Suppose you get stopped in the hallway outside the ED by a colleague who “has a friend” who went to Las Vegas and, about a week later, developed genital ulcers. He wants your advice regarding what to tell his “friend” to do. What do you tell them?

Sexually Transmitted Infections, Part 1: Ulcer Issues

Suppose you get stopped in the hallway outside the ED by a colleague who “has a friend” who went to Las Vegas and, about a week later, developed genital ulcers. He wants your advice regarding what to tell his “friend” to do. What do you tell them?

Your colleague’s “friend” is not alone. There are 20 million cases of sexually transmitted infections annually in the United States. In general, the incidence had fallen in recent years, but that trend recently reversed and these diseases are slowly resurging. As a good proportion of these patients present to the emergency department for care, emergency physicians need to be familiar with how these infections can present, how to test for them and how these patients should be treated.

To start, sexually transmitted infections can be broadly divided into those that cause lesions, with or without adenopathy, and those that present primarily with nonulcerative symptoms, frequently including a genital discharge. The sexually transmitted diseases that cause lesions in the United States are herpes genitalis – the most common – followed by syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum and chancroid. Chancroid is, however, extremely rare in North America. The infections that tend to present with discharge are chlamydia, gonorrhea and pelvic inflammatory disease. Frequently, patients may have more than one infection at a time, meaning that testing for other sexually transmitted infections is often indicated (and is recommended by the CDC).

Consider three similar patients:

——————-

A 30-year-old female, complains of a recent viral illness characterized by low grade fever and myalgias who comes to the ED because she developed multiple painful genital lesions and dysuria without urgency or frequency. Her pelvic exam shows genital lesions that are shallow and very painful and she has bilateral, mildly tender, nonfluctuant lymph nodes.

——————-

A 26-year-old male concerned because he noted an ulcer on his glans while urinating today. His examination shows a single, painless ulcer on the glans of his penis and he has several firm, rubbery bilateral lymph nodes.

——————-

A 24-year-old male presenting with multiple, painful lesions on his penis and right groin pain. Examination shows several irregularly-bordered, purulent-based painful ulcerations on the shaft of his penis and he has a 5 cm, tender, erythematous, fluctuant right inguinal lymph node.

——————-

Can you tell which organism is most likely in each patient?

A good history and physical examination often provides most of the information necessary to strongly suggest the infecting organism. History should include questioning about sexual partners and practices, a history of sexually transmitted infections and a menstrual history in women. Patients should be questioned about recent illnesses and skin and joint complaints. Your examination should include vital signs, skin and lymph node exam, joint exam and a genital examination including a speculum and bimanual examination in women.

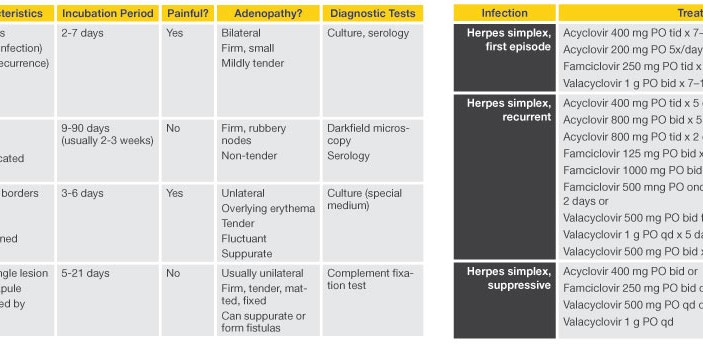

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics for each of the most common ulcerating sexually transmitted infections in the United States.

The most common ulcerating sexually transmitted infection in the United States is herpes genitalis. Serologic testing shows one in five adults you pass during your day have been infected with the virus. In herpes virus-naïve patients (e.g. those without previous infection, including those who do not have cold sores, or herpes labialis), initial acquisition of infection with the virus causes a systemic response within 2-7 days of exposure. Initially, patients develop a viremia and become systemically ill, with accompanying myalgias, headache, fatigue and low-grade fevers. These symptoms last about a week, during which the patient will develop genital vesicles that rapidly ulcerate, leaving multiple painful ulcers that may coalesce, particularly in women. Bilateral, mildly tender, nonfluctuant adenopathy develops during the second or third week. It takes a total of 2-4 weeks for the lesions to heal completely. Patients who have a history of herpes labialis (and therefore antibodies to one serotype of herpes) who acquire herpes genitalis have a much less severe syndrome, often only developing local, less severe genital symptoms.

Genital herpes infections are not eradicated but become latent, and the virus settles in the sacral plexus. As a result, recurrences in the first year after infection occur in 60-90% of patients and can continue for many years. These recurrences are often heralded by paresthesias in the genital region followed by several vesicles that ulcerate. Healing is usually complete within a couple of days to a week.

While the diagnosis of herpes is often made clinically, confirmatory testing should be strongly considered. This testing is particularly important in women of childbearing age, as surveillance during later pregnancies is crucial to prevent congenital and intrapartum infection of the baby. This confirmation testing can be done using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or serologic testing.

Treatment for genital herpes is with antiviral drugs (see Table 2). Route, dose, and duration depend on whether the infection is primary, a recurrence or for suppressive therapy.

So, to return to our three case examples (inset) our 30-year-old female with the recent viral illness and genital ulcers has primary genital herpes. In contrast, the 26-year-old male with the painless genital ulcer is sporting a typical case of primary syphilis. This patient acquired the spirochete Treponema pallidum during a sexual encounter 4 weeks ago, a typical incubation period for the infection. His chancre is painless, solitary, indurated and clean-based, he is not systemically ill and adenopathy is not a prominent finding. If he had not sought medical attention, his chancre would have disappeared, but 2-10 weeks later, he would have developed a papulosquamous rash on his trunk that likely would have involved the palms and soles. He may also have developed flat lesions on his tongue called mucus patches, diffuse shotty adenopathy and flat lesions on the genitalia called condyloma lata. If he did not see a medical practitioner during that secondary stage and received treatment, his symptoms would have resolved, but his infection with the spirochete would have become latent for as long as a decade. At that point tertiary signs would have begun to manifest, predominantly involving the cardiovascular and central nervous systems (e.g. aortic aneurysms, gummas, peripheral neuropathy).

While primary and secondary syphilitic lesions can be diagnosed with darkfield microscopy, this method is often not available. Syphilis is diagnosed by serology, using the rapid plasma regain (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests. The titers of these antibodies can follow response to therapy, but as these tests are not specific to the spirochete, positive RPR or VDRL test may be confirmed with serologic tests specific to the spirochete (the MHA-TP and FTA-ABS) tests.

Penicillin treats all stages of syphilis, but dosing varies based on stage. Primary, secondary or early latent syphilis is treated with benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units intramuscularly in a single dose. Late latent syphilis is treated with the same dose but repeated for three doses, 1 week apart.

So, what does our 24-year-old with the painful genital lesions and large, fluctuant lymph node have? The lesions suggest herpes, but they are deeper than expected for herpes, the patient has no systemic symptoms, and he does not have the mild lymphadenopathy expected with the infection but rather has a large, fluctuant lymph node. This patient is presenting with symptoms classic for chancroid. Caused by Haemophylis ducreyi, a fastidious gram-negative bacterium. This infection is extremely rare in the United States and, when seen, occurs in small, localized outbreaks. Incubation is usually less than one week, and symptoms begin with a papule that rapidly ulcerates and multiple, painful ulcers with purulent bases appear. Half of patients develop a unilateral, large, painful, fluctuant lymph node that may spontaneously drain. In the half of patients who do not develop the bubo, this infection can be difficult to differentiate from the more common herpes genitalis.

Diagnosing chancroid is challenging, as there are no nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of the organism, and it is very difficult to grow in typical culture media. The presence of a bubo is highly suggestive of the diagnosis.

To treat chancroid, any of the following four curative regimens may be used: a single dose of azithromycin 1 g orally; a single dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg IM; ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally twice daily for 3 days; and erythromycin base 500 mg PO three times daily for 7 days. Bubos usually respond to antibiotic therapy and incision and drainage is not recommended. If the node needs urgent drainage, needle aspiration is usually adequate.

While each of our patients had a different infection, each could be co-infected with other sexually transmitted organisms that cause ulcers, with those that do not cause ulcers, with hepatitis B or with HIV. All patients with a sexually transmitted infection should be broadly tested for STIs and HIV.