Emergency physicians may be the “jack of all trades” but we are the kings and queens of conflict management. If we define conflict as the simple mismatch between two parties’ expectations, EPs start holding court before we have even buttoned up our white coats.

Interpersonal conflict is a major part of every ED shift. How we handle it could define our careers.

Interpersonal conflict is a major part of every ED shift. How we handle it could define our careers.

Emergency physicians may be the “jack of all trades” but we are the kings and queens of conflict management. If we define conflict as the simple mismatch between two parties’ expectations, EPs start holding court before we have even buttoned up our white coats. The spectrum of our conflict ranges from ubiquitous inconveniences, like asking the orderly to restock the throat cultures, to the distressing verbal barrage of an unhappy patient or consultant.

In 2009, the Joint Commission put conflict and its successful resolution officially on its radar. They commented that 65% of reported sentinel events from 1995-2004 were directly linked to poor communication issues and unveiled two new hospital requirements: “The hospital/organization has a code of conduct that defines acceptable and disruptive and inappropriate behaviors” and “Leaders create and implement a process for managing disruptive and inappropriate behaviors.”

If you question that a squabble at the nursing station could snowball into a significant patient safety issue, look to the 2003 study done by the Institute for Safe Medication Practice. They surveyed 2095 health care providers and found that about half of nurses answered that they had altered the way they handled questions concerning medication orders due to previous conflict and that 7% admitted to committing a known medication error in the past year where intimidation played a significant role. What can we as EPs learn from this study? If we curse and slam down a chart after our computer crashes, that new nurse may not feel real comfortable approaching us directly about the heparin order we just entered erroneously.

As Thomas (Critical Care Medicine 2003) discovered, physicians may also generously overestimate their own communication skills. He asked 90 physicians and 230 nurses how well they rated their communication and collaboration with each other. While doctors rated their communication with nurses “high” 73% of the time, nurses rated their communication “high” with those same doctors only 33% of the time.

Like the above study, much of the literature concerning medical conflict is based in ICUs. The 2009 Conflicus Study (Azoulay American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2009) is a large European study which examined the frequency and severity of conflict of 323 hospital ICUs in 24 countries. They found that 71% of surveyed respondents reported conflict, with 53% perceiving it as severe. Conflict was most commonly associated between physicians and nurses (33%) and usually was expressed as personal animosity, mistrust or communication gaps. In other words, a large number of our ICU colleagues are spending a good portion of their working life with people who they mistrust and view with personal animosity. Yikes! As ICU and ERs share a lot of the same stressors, it bears investigating how conflict impacts emergency medicine.

The EPM Conflict Study

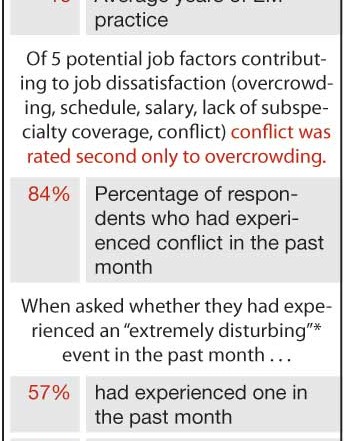

Based loosely on the Conflicus Study, EPM developed a survey to explore conflict and communication issues in the ED. As a former academic researcher, I fully disclaim that this is a reader’s survey with all the inherent flaws associated with one (nonrandom, voluntary, varied response rate, etc.) Nonetheless, the nearly 600 responses are worth exploring if for no other reason than to spark discussion and promote further research in this oft-overlooked subject.

Although the survey’s numerical data certainly suggests that conflict plays a big role in the life of many EPs, what was equally striking about the survey were the more than 100 write-in comments reinforcing the emotional impact of workplace conflict.

As a group, EPs seem to be most challenged by distressing conflict with patients. “People act in ways in the ED that would get them arrested anywhere else,” wrote one respondent. Concerns surrounding this conflict included: unrealistic expectations, diminishing respect for medical personnel, drug seeking behavior, and disagreement over elderly dispositions. As if that were not enough, one reader discovered a whole new sprouting area of discontent: “Our society is astonishingly empowering our patients’ ability to complain in a public forum, like Facebook, with no opportunity for fairness, rebuttal, or common sense.”

Conflict around consultants seemed to incite the most colorful survey responses and mostly centered on the lack of professional collegiality and disagreement concerning patient responsibilities. “I am done being yelled at, humiliated and brushed aside by consultants,” wrote one physician. “What really frosts me is when consultants ignore standards of care for our patients, and take that out on me and my colleagues,” wrote another. And finally, “We are not the police of the hospital and lazy doctors are the bane of my existence.” One reader commented on the direct link of these difficult interactions to patient care: ”… the more times [I have conflict with] any individual doctor or if it is a series of poor interactions with other physicians, I become leery of making phone calls. This delays patient care and is not good, but is self protective.”

Concerning their relationship with administration, several readers commented on an apparent disconnect between their department’s and their institution’s priorities. “There is an inherent conflict in that the docs have responsibility with little power and the hospital/administration/nursing have little responsibility and lots of power,” wrote a respondent. “I, and my partners, left hospital-based emergency medicine,” wrote another, “due to continued conflict with administration over the ‘blame game’ and their inability to see even the simplest solutions to the patient flow problems.” Conflict with administration seemed to be particularly sensitive around patient satisfaction scores. “Administrators and Press-Ganey reports are the root of all evil. Medicine is supposed to be a profession, not a service industry,” said one EP. “The current model of customer service based medicine has allowed the ‘kids to drive the bus’,” said another. Other challenges that appeared to be very institution specific included: violence and security related issues, ER contract competition, and appropriate use of physician extenders.

Although there were no glaring gender dif

ferences in responses, a few comments suggest that at least some female EPs are still challenged with unique issues surrounding gender and equity. “They (the nurses) gripe about the guys but they virtually knife women in the back,” wrote one female emergency physician. “As a women,” wrote another respondent, “I’m held to a different standard (often a higher one) for tone, body posture and interactions. The guys are allowed to do/say things and in a way that would never be tolerated if I were to do so.”

Readers reported that they had very little official training in conflict management, yet they recognized it as an essential skill for an EP. “[Conflict management] may be #1 for career satisfaction,” said one EP. “If after 33 years of practice I allowed myself to be sucked into conflict so it escalated to ‘extremely disturbing’ on a regular basis,” wrote another, “I would be dead from stress.” Many were interested in finding out about additional resources and several suggested developing a formalized training program in conflict management.

EPs seem to vary significantly in the length of time needed to rebound from an emotionally disturbing interaction. While some bounce back in minutes, others remain haunted by the disturbing interaction for days to weeks. Perhaps future studies could target the subgroup of our colleagues who are “rapidly resilient” to determine if they have certain coping mechanisms or tricks that are teachable and transferable.

Many readers shared advice on how they personally deal with conflict. Some preferred intense self reflection: “We must examine and control our own emotions and interactions…The problem is that most of us have a difficult time honestly recognizing our own inefficiencies.” Others lean towards cathartic unloading: “I bitch. I talk a lot. Then I get over it.” Some prefer to resolve issues real time, not letting things, “simmer inside of you.” Still others are more comfortable regrouping after tempers have cooled down, arranging “a private moment where we can discuss our differences.” Some choose dealing with the issue head on while others are challenging their hospital administrators to act on it under the Joint Commission’s new disruptive physician requirements. Ultimately, how we deal with conflict is based on a range of individual circumstances and preferences. However, if one thing is clear, it is that we must find ways to work through conflict in a peaceful way through clear communication, not only for patient safety, but for our own sanity and career longevity.