With cure rates as high as 95% and few side effects, the new direct-acting antivirals for HCV are a life changing breakthrough for many patients.

In the last five years, there has been a revolution in the treatment of hepatitisC infections with the advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). Curerates for chronic hepatitis C are now around 95%, and the medications, while carrying a hefty price tag, have few side effects. Emergency physicians should be aware of the treatment options in order to help counsel patients who have HCV that do not have primary care access in order to help link them to potentially curative treatment.

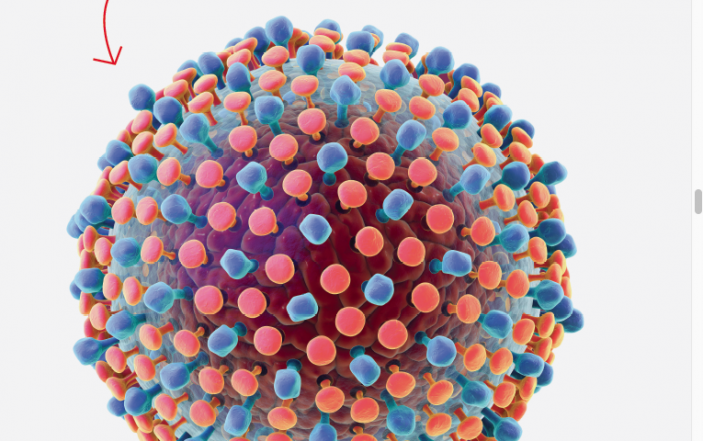

Chronic hepatitis C is the leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplants. About 2.5-4.7 million people in the United States are currently infected. Infection occurs most often through IV drug use and high risk or traumatic sexual contact. There are six genotypes, and the most common in the U.S. are types 1,2, and 3. 80% of acute infections progress to chronic HCV infections, while 20% resolve on their own. In 2007, the U.S. mortality from HCV overtook HIV, and the healthcare cost burden is over $6.5 billion in the U.S. alone.

TREATMENT

Prior to 2012, the mainstay of treatment was interferon and ribavirin, which had cure rates around 45%-80%, depending on the genotype. Treatment with these agents is more effective within the first six months of infection, but limited by prolonged treatment courses of 24-48 weeks and significant side effects. Ribavirin carries a black box warning for its teratogenic and embryocidal effects. Pegylated interferon has both antiviral and immunomodulatory effects, but can cause neuropsychiatric symptoms, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, fatigue, and flu-like symptoms.

The side effects lead to high rates of treatment cessation. In 2011, beceprevir and telaprevir (viral protease inhibitors) were approved by the U.S. FDA for use in combination with interferon and ribavirin. In the intervening years, multiple other DAAs for hepatitis C have made their way to the market. DAAs inhibit nonstructural HCV proteins and are indicated to treat chronic hepatitis C infections. Currently, treatments are available for genotypes 1-6, with cure rates around 95%. The goal of treatment is to reduce mortality and liver-related complications.

In 2014, the first interferon-free ribarvirin-free combination regimen was approved, containing ledipasvir and sofosbuvir (Harvoni). In 2016, Epclusa was released, which treats genotypes 1-6. As of 2016, Harvoni (for genotypes 1, 4, 5,and 6), and Viekira ak (for genotype 1) were the most common HCV medications prescribed. A sustained viral response to treatment (i.e., a cure) is more likely in patients under 40-45, those with less fibrosis/cirrhosis, those with genotypes 2 or 3, patients with normal insulin sensitivity, and lower viral load. However, all patients with chronic HCV infection should be considered for treatment.

SCREENING

In 2013, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommended HCV screening for everyone in the U.S. born between 1945 and 1965. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases also recommends annual screening for high risk patients, specifically IV drug users, and HIV-infected men who have unprotected sex with men.

TREATMENT DECISIONS

It is important to be aware of the treatment options in order to refer patients for care. Treatment is currently recommended for all patients with chronic HCV infection, unless they have a life expectancy of less than a year due to non-liver-related medical problems. A 12-week treatment course with DAAs costs around $90,000-$150,000, depending on medications and genotype. Because of the cost, some state Medicaid programs and insurance companies restrict treatment to patients with mid- to late-stage disease.

The decision to treat is based on the degree of liver fibrosis, as well as prior treatments, other co-infections,and co-morbidities. However, from the ED, we see many HCV patients who may not have a primary care physician and regular access to care. In patients in whom we diagnose HCV or who have known HCV, we can play a pivotal role by helping bridge their access gaps to a primary care physician through referrals, case management, or provision of information about free clinics where they can begin the process of evaluation for treatment.

SIDE EFFECTS

Fortunately, unlike prior treatments for hepatitis C, the DAAs are generally very well tolerated. In very rare cases, fulminant liver disease can develop from re-activation of hepatitis B virus. Patients on treatment are followed with approximately monthly labs to monitor for decompensation of cirrhosis or worsening kidney failure.

TREATMENT OF OCCUPATIONAL INJURIES

As healthcare workers, we are at risk for occupational exposures from needle or scalpel injuries. Needlesticks with sharps contaminated with blood from infected patients carry about a 1.8% conversion rate for HCV. None of the DAAs are approved for post-exposures prophylaxis use. However, if a health-care provider does contract HCV following an exposure, the above treatments are available.

SUMMARY

It is remarkable to watch a cure for a previously chronic and largely incurable disease move from the realm of fiction to reality. With cure rates as high as 95%, and few side effects, the new DAAs for HCV are a life-changing breakthrough for many patients. Currently, all patients with chronic HCV should be referred for evaluation for curative treatment to reduce mortality and liver-related complications.

There are still insurance barriers and limits for treatment because of the substantial cost. However, cost-effectiveness studies suggest that from a societal standpoint in the U.S. and Europe that treatment with DAAs to cure hepatitis is cost effective at any stage of fibrosis.