Like haldol, only better.

When someone mentions droperidol (Inapsine®), the drug seems to incite very different reactions. Some seem to remember it fondly as an effective drug for rapidly sedating severely agitated patients or as a powerful antiemetic. Others murmur about the potential for the drug to induce torsades de pointes (TdP).

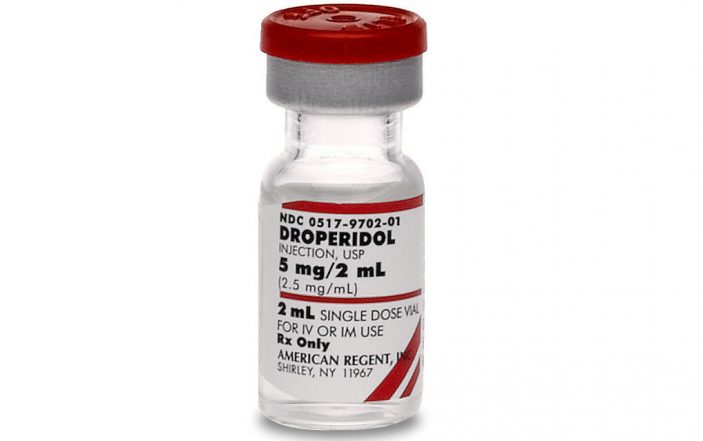

Droperidol is used in Emergency Departments across the world for multiple off-label indications including, but not limited to: nausea and vomiting, rapid tranquilization and migraine headaches. Before its removal from European markets, and the FDA Black Box Warning for QTc prolongation in 2001, droperidol was one of the most commonly used antiemetics.[1] For many years in the US, it has remained on backorder drug lists, making it hard to obtain until 2019 when American Regent reintroduced droperidol injection back into the US market.

Jack of all trades, master of none?

Since droperidol has reappeared as quickly as it left us several years ago, many younger providers with little or no experience with the drug have asked how it can be such a jack of all trades. A lot of it comes down to its mechanism of action. Droperidol, a butyrophenone similar to haloperidol, was approved in the US in the 1970s for postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), although it was originally studied as an alternative pain medication.2 Droperidol is a potent antagonist at the dopamine 2 (D2) receptor, with minor activity at the α1 receptor.

The D2 receptor antagonism makes droperidol an effective antipsychotic and antiemetic agent. It also produces significant sedation and tranquilization, which in part may be due to its similar structure to GABA.[3] The onset of effect for droperidol is less than 10 minutes, and it reaches maximum effect within 30 minutes. Its duration of effect is two to four hours, but it can last as long as 12 hours.[2] These various effects and rapid onset allow for droperidol to be useful for multiple ED patient indications.

Back to the basics

Original FDA approval was granted for PONV, but droperidol has gained wider spread use as an antiemetic in several other specialties and disease states. Droperidol is comparable or more effective than other commonly used antiemetics in the ED, such as ondansetron, metoclopramide and prochlorperazine.[4,5] In a 2015 Cochrane analysis of antiemetics in the ED, droperidol was the only drug that showed statistical improvement in the visual analog scale (VAS) at 30 minutes compared to placebo.[6] The usual dosing range for nausea and vomiting in the ED is 0.625 to 1.25 mg IV or IM. Both doses have been found to be effective, but the 1.25 mg dose may result in increased side effects, specifically akathisia.[7]

Droperidol has similar or improved efficacy to other dopamine antagonists for the treatment of migraine in the ED. In one study, patients treated with droperidol had a greater improvement in visual analog scale compared to prochlorperazine, a migraine cocktail staple.[8] The usual droperidol dose for migraines cited in literature or in practice is 2.5 mg IM or 1.25 mg IV. Adverse effects appear to be similar between prochlorperazine with no reports of cardiac adverse effects in this population.

Another common use of droperidol is the management of the acutely agitated patient. The dosing range for agitation is 2.5-10 mg IM, with 5 mg IM being most common. Droperidol offers a quick onset of action, and compared to other agents for rapid tranquilization, requires fewer rescue doses.[9,10] Adverse effects appear comparable to the other agents used for this same indication.

Too good to be true?

Overall, adverse effects of droperidol are similar to other first-generation antipsychotics including: extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), hypotension, sedation and QTc prolongation. Butyrophenone antipsychotics have less anticholinergic and antihistamine effects than other antipsychotics, but this may result in an increased rate of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).[11]

Akathisia is one of the EPS side effects more commonly associated with droperidol. The incidence of akathisia is usually comparable to other antipsychotics, such as haloperidol or prochlorperazine, in comparator trials. However, some studies do report a higher, dose-dependent incidence of akathisia with droperidol.[4,7] Another more common side effect associated with droperidol is hypotension, which is due to the antagonism of the α1 receptors. Patients receiving droperidol may experience more sedation, and the duration can be prolonged in some patients (upwards of 12 hours).[2,8,12]

Thus far, the side effects associated with droperidol are something to consider prior to use, but do not appear to be a game changer. The bigger question many providers have related to the adverse effects of droperidol is, “What about QTc prolongation and TdP?” This is the primary adverse event that led to the FDA placing the black box warning and its removal from other markets.

In addition to cases reported to the FDA MedWatch system, the FDA cited two studies for its decision to add the droperidol black box warning.13 When evaluating these literature and case reports, it’s important to note that the droperidol doses used were significantly higher than the typical doses used for nausea, migraines and even acute agitation. Lischke and colleagues were evaluating doses starting at 0.1 mg/kg, and reported significant QTc prolongation for all three of their dosing groups (0.1, 0.175, and 2.5 mg/kg), with the higher dose producing the most prolongation.[14] While there was a change from the baseline QTc in their study, there were no reports of dysrhythmias or QTc > 500 ms.

Let’s consider an average sized 70-kg patient. The weight-based dosing for the typical IV droperidol dosing range for ED indications of 0.625 – 5 mg would be equivalent to 0.009 mg/kg – .07 mg/kg, which is significantly lower.

Since 2001, there have been numerous trials and review articles published that challenge the FDA’s warning statements. The American Academy of Emergency Medicine released a safety statement in 2014 on droperidol stating that doses equal to 10 mg IM or less were safe, and doses under 2.5 mg IM or IV did not require routine telemetry monitoring that is referenced in the black box warning.[13] Gaw and colleagues completed a six-year review of all droperidol use in the Mayo Clinic ED.

They included 5,784 patients and found no deaths or dysrhythmias attributable to droperidol.[1] Of the patients selected for chart review, the median dose of droperidol was 0.625 mg; however, 40.5% of patients received doses ≥2.5 mg. Only 1% of patients who had a normal baseline EKG had a change in their QTc within 24 hours from droperidol administration. And to put this in perspective, droperidol has similar effects on QTc length as recommended alternatives, such as haloperidol and ondansetron.

The Bottom Line

Overall, droperidol is an effective medication for various indications in the ED and we should not stop using it just because it is associated with a black box warning. Upon further investigation, the adverse effects appear comparable to other alternative agents, and when used at appropriate doses, it can maintain efficacy with minimal cardiac effects.

Also, remembering to review the patient’s past medical history for prolonged QTc and other medications that can prolong the QTc are equally important when considering the risk and benefits of ordering droperidol. Overall, using the lowest effective dose and being aware of other patient-specific factors that may lead to cardiac adverse effects are important when selecting droperidol.

References:

- Gaw CM, Cabrera D, Bellolio F, et al. (2019). Effectiveness and safety of droperidol in a Untied States emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. Advanced online publication. www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem.

- Droperidol [package insert]. Shirley, NY: American Regent, Inc: 2009.

- Heyer EJ, Flood P. Droperidol suppresses spontaneous electrical activity in neurons cultured from ventral midbrain implications for neuroleptanesthesia. Brain Research. 2000;863:20-4.

- Braude D, Soliz T, Crandall C, et al. Antiemetics in the ED: a randomized controlled trial comparing 3 common agents. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:177-82.

- Meek R, Mee MJ, Egerton-Warburton D, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of droperidol and ondansetron for adult emergency department patients with nausea. Acad Emerg Med. 20019;26:867-77.

- Furyk JS, Meek RA, Egerton-Warburton D. Drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in the emergency department setting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015, Issue 9. Art No: CD010106.

- Charton A, Greib N, Ruimy A, et al. Incidence of akathisia after postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis with droperidol and ondansetron in outpatient surgery: a multicentre controlled ranomised trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35(12):966-71.

- Miner JR, Fish SJ, Smth SW, Biros MH. Droperidol vs prochlorperazine for benign headaches in the emergency depeartment. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(9):873-9.

- Martel M, Sterzinger A, Miner J, et al. Management of acute undifferentiated agitation in the emergency department: a randomized double-clind trial of droperidol, ziprasidone, and midazolam. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(12):1167-72.

- Klein LR, Driver BE, Horton G, et al. Rescue sedation when treating acute agitation in the emergency department with intramuscular antipsychotics. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(5):484-90.

- Richards JR, Schneir AB. Droperdidol in the emergency department: is is safe? J Emerg Med. 2003;24(4):441-7.

- Weaver CS, Jones JB, Chishol C, et al. Droperidol vs prochlorperazine for the treatment of acute headache. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(2):145-50.

- Perkins J, Ho JD, Vike GM, DeMers G. American academy of emergency medicine position statement: safety of droperidol use in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2004;49(1):91-7.

- Lischke V, Behne M, Doelken P, et al. Droperidol causes a dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:983-6.

Photo Credit: American Regent.com