Gastroenteritis, GE reflux, other? Ultrasound is a great tool for evaluating a variety of abdominal pathologies.

It’s been a long and busy winter weekend in the Pediatric ED, and you are really looking forward to leaving at the end of your shift; now less than 30 minutes away.

One of your continually cheerful residents approaches you and states, “I know you’re almost out of here, but this will be quick and easy. I just saw a six-plus week old with one day of vomiting whose grandmother has had similar symptoms. He looks great and has tolerated oral liquids without any additional vomiting. I’d like to send him home.”

Hopeful that you might actually finish your shift on time, you ponder the information provided. Excellent resident, the infant a little old for pyloric stenosis, the presence of a sick contact, etc.

With some ambivalence, you respond: “Let’s do the right thing and ultrasound him. We’ll get it done quickly, and it will be normal, and we’ll get him home with continued oral rehydration.”

After gathering the necessary paraphernalia, including a heated blanket, pacifier, oral sucrose solution and warmed ultrasound gel, you and your resident enter the room. Before you, just as your resident said, is a well-nourished and hydrated infant. His mother reiterates a history of non-bilious and non-bloody emesis, no diarrhea, full-term vaginal delivery, and no family history of pyloric stenosis. Mother’s contention that the emesis was “projectile” doesn’t do much to change your expectation of a normal study, particularly after his mother affirms the grandmother’s illness.

You ask the mother to assume a semi-recumbent position on the patient gurney with her infant on her lap in an almost supine position. You make a little baby-nest using the heated blanket and give him the pacifier doused with the sugar-flavored solution. You begin by gently palpating his abdomen, which is soft and non-tender. You do not feel a characteristic “olive” considered pathognomonic for pyloric stenosis. Applying warm gel to a high-frequency linear probe you hand it to the resident and direct her to begin scanning below and slightly caudal to the thoracic cage in a transverse-coronal orientation. Using the hepatic portal vein as a reference point, you advise her to look for the characteristic “hamburger sign” immediately medial to the gallbladder” and…

“Oh my, there it is.”

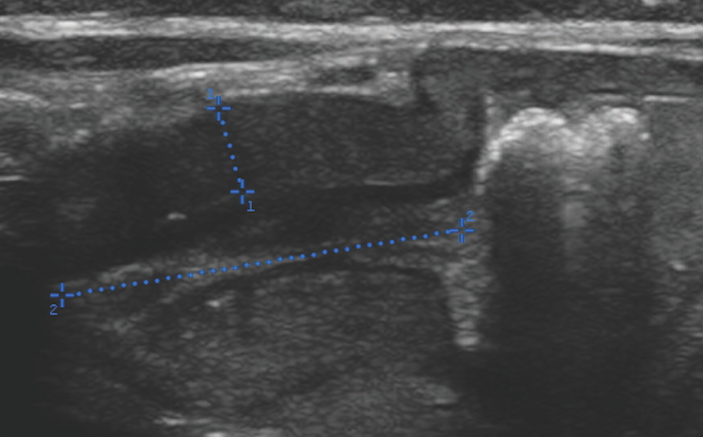

Not only did your resident “nail it” almost instantaneously upon application of probe to the abdomen, but also the image is compellingly positive. The pyloric muscle is obviously thickened and appears larger than normal (Figure 1 above). Measurements include a width of approximately four millimeters and a length of almost 20 millimeters, well beyond the norm. You observe for a few minutes and note no fluid is traversing the pyloric channel. You ask your resident to rotate the probe in order to identify the characteristic “donut sign,” noted in Figure 2 below.

The patient is admitted for overnight intravenous fluids and a surgery consult. A laparoscopic pyloromyotomy is performed the next morning and the child is discharged home that evening.

Debriefing with the resident, you wisely decide to forego any defense of your clinical judgment and emphasize how ultrasound markedly improves the sensitivity of evaluation for a variety of abdominal pathologies, including pyloric stenosis. The parents expressed gratitude that you went the “extra mile” on behalf of their child. You, however, know how close you came to not doing the study and experience tremendous relief and gratitude that this valuable technology was available. Making this diagnosis made staying late more than worth the time and effort.

Teaching Points

- Pyloric stenosis is, literally, a narrowing of the anatomic channel leading from the stomach to the duodenum. It typically presents at two to six weeks of life and has a four-fold higher prevalence in male infants. Pyloric stenosis is considerably more common in those of Caucasian ancestry and is diagnosed more often in first-born children. It is likely multifactorial in etiology, involving both genetic and environmental factors.

- The presentation is usually one of progressively worsening non-bilious emesis. The vomiting of pyloric stenosis is often described by parents as projectile, suggesting greater forcefulness than the regurgitation that occurs with infant gastroesophageal reflux. Our experience is that this description is non-specific. In addition, clinician appreciation of the characteristic palpable epigastric/right upper quadrant olive is difficult.

- Customary teaching emphasizes the potential for the development of a hypochloremic, hypokalemia metabolic alkalosis resulting from protracted vomiting, dehydration, and compensatory hyperaldosteronism. Due to the increased availability of ultrasound facilitating early diagnosis, the discovery of this metabolic abnormality occurs much less frequently than in the past.

- Ultrasound adds to the physical examination, laboratory studies and historical information and is the diagnostic test of choice for pyloric stenosis, providing for direct visualization, measurement of the pyloric muscle and assessment of transpyloric fluid movement.

- There is some disparity regarding what is considered abnormal pylorus dimensions. Two centimeters is considered to be a normal muscle width while anything above 3 centimeters is considered abnormal. Two to three centimeters is considered an equivocal muscle width and warrants a period of sonographic observation for possible trans-pyloric passage of gastrointestinal fluid. Channel length of 10 centimeters is considered normal while 14 centimeters is frequently cited as the threshold for abnormal elongation. The pyloric channel will often appear curved on long-axis view, leading to obliquity of measurement and possible indecision regarding the accuracy of assessment (Figure 3 below with Figure 4 being the short axis view). An instructive pearl for emergency department screening sonography is as follows: A normal pylorus can be made to appear abnormal, but an anatomically abnormal pylorus can never be made to appear normal. Given the likelihood of subsequent consultative pre-operative ultrasound evaluation performed by a colleague in radiology, the trend toward exam sensitivity should encourage ED physicians to act upon their positive sonographic findings. Admission and overnight intravenous fluid prior to a consultative study provides an added measure of safety.

- Although many of our pediatric emergency physicians obtain valid and accurate images, we have chosen to not bill for this particular ultrasound study as it is non-urgent and doing so would disrupt an established and functional practice algorithm. However, we have found that ED physician-performed ultrasound studies for pyloric stenosis and other abdominal conditions increase diagnostic sensitivity for atypical presentations, such as in our case report.

- Finally, it should be emphasized that an excellent clinical appearance is not incompatible with mechanical bowel obstruction in young patients who present with vomiting. Although not perfectly analogous, a pearl of wisdom — extracted from strategies utilized in the diagnosis of malrotation — is that the younger the patient, the more well-appearing, and the earlier in the course of vomiting that the emesis becomes bilious, the more likely one should be to suspect mechanical obstruction. Although pyloric stenosis is characterized by non-bilious emesis due to the site of obstruction being proximal to the Ligament of Treitz, the other tenets apply and may prevent unnecessary delay in diagnosis, as almost occurred with our patient.