When should you have a high index of suspicion for cardiac tamponade?

You are working in the emergency department when you see a 52-year-old female present with several days of dyspnea and fatigue. She states that over the past few days she has felt increasingly short of breath in her daily activities, and today became short of breath even with rest. She notes that one week ago she had an aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis. After the surgery she initially felt better. In addition to the recent surgery she has a history of smoking, coronary artery disease and hypertension. On review of system denies chest pain, cough, fevers and palpitations.

On physical exam, she is resting comfortably in bed. Her temperature is 98.6°F, blood pressure is 127/94, heart rate is 102 beats per minute, she is breathing 18 times a minute, with a pulse oximetry of 97% on room air. Heart and breath sounds are slightly distant, but otherwise normal. You do not appreciate jugular venous pulsations, but note 1+ symmetric lower extremity pitting edema. EKG is notable only for sinus tachycardia.

You start your workup with a chest x-ray, basic labs, d-dimer, and cardiac biomarkers. Lung fields are clear on chest radiograph, and her d-dimer returns slightly elevated with otherwise normal labs. You quickly add on a CT chest after updating the patient, and move on to see another patient.

While awaiting CT your patient’s nurse comes to find you concerned that the patient now has mild confusion and hypotension. You return to her bedside to see that her blood pressure and heart rate are 82/58 and 123, respectively. You ask the nurse to pressure bag in a liter of fluids, and you perform a bedside cardiac ultrasound. The ultrasound shows a moderate sized pericardial effusion with right ventricular free wall diastolic collapse, a hyperdynamic left ventricle and a plethoric IVC.

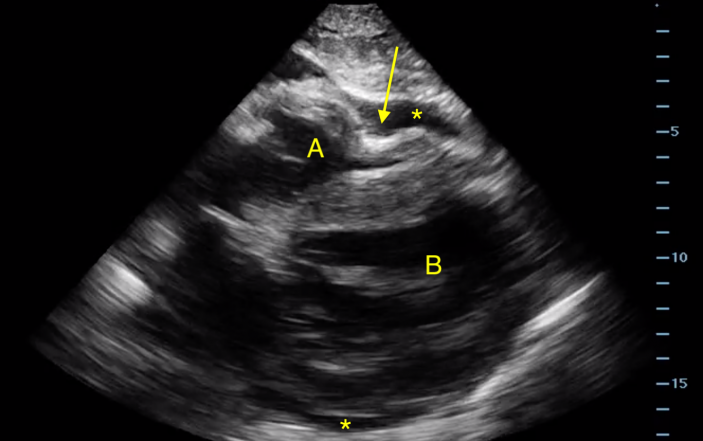

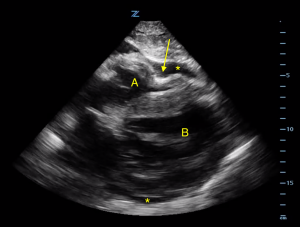

- Parasternal long axis view of the heart. The right ventricle (A) is closest to the anterior chest (top of screen), and the thicker walled left ventricle (B) is more posterior. A pericardial effusion (*) is seen surrounding the heart. The arrow points to the paradoxical motion of the right ventricular free wall seen in cardiac tamponade.

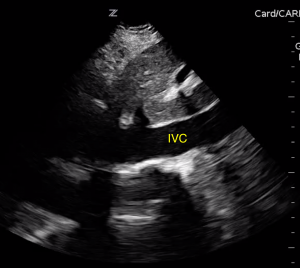

- Long axis view of a plethoric IVC.

Given the clinical picture and supportive findings on ultrasound, you make a diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. Your patient’s blood pressure and heart rate normalize after the fluids so you activate the cath lab for immediate pericardiocentesis.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Tamponade physiology occurs when increased pericardial pressure impairs right heart filling, this then causes reduced left ventricular preload and cardiac output.

- Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for cardiac tamponade in patients with chest trauma, pericarditis, cancer, recent myocardial infarction and recent interventions (for example central line placement, heart surgery).

- Classic physical exam findings of friction rub, muffled heart sounds and jugular venous distension are not sensitive enough to rule out the diagnosis.

Ultrasound is the primary imaging modality for cardiac tamponade, as one can identify not only a pericardial effusion, but also evidence of hemodynamic compromise including:

- Impaired right atrial and right ventricular filling with paradoxical free wall motion. This is seen as systolic collapse of the right atrium, which is an early finding, and diastolic collapse of the right ventricle which is a highly specific finding. See Image 1.

- A plethoric IVC with minimal respiratory variation from elevated right heart pressures. See Image 2.

Long axis view of a plethoric IVC.

- Pericardial and adjacent pleural fluid can appear similar on ultrasound. By examining the relationship of the fluid to the descending thoracic aorta, pericardial effusion (between heart and aorta) can be readily differentiated from an adjacent pleural effusion (posterior to aorta) on the parasternal long-axis view. See Image 3.

Parasternal long axis view of the heart. Again we see the right (A) and left (B) ventricles and a pericardial effusion (*) surrounding the heart. The arrow points to the descending thoracic aorta which serves as a landmark to differentiate pericardial versus pleural effusion.

- A more advanced ultrasound technique includes evaluating for valvular pulsus paradoxus. This is done by assessing pulse wave Doppler inflow velocities through the mitral valve. Mitral inflow velocity is measured in an apical four-chamber view by placing the pulse wave Doppler gate just distal to the mitral valve in the left ventricle. Peak velocities are measured during inspiration and expiration. Variation in velocities >25% from expiration to inspiration is abnormal and seen with tamponade physiology.

- While tamponade is ultimately a clinical diagnosis, the above ultrasonographic findings are helpful in identifying subclinical tamponade.

Supplemental video: Cardiac tamponade. Note the pericardial effusion and right ventricular diastolic collapse.