As an emergency medicine (EM) practice management consultant I”m frequently asked “How can we determine what’s fair to pay for physician administrative duties?” It’s an emotional subject in every group because it involves the discussion of each member’s relative value to the business enterprise side of the practice.

As an emergency medicine (EM) practice management consultant I”m frequently asked “How can we determine what’s fair to pay for physician administrative duties?” It’s an emotional subject in every group because it involves the discussion of each member’s relative value to the business enterprise side of the practice.

There are three principles that should guide all group stipend discussions and three subdivisions of stipend dollar amount determination that if utilized have the potential of taking most if not all of the subjectivity out of the process of stipend formulation, review, and adjustment.

First Principles: Have Some

Administrative stipends are worse than heroin in their addictive potential; no one wants to give one up or be the heavy that has to tell a fellow partner that the group has outgrown his or her stipend. Left unaddressed, however, the natural tendency is for administrative stipends to grow, to cause their recipients to increasingly distance themselves from the group’s real business (the practice of EM), and to eventually begin to compromise the group’s competitiveness in the marketplace. In an equal ownership group even the physicians who are otherwise good businessmen tend to avoid the subject of stipend review based on the tacit understanding that threatening someone else’s stipend may ultimately threaten their own. Short of not granting a stipend in the first place the most business-like way to manage such a potentially contentious issue like stipends is to have a set of principles that guide a process that is applied equally and impersonally to all stipend decisions. Let’s begin with the three principles.

Principle #1: No physician should be paid a stipend to do anything that could be done at less cost (and perhaps better) by a non-physician.

When an EM group is small (one or two hospitals, less than a dozen partners) having some physician members of the group performing most of the practice management and administrative tasks may in fact be the most cost-effective solution. Hiring even small amounts of outside help involves orienting them to the group’s culture, explaining the group’s needs, passing information back and forth, and supervising their work product. Sometimes, even though a physician resource is more expensive (especially when paid fairly for his or her time), it is still, in the final analysis, the most cost-effective answer. But as we said above, once granted stipends are hard to reduce or eliminate as the practice grows and adds more sophisticated non-physician practice management and administrative staff.

Dedicated practice management staff often do a better job than a physician not because they are smarter but because they can devote their full time to that area, gaining cumulative experience, keeping up with the technical information flow, and attending educational meetings in their subject area that a physician doesn’t have the time to do.

Principle # 2: No stipend should be granted without simultaneously providing for at least an annual review of the associated work product, a methodology to assure objectivity in the review process, and a responsible person who will be accountable for seeing that the review and recommendations for adjustment get done by a certain date in time.

There are numerous easily obtained methodologies for conducting annual performance reviews. What’s different about the equal ownership EM group is the lack of hierarchy. No one technically reports to someone else because everyone is an equal owner. In the absence of hierarchy it is critical that the process be metrics-driven and require as little subjective input as possible. Of course no evaluation of results can possibly occur if the group hasn’t taken the time to write a job description for the position and provide a clear set of expectations and goals.

Principle # 3: No stipend dollar amount should require the physician filling that leadership role to take a cut in average hourly compensation to serve the group’s needs.

This is another issue with great potential for acrimonious debate in the independent EM group. The arguments for and against parity are legion, but here’s my rationale:

The only two things that distinguish one EM group from another are the key relationships it is able to create and maintain, and the quality and effectiveness of its leadership. The very existence of the practice depends not so much on how its members practice medicine but rather on the leadership decisions it makes.

Leadership is a unique quality unequally distributed among people in general and emergency physicians in particular. Not everyone is suited for leadership jobs. Many went into EM in part to avoid them. To be an effective leader you must have interest, aptitude, and a high level of emotional intelligence, the latter of which quality is another commodity unequally distributed among us. Therefore, capable leadership is a relatively (compared to clinical ability) scarce commodity in every group. If you doubt this just look at what happens to groups who rotate the leadership positions regardless of interest, aptitude, and ability.

Medical practice leaders cannot retain their credibility and effectiveness in the group if they don’t continue to practice EM and do it well. Moving back and forth between leadership duties and clinical practice is more stressful than most people would think. It takes an extraordinary level of time management skill to do it well.

Leaders are not made in a day. Being an effective leader requires years of study and experience. Leaders thus have to keep current with two sets of continuing education, leadership and clinical.

Some leadership roles such as managing patient or medical staff complaints and peer review involve dealing with a lot of upset people, which is typically stressful, especially when the physician doing it has had little or no training in this specialized interpersonal skill set.

Clinical shift work is time-circumscribed whereas many leadership jobs have 24/7 responsibilities.

The bottom line is that effective emergency department leadership is demanding, important, and requires skill that not everyone has, , and should not require a cut in pay for the honor of doing what most consider to be a thankless job?

How much should the leadership be paid?

There are clearly tasks that require a physician to perform.Group officers, like the President and Chief Medical Officer, must be physicians. Peer review has to be led and directed by a physician and risk and litigation management definitely require a physician’s expertise. But relatively little on the business management side of the practice requires a physician’s knowledge and training. Putting them in that role is a waste of their time and is not cost/effective.But whenever you have determined that it is essential that a physician fill a role or perform a set of tasks I recommend looking at the stipend amount as being comprised of three subdivisions, two of which are objectively quantifiable while the third is possible to determine in advance and apply equally to all stipends.

#1 Straight Hours

Hours or time involved is the first of the three subdivisions. This is theoretically easily quantifiable. Using the position job description as the starting point, add up the hours for each defined duty. No credit should be given for time spent in areas not in the job description without going through the process es

tablished for modifying it. If necessary, keep a log of activity, but the point is to arrive at an objective monthly average number of hours it takes to perform that role’s duties. This number, multiplied by the average clinical practice compensation rate, should establish the base stipend amount. If someone is suspected of padding the tab you can check attendance records or require a written summary of the meeting and what was discussed.

#2 The Hassle Factor

The only role in which the hours construct breaks down is that of the Medical Director. The nature of that job is dealing with people wandering into the ED and wanting a minute or two to discuss a problem regardless of whether it happens to be an office day or a clinical shift day. These constant interruptions erode the Medical Director’s clinical practice productivity through no fault of his own. Accordingly, many groups schedule him more during weekdays when they know people will be looking for him and they protect his productivity level so that he makes no less than the average productivity of the group.

Serving as the physician liaison for recruiting would be, for me, near the low end of hassle factor. It can be done at the physician’s convenience and has little stress associated with it. The mid-range might be represented by the physician who manages peer review and physician counseling – still easy on the schedule but a completely different level of stress when having to confront a colleague about his or her deficiencies. The group President’s job would fall near the top of the mid-range because of the job’s demanding schedule and moderate stress, but it is not a 24/7 job. The top of the range of hassle factor has to be the Medical Director’s job. This job is a 24/7 responsibility when done well and the duties consist of dealing with one upset after another while simultaneously trying to lead the department toward its declared vision.

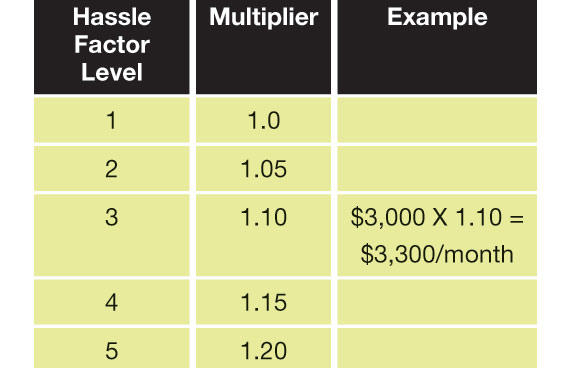

So how about establishing a scale in advance to adjust for the hassle factor, define what roles are at what level, and apply that across all stipended roles?

Combining these two subdivisions, we might have an example like a mid-level hassle factor job (say managing RM/QI) that requires 20 hours per month in a group paying an average of $150 per hour of clinical staffing. 20 X $150 = $3,000 as a monthly base stipend amount. This number would then be adjusted according to the hassle factor scale developed in advance. A typical 1-5, least to greatest, scale might be:

Every group should decide for itself what roles fall where on this scale.

#3 Results

Stipends should be tied to accomplishing objectively measurable targeted results. The group’s annual strategic planning should establish these targeted result goals and determine an objective way to measure the value to the group if the goal is accomplished. For example, let’s say the group has an ED seeing 50,000 visits per year with a LWBS rate of 6% and a cash collection per visit of $120, and the group decides that an important strategic objective is to reduce the LWBS by a third, from 6% to 4%. Knowing that the payer mix of patients who LWBS is better than the average we can assume that each patient who leaves without being seen costs the physician group at least $120. 2% of 50,000 visits is 1,000 patients. Retaining these patients would therefore be worth $120,000 to the group. Providing the Medical Director a one-time bonus incentive of 10% of the incremental dollars that retained by the group is a great way for the group to direct and focus the attention of its leadership. And while the Medical Director gets $12,000 the group gets $108,000! Some might put a minimum target level under this requiring that no bonus would be payable unless at least a 1% reduction in the LWBS is achieved for, say, one full quarter.

Making Adjustments

this subject can be so contentious in the independent EM group that it is simply impossible to deal with. In that circumstance the group may wish to consider bringing in an experienced outside consultant to evaluate the stipends being paid and make recommendations for their adjustment. The governing body can than accept or reject the recommendations in a more impersonal way.

Using hours, hassle factor, and accomplishing targeted results, along with principle-driven job descriptions and goals, annual performance reviews, and stipend amount adjustments can rationalize what is otherwise a difficult and sometimes emotional subject for the independent EM group. Imagine the time your group would have to devote to growing the practice if it could stop arguing about this subject and move on.

Ronald A. Hellstern, MD, FACEP

Principal & President, Medical Practice Productivity Consultants