It’s Monday night and you are thankful that you put on your running shoes. After a seemingly calm holiday weekend in the emergency department, you walk in to find every nook and cranny filled with weekend warriors who pushed the envelope just a little too far on their extra day off of work. You smile compassionately as you walk by the poor mom who broke her ankle skydiving for the first time, and quietly shake your head at the gurneys full of college students who are still sweating out alcohol through their sunburned bodies.

Your next patient looks like he’s had a run for his money this weekend too. Although his physique suggests that he is a rather fit and tough athlete, his hunched shoulders and hand on his upper abdomen tells you he’s experiencing more pain than he is willing to admit. He is 42 years old, otherwise healthy, and his vital signs look rather unremarkable: HR 62, BP 110/58, RR 20, O2 sat 98%, and temperature of 99.0°C. A quick interview reveals that he was out playing rugby with his old college teammates this weekend, and then suddenly felt this strange discomfort in his “stomach” this afternoon. They had been playing in a full-tackle “old boys” rugby tournament all weekend, so he initially just thought he was sore or had “torn a muscle”. He’s mildly tender in his bilateral upper quadrants and over his epigastrium, but his stoic manner is throwing off your clinical gestalt. He says it hurts every time he takes in a deep breath, but he denies any cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, or back pain.

He’s tender enough in his upper quadrants that you worry he may have suffered from some solid organ or viscous injury. Given his history, you opt to order a portable chest X-ray and a CT of his abdomen and pelvis. With the number of trauma patients in the ED right now, you know his scan is going to be delayed. After the nurses have secured a peripheral IV and obtained an iSTAT creatinine, you notice that your patient is still holding his stomach in pain and his blood pressure is a tad bit lower than before. Something just isn’t right.

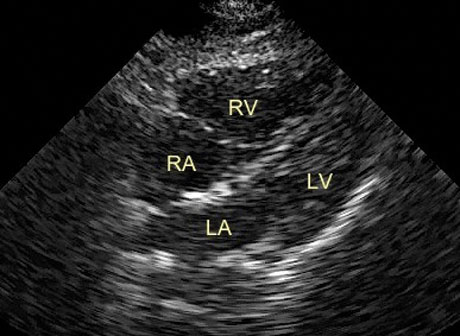

A quick bedside eFAST exam does not reveal any free fluid in the abdomen and the symptoms do not seem to be from a hemothorax or pneumothorax either. As you start prepping your probe to obtain a subxiphoid view of the heart, you can’t help but notice that he winces every time he takes in a deep breath. You obtain the following US image and silently thank the inner voice that kept you from anchoring to a snap diagnosis.

What do you see on this ultrasound image? Click HERE to read conclusion.

Given the ultrasound findings, you delve a bit more into his history. No, he doesn’t have any other pulmonary problems that could lead to RV strain. Yes, he does have some PE risk factors, like driving across the country to play in this rugby tournament, and an aunt with a history of blood clots. You opt to include a CT angio of the chest as part of his work-up and praise your inner voice once again when the radiologist calls to report that your patient has a large “saddle” pulmonary embolus and remarks how happy she is that they hadn’t scanned his abdomen and pelvis with contrast before you added on the chest CT. With the patient safely admitted, the vascular surgeon comes up and remarks how lucky that patient was to have the physiologic reserve to handle such a large PE. The internist states how lucky he was to have no injuries precluding him from receiving anticoagulation. Your nurse remarks how lucky you are to have made the right diagnosis. You simply push your ultrasound machine down the hall and answer in a humble voice, “Sometimes it’s just better to be lucky than good…”, but deep down, given the atypical presentation including a pulse rate of 62, you know that your patient’s real stroke of luck today was having you as his doctor.