The United States is a capitalist country in which entrepreneurs who see opportunities and are willing to take some risks can generally do well. Finding the opportunities is the hardest part of the equation. One wide open market that would seem to be a slam-dunk opportunity is that of health clinics in retail stores.

Are retail clinics eroding our business or are they the next step toward cost containment?

The United States is a capitalist country in which entrepreneurs who see opportunities and are willing to take some risks can generally do well. Finding the opportunities is the hardest part of the equation. One wide open market that would seem to be a slam-dunk opportunity is that of health clinics in retail stores. The concept seems compelling for several reasons. They are instantly credible because of the mega-businesses they are associated with (Wal-Mart, K-Mart, major grocery chains). They don’t require high cost physicians to provide the care – nurse practitioners can practice independently in 11 states and in 27 states are only required to practice “in collaboration” with a physician. Add to that the fact that primary care and emergency medicine are typically associated with long waits and high costs – two things absent in retail health clinics – and the case seems to slam shut.

As a reflection of the huge disparity in costs (not charges) for acute care in various settings, using a large insurance company database, Mehrotra, et al found that the costs for care for episodes of otitis media, pharyngitis and UTIs averaged $110 in retail clinics, $160 in physicians’ offices and urgent care clinics and $570 in hospital emergency departments. Think quality was at least part of the reason for the higher ED charges? Probably not. On 14 quality measures, compliance at the retail clinics, physicians’ offices and urgent care centers averaged between 61-64%, compared to only 55% in the EDs.

click to enlarge

As the antithesis of the “medical home” concept that is being touted by primary care physicians, and a likely arch-enemy of most EDs’ fast track care, these retail-based clinics could potentially present a competitive threat. However, some of the mega-retailers are not taking an “in your face” approach. They are partnering with local hospitals and co-branding the clinics with them. In February, 2008, Wal-Mart announced they would co-brand in-store clinics in Atlanta, Little Rock and Dallas under the name “The Clinic at Wal-Mart,” presumably in an effort to brand the service as on outside provider in Wal-Mart space. The espoused goal of the program is to open 400 such clinics by 2010.

Do mega-retailers like Wal-Mart have the clout to substantially change the face of U.S. health care? To a certain extent, Wal-Mart already has with their $4 prescription program. Now every major prescription outlet has a similar program. With millions of customers in their stores every day, the appeal of fast, convenient, one-stop, quality care at a low cost is unqestionable. And there are some benefits that don’t exist in a family doctor’s office – the use of a system-wide electronic medical record to rapidly access prior information, consistently applied medical protocols, extended evening and weekend hours, lower costs and, importantly, someone to complain to if the wait is too long or the receptionist is curt – the store manager.

Despite all this, in December, 2008, the Commonwealth Fund released an “issue brief” suggesting that maybe this “can’t miss” opportunity was having some challenges.

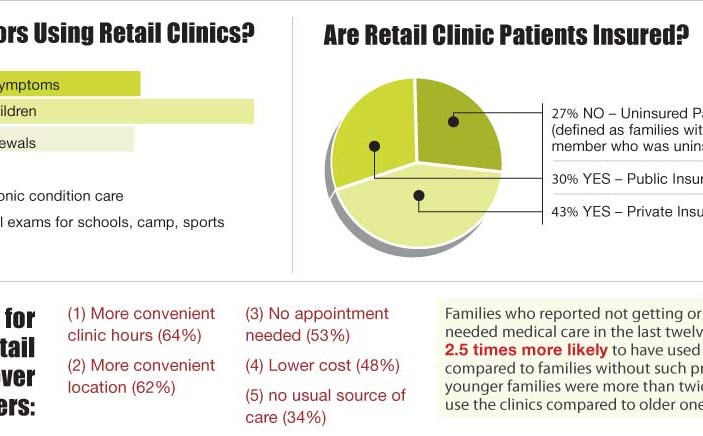

The report noted that, despite the fact that the clinics were used disproportionately by younger families and those having difficulty accessing health care services (including the uninsured and minorities), in 2007 only 1.2% of U.S. families (1.7 million) reported that they had visited a retail clinic during the past twelve months and only 2.3% reported ever having visited one according to a study performed by the Center. The authors contend that the boom in the growth of these clinics has slowed and this will disproportionately affect underserved Americans who lack affordable alternatives to primary care.

More specifically, they note that there were only 60 such clinics in 18 states at the beginning of 2006, about 900 clinics in 30 states by the end of 2007 and by mid-2008 there were approximately 1,100 (as of July 2008, Florida had the most clinics – about 135). However, these retail-based clinics are a new phenomenon and many have not been open long enough to meaningfully contribute to the user base. For example, the first retail-based clinics were established in a grocery store chain in Minnesota. There, 6.4% of the state population (191,000 Minnesota families) reported ever using a retail clinic and 4.4% used one during the past year.

Another study by Mehrotra, a much brighter picture is portrayed. It is noted in the introduction that these clinics are estimated to grow to almost 6,000 in number in the next five years (another estimate is that 6,000 clinics will be in place by 2011 and that they will see more than 50 million visits per year), and recent polls suggest that 15% of children and 19% of adults are very likely or likely to use a retail clinic in the near future.

Predictably, these clinics are under attack by traditional medicine. The authors report that the AMA, the AAFP and the AAP have raised concerns about whether health professionals operating at these sites make accurate diagnoses and appropriate triage decisions, and whether retail clinics potentially disrupt existing physician-patient relationships. This study attempted to address the demographics of who is using these clinics and the reasons for their use as compared to primary care offices and emergency departments.

But a more fundamental question exists. Are retail clinics providing needed care? With two-thirds of their diagnoses being viral conditions or conditions in which antibiotics help the minority of patients, the question remains “Is the care provided really necessary or is it just an increased cost to the patient / insurer?” Moreover, given the high percentage of infectious illnesses that are diagnosed, is it likely that there will simply be an increase in unneeded, and possibly contraindicated, antibiotics.

W. Richard Bukata, MD

Dr. Bukata is a clinical professor at LA County / USC Medical Center, the ED medical director at the San Gabriel Valley Medical Center, the president of The Center for Medical Education, Inc., and the founder and medical editor of Emergency Medical Abstracts

1 Comment

“This study attempted to address the demographics of who is using these clinics and the reasons for their use as compared to primary care offices and emergency departments.” Isn’t that the purpose of these clinics – to keep people out of the ER so the really sick people can get the urgent care that they need? This study is just another attempt to attack NP’s and the quality care that we provide. I’m tired of MD’s and their false accusations/assertions.