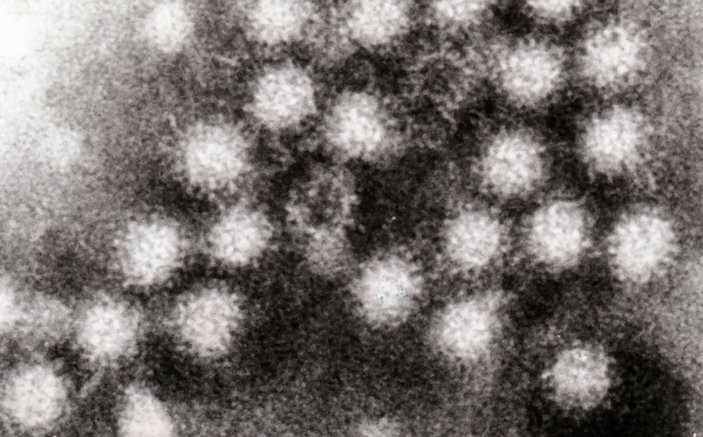

Norovirus can ruin your whole week – and cripple your department. Here’s what you need to know to prepare.

I confess I always associated Norovirus with cruise ships. While it is the causative agent for 90% of diarrheal outbreaks on cruises [1], it is most commonly reported in healthcare facilities, brought in by patients or visitors (or staff) who may not be symptomatic. Infections peak in winter (in fact, infections are often called the Winter Vomiting Bug). A little fun trivia: technically, Norovirus is the genus name, and the species is called Norwalk virus, but since it’s the only species in this genus, the terms are often used interchangeably.

Whatever you want to call it, when it hits your ED, the results can be catastrophic.

The problem is that Norovirus is extremely contagious. Fewer than 20 virus particles have been shown to cause infection. Transmission of this bug is common through the fecal-oral route, sure, but doesn’t depend on direct contact. Aerosolized transmission is possible, through toilet flushes or projectile vomit. In fact one case study showed a single person at a restaurant, vomiting onto the floor, led to dozens of infections, as far away as four tables over (a ceiling fan was felt to contribute to the spread after a food borne route had been ruled out).

The symptoms themselves are almost always well managed with supportive care – most patients experience vomit and diarrhea, with nearly half also experiencing fever or abdominal pain (or both). Most people develop symptoms between 24-48 hours and find symptoms subsiding by 72 hours, though later onset is possible. Before PCR, for community outbreaks, epidemiologists and ID relied on Kaplan criteria to make the diagnosis of Norovirus infection (more than half the symptomatic patients have vomiting, average incubation 25-48h, average duration of illness 12-60 hours, and no pathogenic bacteria isolated from stool). However if it’s wintertime and there’s a lot of patients and staff vomiting, it’s a safe bet it’s Norovirus; PCR can give a definitive answer within half a day.

So the disease course is short and easy to manage, but that’s about the only good news. It can spread like wildfire through ED patients and staff and the virus survives up to a week on surfaces, across a wide range of temperatures. Without specific instructions, doctors and nurses who are showing symptoms may tough it out for the rest of their shift, only to infect many others. Once the outbreak is recognized, symptomatic staff are sent home – and CDC guidelines say they shouldn’t come back until 48 hours after the resolution of symptoms. Departments can see huge fractions of their staff out for days. Also, you can expect hospital-wide broadcast warnings for students and non-essential staff to avoid entering your department until the outbreak subsides. What’s worse is that shedding of virus can continue for weeks after symptoms subside (though contagiousness seems to drop off 2-3 days after recovery). Reinfection down the road is possible, as virus strains can exhibit impressive diversity. Patients with symptoms should be moved to single-occupancy contact isolation or, failing that, at least cohorted.

Gloves are of course important in examining patients, particularly those with GI symptoms; it’s also important to remove the gloves as soon as the exam is over, and not to touch anything on the way to the trash receptacle.

Alcohol gel dispensers, so ubiquitous in hospitals now, can’t be considered first-line for hand cleaning during outbreaks. The alcohol can’t achieve sufficient log reduction in virus counts to limit transmission, particularly when “soil” or “filth” (bits of vomit or poop) remain on hands. So, it’s got to be hand washing – preferably faucets with foot pedals or motion-control activation.

The CDC also recommends a robust surface disinfection program, with bleach or products from List G (not ammonia), targeting the highest trafficked areas, moving from likely unaffected areas to affected areas.

This process is disruptive and expensive. Whole sections of the ED need to be closed for bleaching (or steam-cleaning, for furniture) and the ED is likely short-staffed, to boot. Even when staff returns, things may not quite go back to normal. Sinks and bathrooms may be put out of commission temporarily for upgrades; staff lounges may be closed or re-located. Taped-up signs on the walls, displaying common phone numbers and protocols, are all torn down. Folks from Infectious Disease (or external regulatory agencies) may be auditing the department and staff practices, to make sure this don’t happen again. On the plus side, you and your team may become a bit more obsessive about hand-washing before and after each patient encounter, and using bleach-wipes on your workspace more regularly. And it might be a while before you can nonchalantly approach a vomiting patient again.

REFERENCES

- http://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/trends-outbreaks.html

- Marks et al, Evidence for airborne transmission of Norwalk-like virus in a hotel restaurant. Epidemiol. Infect. 2000. 124:481-487.

- Barclay et al. Infection control for norovirus. Clin Microbiol. Infect. 2014 20(8):731-740.

Image by Graham Beards at English Wikipedia