdown unit for further monitoring and management. Pleural fluid studies demonstrated a pH of 6.16, WBC 501K, RBC 240K, 77% lymphocytes and 23% monocytes. A gram stain was performed which revealed gram positive cocci in chains consistent with group A strep which was pansensitive.

Discussion

Empyema is the collection of purulent fluid in the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall. There are multiple different avenues in which empyema may arise including but not limited to: pneumonia, trauma, recent thoracic surgery, and mediastinal or esophageal infection.

Unlike the case presented, empyema usually presents with vague symptoms such as malaise, fever, or weight loss. Given the ambiguity of symptoms, it can be identified later in hospital stays leading to a delay in treatment. Review of the literature suggests elevated morbidity and mortality with 20 to 30% of cases requiring further surgery or death within the first year.

Diagnosis is achieved first by detailed physical examination which may be significant for dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds or rales. Primary diagnostic tools include a chest x-ray as well as lab work.

Once “white-out” is identified on a chest x-ray and hemodynamic stability allows it, consider utilizing a CT scan to further characterize the fluid as well as identifying loculations and ideal chest tube insertion location. Patients should be started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Chest tube drainage of the empyema can be achieved within the emergency department.

Conclusion:

The patient in the above case was admitted to the medical stepdown unit. The patient’s course was complicated by atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response which was treated with an amiodarone drip. He then developed a pericardial effusion and was started on NSAID treatments. Repeat CT chest showed significant improvement of pleural effusion, and the chest tube was removed. Unfortunately, patient immediately left the inpatient service against medical advice and was lost to follow-up.

Citation:

A.D. Ferguson, R.J. Prescott, J.B. Selkon, D. Watson, C.R. Swinburn, The clinical course and management of thoracic empyema, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 89, Issue 4, April 1996, Pages 285–290, https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/89.4.285

Garvia V, Paul M. Empyema. [Updated 2023 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459237/

Figure 1:ECG sinus tachycardia, rate 101, normal axis, PR: 120, QTC 425, ST elevation in II, III, AVF, V3-V6 with reciprocal changes in AVR